23 Jul Books: Writing the West (Winter 2010)

Blindsided

After a quick read of the flap copy of Blindsided: Surviving a Grizzly Attack and Still Loving the Great Bear (St. Martin’s Press; $25.99), one could be excused for thinking that the author, Jim Cole, is a bit off the beam. After all, how very few people have been mauled not once but twice by grizzly bears and still pursue their passion of getting up-close-and-personal with them while photographing the creatures in their native habitat?

Here is a man who, by his own admission in the book’s introduction, has “… hiked over 27,000 miles in grizzly country from Wyoming to Alaska.” He has traveled to 11 different grizzly ecosystems, has observed grizzlies in 10 different months and has seen fresh grizzly tracks every month of the year.

“What drives me to go back into the wild to track the great bear after nearly losing my life to it twice? It’s the hope that enhanced awareness will bring a new era of hope for greater conservation. I always want to be hopeful. … What I do is something that rises from the deepest part of who and what I am. It is who and what I am.”

It is this dedication that is most impressive, especially after his second mauling, a near-death experience in 2007 on which most of the book’s narrative is predicated. Following the severe mauling, he didn’t stop for long: “I had one of my best field seasons in 2008, especially given my age and limitations. I did everything that year I would normally do, including hiking over 2,300 backcountry miles.”

The writing does its job in carrying the reader along in an engaging fashion, but it’s the tale itself, offered in an intentionally disjointed chronological order that keeps the reader turning the pages. As with most readers, I admit I wanted to know the nittiest, grittiest aspects of his attack and subsequent recovery. And I was given all that, mixed with healthy amounts of grizzly facts, figures and history, as well as Cole’s well-reasoned pleas for increased conservation efforts involving the bruins.

His arguments in favor of tolerance and mutual respect between humans and grizzlies won’t fall on many deaf ears, though it will always be a difficult sell. Largely because, despite the best efforts of people like Jim Cole, the media will no doubt continue to worry the topic until it’s threadbare. If it bleeds, it leads. Hopefully, in Cole’s case, that phrase will take on new meaning.

Junkyard Dogs

Craig Johnson’s latest mystery, Junkyard Dogs (Viking; $25.95), pulled me in before I even cracked the cover. I’ve always been especially fond of mysteries set in winter in frigid locales, and since I was already familiar with the previous five tales in Craig Johnson’s series starring Walt Longmire, sheriff of Wyoming’s Absaroka County, I gladly jumped into his frigid snowscape with both Sorels kicking.

As with previous books in the series, Johnson seems to enjoy inflicting woes on his characters. In this book alone there are multiple clunks to heads, falling and ramming vehicles, gunshots, dog maulings and a memorable mishap involving bear spray. Other afflictions are no less insidious — a deputy’s post-traumatic stress disorder, all manner of affairs of the heart. Toss in a few small-time crooks and a handful of murders, and poor Walt is going to need the Jaws of Life to extricate himself from this book.

All this tough luck might make some folks sullen, but Longmire’s hard-knocks humility and weary, wry humor pops up often enough to keep readers nodding their heads and chuckling. Consider this, from page 88: “ … I was starting to feel like a baby seal in a Louisville Slugger factory.” And on page 277: “She studied me as if I were a variety of moron she’d never met before.”

Walt Longmire is far from the person we’d all like to be — heaven knows I’d not want his headaches or his woeful past — but there is a bit of Walt Longmire in all of us. And that’s one of this series’ simple strengths: Johnson taps into aspects of human nature we can all relate to. He knows that it’s honest-to-god, warts-and-all people, their interactions with each other and the natural world, their foibles, their fears and their humor, intended and not, and the haunting memories of loss and subsequent grief so deep it will never go away, that form the core of a good story.

Fur, Fortune, and Empire

Fur, Fortune, and Empire: The Epic History of the Fur Trade in America (WW Norton & Co.; $29.95), by Eric Jay Dolin, is the latest book in a long line of histories covering various aspects of the fur trade in North America. And to my mind, as a keen amateur historian of the mountain man era, it is one of the best. This one-volume history of a fascinating and largely vanished industry, is highly readable and all-encompassing without ever bogging in tedium. And it is further enhanced by ample illustrations, vintage photographs and paintings, a good end-paper map, a fine index, 90 pages of exhaustive end notes, and a solid select bibliography (useful for anyone interested in further exploration of the topic).

In his introduction, Dolin unabashedly explains that while numerous books and articles have been written on the American fur trade, he chose to keep his scope broad in an effort to explain “… the extraordinary story of the fur trade of old, when the rallying cry was, ‘Get the furs while they last.’”

The entertaining, engaging narrative begins, in Part 1, “Furs Settle the New World,” with brief explanations of the roots of the fur trade in prehistoric times. From there, Dolin paddles forward through the centuries to catch up with English explorer Henry Hudson’s 1609 voyage to the New World, and the excitement caused in Europe by his journey’s discovery of this bounty of furs.

In Dolin’s confident treatment, we learn that that fur trade was much more than the clichéd crusty mountain men trapping and shooting everything that sprouted fur in the Rockies. (Indeed, there is more than a whiff of truth to that notion. Though many creatures played a vital role in the saga, it is primarily beaver, sea otter, and buffalo that were most prominent in the fur trade. And those populations suffered mightily for their contributions to this fascinating time in America’s formative years.)

The fur trade was a primary reason that the French, English, the Dutch, and the Swedes all scrabbled for land and the control ownership of it brings, and for subsequent westward expansion. Dolin goes on to chronicle the unfortunate effects the roughshod expansion had on Native Americans, whose increased dependence on cheaply produced European goods led to a long-term degradation of their lives and cultures.

The 420-page book is an engrossing read that offers focused access to three centuries of history surrounding a brutal, engaging struggle for dominion over a land that was already faring just fine for itself well before white European settlers ever thought to visit.

Bound Like Grass

In Bound Like Grass: A Memoir from the Western High Plains (University of Oklahoma Press; $24.95), author Ruth McLaughlin reveals how, by forcing the land to do something for which it wasn’t intended, her grandfather unwittingly set in motion economic and social oppression for subsequent generations. It would take the tired children of tired parents to break free of the doomed-to-fail experiment.

But even in the midst of strife and hard labor, the author reminds us in this engaging, yet unflinching poetic read, that lives are lived. Her book succeeds in capturing the stories of overlooked people, her people, who otherwise would have been lost to us. Though tinged with privation — she and her brother knew little of so many things people elsewhere took for granted: bowling, dancing, swimming, an indoor toilet — the author’s Montana childhood was also filled with good times in a loving family.

A by-product of this hardscrabble upbringing is the refreshing matter-of-factness of McLaughlin’s writing. As with any memoir worthy of the designation, the book offers its share of bare moments and raw, honest admissions. Among various introspections, McLaughlin probes her feelings toward her two mentally handicapped sisters, explores how the family’s life formed and stunted them, and how she felt she failed them, as a sister and as a fellow human.

She ultimately saved herself by breaking free of that life, if not fully the mindset of privation: “I still like potatoes that I tug in brown plastic bags into my grocery cart. I am relieved to be away from the heat and sweat and sunburn of hoeing and knocking off potato bugs, but these store potatoes seem like orphans, far from the fields in which they grew.”

With such simple, everyday elements, McLaughlin reminds us that no matter where we roam in life, we’re never far from home. How, despite our best efforts, we are all rooted to a place, like the prairie grass choking the plains of her youth. The trick, if Ruth McLaughlin’s life is an example, is to learn from the past and to not let it haunt you … not too much, anyway.

The Pony Express

It’s no surprise why The Pony Express: An Illustrated History (Two Dot; $19.95) by CW Guthrie, with photographs by Bart Smith, was published this year, during the 150th anniversary of the Pony Express. Its riders braved all manner of obstacles and impediments on the 2,000-mile trail. They dealt with swollen rivers, Indian trouble, unpassable mountain passes and the searing heat of brutal deserts, from St. Joseph, Missouri to San Francisco, California, and even cut through Wyoming in the process. In 1860-61 reenactors dedicated to preserving the trail and its historic significance in our collective memory retraced the route on horseback for 19 months, just like the bold riders of the Pony Express.

You can learn all this and lots more in Guthrie’s highly readable The Pony Express. The book is a 200-page oversized softcover richly illustrated with color and vintage photographs, illustrations, maps, and paintings. It’s divided into 10 chapters that chronicle the entirety of the Pony Express, from hare-brained inception through its still-mighty presence today, and is accompanied with a fine introduction, two appendixes filled with fast facts, a handy bibliography, an index, and more.

The Pony Express serves as a fine introductory guide for anyone interested in learning more about the history, the myth and lore, and the subsequent preservation of that daring, celebrated endeavor we all know as the Pony Express. Which, incidentally, still exists as the Pony Express Natonal Historic Trail.

Charlie Russell and Friends

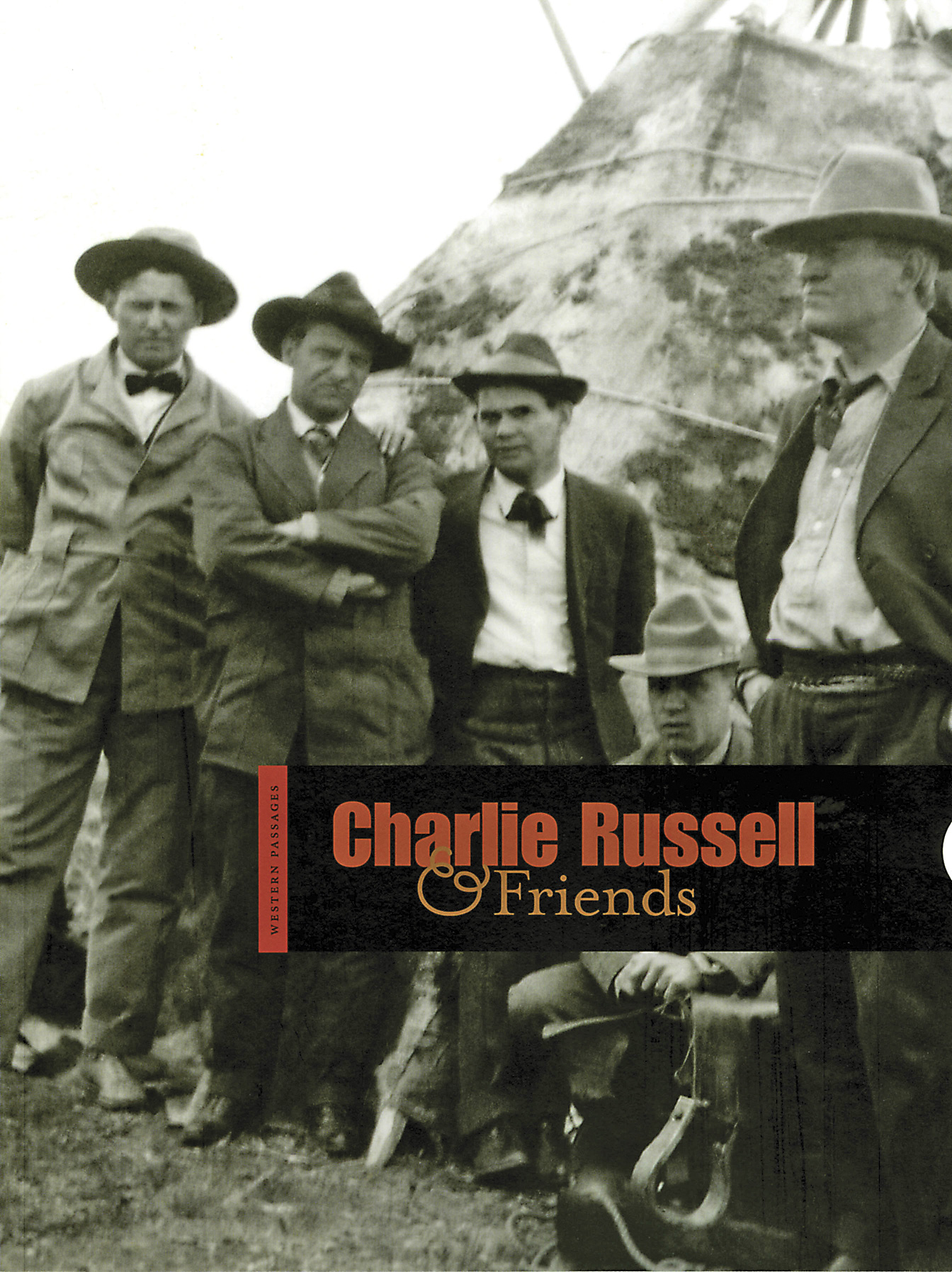

Though Charlie Russell and Friends (Denver Art Museum; $10.95) sounds like the name of a PBS evening filled with singer-songwriters, it’s actually an entertaining, must-have book for any fan of that penultimate cowboy artist. This 9- by 12-inch, 72-page paperback is filled with 48 color and 35 black-and-white illustrations, offering a fine mix of art and photography that explores and documents the artistic influences of lifelong artist friends of artist CM Russell.

Russell, by all accounts, was reserved enough in life that he was often considered aloof by those who didn’t know him. But beneath that scrim of grin, Russell was a gregarious sort who, when he made friends, did so for life. The book focuses on one of many groups of his friends, this time his artist chums, chief among them his protégé Joe De Yong, sporting artist Philip Goodwin and famous Southwest artist Maynard Dixon.

One glimpse of his illustration-embellished letters to friends is enough to convince readers that the normally dour-faced Russell was anything but aloof. Reserved, maybe. But only until he got to know folks. And judging from the ample supply of photos, stories and illustrations detailing his friendships with other artists, this was indeed the case. Russell couldn’t have been a loner if he tried. His influence on other artists, and their influence on him, is apparent on every page and every detailed caption of this book.

No Comments