03 Aug The Vibrancy of Nature

Patricia Griffin starts by telling me about the wolves. “There was a pack of them on my back hill this past winter,” the esteemed painter, photographer, and conservationist relays over the phone. She’s taking my call from her studio in Jackson, Wyoming — the reception isn’t great, but it does nothing to dampen her palpable awe. “I watched them from my window for days, just being dogs. It was magic.” Griffin spent so long tracking the wolves through her window that her binoculars left permanent indents, she jokes. Seeing a single wolf in the wild — let alone an entire pack — is a rare, once-in-a-lifetime event. Photos would have been nice, for posterity. But the wolves were just a bit too far away for Griffin to get a clear shot, an inconvenience she took as a gift. “My only option was to watch and be in that experience.”

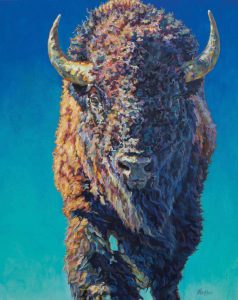

MARILYN AND MONROE VI | OIL ON LINEN | 40 X 30 INCHES

It isn’t unusual for Griffin to lose herself in nature, her persistent subject. In fact, giving herself over completely to her subject is the goal. As an artist, Griffin tries to be a conduit for emotion, channeling the ethereal experience of connecting with wildlife to her viewer. The resulting paintings are reminiscent of the most striking photography. Not on account of style, which is more akin to impressionism than realism, but because each artwork vividly encapsulates a fleeting, awe-inspiring moment in the natural world. Griffin’s instinctual brushstrokes seem to flex and flow across her canvas, coming together in a nexus of pulsing colors that transforms before the viewer. Step back, and the eye reveals a scene that seizes your attention.

HOME SCHOOL IV | OIL ON LINEN | 48 X 60 INCHES

Wildlife called to Griffin from a young age. She grew up in the Pocono Mountains of eastern Pennsylvania, where the woods were her playground. “I dreamt of fairies and all those things,” she says, laughing. “I used to hope the animals would talk to me.” Drawing was a way for her to capture and share her fascination. Griffin intended to study drawing at Moore College of Art and Design in the late 1980s, but the Philadelphia arts school had other plans for her — or rather, an oil painting class had other plans for her. It was the consistency of the medium — “so buttery, I just loved it” — that won her over, shifting her path: Griffin became a painter.

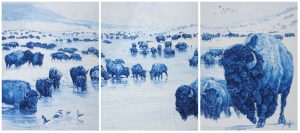

1856 | TRYPTICH | OIL ON LINEN | 40 X 90 INCHES

Experiencing the majesty of the Rocky Mountains shifted Griffin once more. As a college graduation gift, her 90-year-old great-aunt invited Griffin along on a senior citizen bus tour of the American West. “It was just me, a 21- year-old, with a busload of seniors,” says Griffin. She had a spectacular time. The tour ran a route from the Rio Grande’s origin in Colorado up to Yellowstone National Park, making stops at landmarks and gift shops. While the group browsed for souvenirs and snapped photos, Griffin would wander a bit further into the landscape to draw. The wild geography, flora, and fauna of the West struck something in her. “The mountains never get old,” says Griffin. An afternoon in Jackson marked one of the last stops of the tour. Griffin and her aunt wandered into the Million Dollar Cowboy Bar, an institution of the small ski town, to have a beer. “I remember I sat on the saddle stool next to my aunt and thought, This is my place.”

BELLA ROSA | OIL ON LINEN | 72 X 48 INCHES

Indeed, Jackson left an indelible mark on Griffin’s heart. In the years to come, as the artist established her studio and started a family in Pennsylvania, expeditions to Wyoming became ritual, then requisite. At a certain point, she ascended to the rank of honorary local. In theory, Griffin currently splits her time between the East and West; in practice, she hasn’t left Jackson in over a year. There’s simply “too much beautiful wildlife [in Wyoming],” says Griffin. “I can’t get enough.”

Griffin’s sublime compositions are a worthy match for the beauty of her surroundings. Her technique is a triumphant weaving of styles — Impressionism’s intuition and optical play; Fauvism’s bold palette and confident brushstrokes. Color vibrations — a science, not a turn of phrase — are a defining element of Griffin’s work. Consider two complementary shades — purple and yellow, blue and orange, red and green — placed side by side on a canvas. If the two colors have the same value (meaning relative intensity, from light to dark), both swaths will vie for attention, prompting your eyes to oscillate between shades. Which, in essence, creates a vibration. “I like to think of it as a dance,” Griffin explains.

APEX | OIL ON LINEN | 48 X 48 INCHES

Griffin leverages complementary colors with a painterly hand, applying layer upon layer of distinct brushstrokes that become strikingly realistic forms. Going into our interview, I’m excited to ask Griffin about her method — I imagine it requires extensive planning. How does she decide which color goes where, and when, and how will she ensure her small strokes come together to form the whole? But the artist’s approach could not be more different. She works from her photography and memories from affecting expeditions in nature. “When I see an animal in the wild, the passion I feel is just overwhelming — I’ve cried, I’ve caught myself weeping,” says Griffin. “So it’s that experience that I utilize in my work.” That’s where the planning ends. To be a conduit, Griffin tries to work without overthinking, concentrating on the emotion she felt when snapping the photograph. She makes decisions about colors and placement quickly, only considering the amount of warmth or coolness the canvas may need. The resulting style is a master class in the effects of intense, all-encompassing vibrations. Her colors appear brighter, more vivid and alive. It’s hard to look away.

BALTHAZAR | OIL ON LINEN | 60 X 48 INCHES

Griffin’s style is purposeful — her aim is to draw in the viewer, capture them in the spider’s web of her brushstrokes. “I want people, when they are looking at the work, to forget any thought that they had prior,” says Griffin. “I want them to come into the present and lose themselves in the subject and the paint application.” The best way to look at Griffin’s paintings is with “soft eyes,” a technique often used in horseback riding. Instead of honing in on a single point — in the case of Griffin’s art, a single stroke — widen your scope. Allow your gaze to relax until you’re looking, not focussing. Then, take a few steps back from the canvas. The line separating the strokes will begin to blur and meld, creating new colors altogether — as Griffin notes, she does not use a speck of brown to paint a bear, but, nonetheless, her depiction appears brown from a distance.

Throughout the canon of wildlife artwork, viewers often find themselves positioned as hidden observers, leaving the subject unaware that they have an audience. Griffin deviates from this course. Her subjects tend to meet their viewer’s gaze, staring back with large, calm eyes. The effect is extremely intimate — the animal is allowing you to see them, and they want to see you in return. “I love watching people react to [Griffin’s] work,” says Carrie Wild, artist and owner of Gallery Wild, which represents Griffin. “There’s a really cool interaction between the painter and the viewer. They step back, take a deep breath, and smile.” Wild appreciates the dichotomy that Griffin’s painting presents — while the artist often works on outsized canvases, her compositions feel warm and inviting.

ELDEDGE | OIL ON LINEN | 84 X 60 INCHES

The approach lends itself well to capturing both her subject and the passion that inspires each painting. At her heart, Griffin is a conservationist. A commitment to preserving the environment has always been the driving force behind her work — though she used to take a different approach. As a young artist, Griffin used her anger at environmental atrocities as motivation. She painted heart-wrenching disasters and heinous acts against the earth — nuclear bombs detonating under the ocean, for example — in the hope that her viewer would feel that same anger and act. “But then someone told me, ‘No, it’s not landing; it’s too beautifully painted,’” says Griffin. The emotion wasn’t coming through. So instead, she started to paint things she loves: ethereal encounters with the natural world. Beauty inspires a far different emotion than anger — deep appreciation, tenderness, awe — but with the same desired outcome: This beauty needs protection and care.

Griffin’s 1800s series perfectly encapsulates how the artist transforms her anger into beauty. The series explores wide-angle views of a large bison herd grazing peacefully near a river — a scene Griffin happened across while driving through Montana’s Blackfeet Nation. Blue and white are the only colors present in the collection, a rare departure from Griffin’s usual rainbow palette. The minimalism works to elevate each scene, allowing the varying shades of indigo, sapphire, and robin’s egg to pop spectacularly against the stark background. Looking at the works, I’m reminded of 19th-century toile fabric, replete with pastoral European landscapes — it’s so unusual to see the antique style applied to a quintessentially American scene. More often, art depicts bison trapped in the throes of a hunt as men with guns give chase on horseback. The 1800s series couldn’t be more different — here, the herd is without disruption, in harmony with nature.

BELE | OIL ON LINEN | 30 X 20 INCHES

As with all her work, Griffin hopes that people find their own meaning. For her personally, though, the series’ paintings are a story of healing. The reestablishing of bison herds is a conservation success story — not only because humans hunted the animal to near extinction in the early 20th century, but also because bison play an incredible role in supporting the environment. “They encourage the prairie grass to grow,” Griffin explains. That grass grows roots 11 feet deep in the ground, draws in rainwater and carbon, and keeps the ecosystem in equilibrium. “I don’t need people to know that that’s what’s driving the series for me, but that’s exactly what is driving the series,” says Griffin.

When I talk with Griffin, it’s early May. She’s hard at work on a commission from the Nature Conservancy, a painting of a bear for their pollinator campaign. After our call, she sends me a picture of a nearly complete work from this winter: six looming canvases depicting her resident pack of wolves. The composition has them running toward the viewer, racing in tandem. “I call it Dinner Party,” says Griffin with a laugh. It’s arresting — enough to take your breath away.

No Comments