30 May The Lookout Cat

U.S. Forest Service fire lookouts have one of the loneliest occupations on earth. Perched atop remote peaks across the West, we spend summer days in monk-like observation, eyes roaming timbered landscapes, watching the horizon for impending storms and wisps of smoke. When I was 24, the singular role and solitary life were what attracted me to the work, but during fire seasons in the Bitterroot National Forest in Montana, companionship still emerged from unexpected places.

Before I left for my first summer on Hell’s Half Acre Mountain, a friend warned me: “Take care of yourself. You’ll meet angels up there. But you’ll meet some demons, too.”

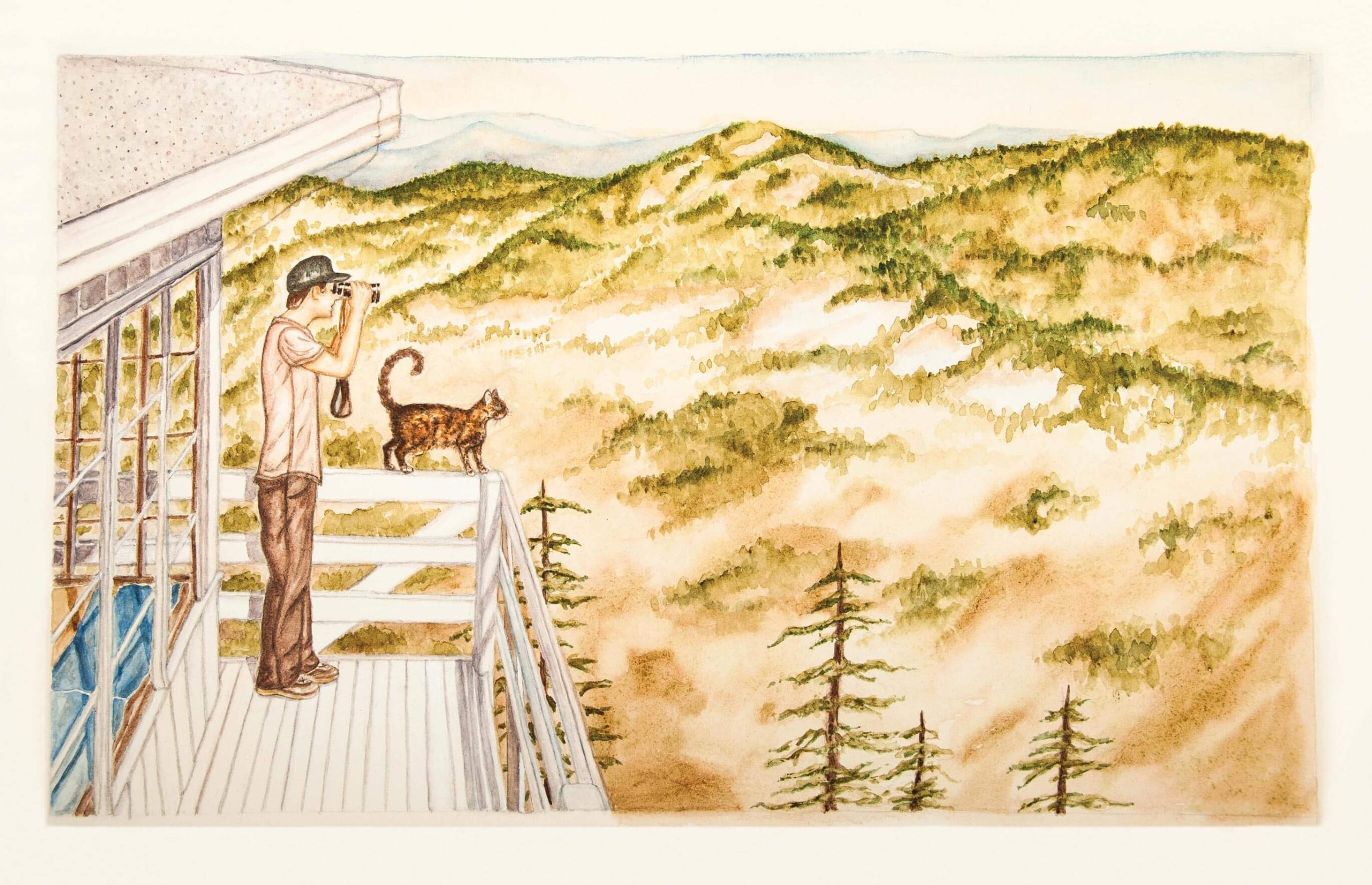

It wasn’t hard to find the angels. Before slopes turned the color of straw and withered under midsummer heat, before the lodgepole browned with drought and clung to each drop of moisture like crabs to sea cliffs, before lightning cracked overhead, it was easy to stay occupied. These early days were my favorite — snow melting into mountain streams, daily hikes to the spring, returning to the tower at sunset, and crunching through ice that was stained pink by the setting sun. Weeks passed on the catwalk, where I viewed the wilderness through binocular lenses, catching a hawk aloft on thermals, a mule deer descending a canyon.

The only demon was isolation. I was one of the few lookouts in the Bitterroot without a pet or spouse, and midway through fire season, simply living in the tower meant keeping company with only myself. Alone in a 14- by 14-foot room, I watched ballistic bolts of lightning flare into flame, conjure a frenzy of firefighting, then smolder back to inevitable silence. I waited in vain for the U.S. Forest Service to deliver mail. I studied the movement of ants on the windowsill.

In the mornings, I tried walking to look for signs of neighbors. Undisturbed for eight months, the last mile of the road to Hell’s Half was shaded under trees on the north-facing slope. Tracks appeared in the glittering ice like cave paintings, traces of creatures living and dying in a white tapestry: a snowshoe hare with its hind legs landing in long ovals, hand-like prints from ground squirrels skittering across the powder, cloven hooves of elk and deer.

One afternoon, I tried a new trail curving through ankle-high grass and a burned-over forest before it descended toward the river. I followed the path past nameless meadows, a patchwork of wildflowers draping the slopes with glacier lilies and their petals of gold.

When I reached the river, pushing aside a knot of low-hanging branches to see the emerald water echoing in cataracts around the canyon, other voices chattered. A cluster of green tents came into view. The tents belonged to the Montana Conservation Corps trail crew, and they beckoned me up from the water toward a pot of simmering pinto beans.

There were six of them: a woman from Alaska, another from Montana, a man from Connecticut, and three Midwesterners looking to swap cornfields for cross-cut saws. We shook hands, and Mark, the crew boss, gave me a cursory nod over their campfire smoke. Layla, a Montanan with close-cropped hair, stepped nearer and asked what brought me to the river.

“I’m the lookout,” I said.

“Oh, you’re Hell’s Half,” she said. “We heard your voice on the radio all week and made up lots of stories about you.”

“Really?”

“Oh, yes. You’re married and have at least two children. We can tell by your voice.”

“Spot on.”

“Am I?” she said, smiling.

I told her she wasn’t. Over the next half hour, Layla and I talked about the lookout job, and I learned she had grown up in Missoula. I told her it was a solo gig apart from the occasional day off and the company of books.

“Well,” she said. “Do you like cats? You sound like someone who likes cats.”

“Cats?”

“Cats,” Layla said. “I might have one for you if you’re interested. She’s my sister’s, but we’re both on trail crew this summer, and we need someone to look after her. I thought a lookout would be perfect.”

Layla told me the cat would make an ideal lookout pet. She was sure her sister, Olivia, wouldn’t mind, and anyway, the cat was 16. She deserved a quiet retirement home with a view. Could I go to Missoula tomorrow and pick up the cat?

I considered her for a moment. How would I bring bags of cat litter up to the tower? After a spell of solitude without human or animal company, did I want a companion up there who would not leave until I returned her in October? Then I remembered mice darting through the meadow, the nooks and perches around the lookout ideal for a cat’s roost. Other lookouts had dogs. Maybe a cat wouldn’t be so bad.

“I’d love to,” I said.

The next day, I drove four hours from the tower to Layla’s house near the University of Montana in Missoula. Dust breezed off my 4Runner as it entered town and cruised between neat rows of trees. I knocked on the door, and Olivia — slightly taller than Layla and with curlier black hair — answered. She led me into a living room lined with green wooden floorboards. Oil paintings and pop posters decorated the walls. Then Olivia stepped aside and pointed to the floor.

“This is Kiki,” she said.

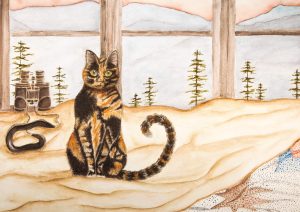

I stared at the small mound of mottled tortoiseshell fur she indicated. Then, a round head with wide green eyes emerged from the mound. Kiki meowed.

“She likes you,” Olivia said.

The cat stood like a garden gnome and looked up at me, mouth creased in a slight frown. I knelt and scratched her head. On closer inspection, one of Kiki’s ears was torn, and ridges of ribs stood out against her loose folds of skin and hair. Her mouth stretched back as I ran a finger under her chin — a front tooth was missing. I wondered how it would feel to call Layla from the lookout and deliver news that her cat had died, an uncomfortable image of digging a grave in the nearby beargrass already forming in my mind. It was a long way from Hell’s Half to the nearest vet.

Olivia carried out an igloo-shaped litter box and placed it on the floor beside 50 pounds of cat litter, two bags of food, and six cans of Fancy Feast.

“She likes the wet food best,” Olivia said. “But the dry food will last longer.”

We loaded the cat supplies into my 4Runner, and I folded the seats down to make room for a sleeping bag before my drive back to Hell’s Half the next morning.

“Does Kiki have a carrier?” I asked Olivia.

“No, but don’t worry. She’ll just sit on the seat next to you,” she said.

After a final grocery trip to buy a dozen more cans of cat food, I drove back to Layla’s, unstuffed my sleeping bag, and rolled an old sweatshirt into a pillow. Cracking the windows to ease the chemical smell of cat litter, I fell asleep on my side, wedged between a bag of Kibbles and an old chainsaw.

I was scheduled to check in from the tower at 8 in the morning. If 4 a.m. felt early to me, it must have seemed like an abduction to Kiki. She rode on my shoulder from the house to the car, meowing loudly in the predawn quiet, and she kept up an indignant growl after I placed her on a pile of towels spread across the passenger seat. Pinned under my windshield wiper was a note from Layla, who had arrived home for a day off during the night. She wrote about how happy it made her to think of Kiki “living her best life.”

As we drove, Kiki didn’t sound like a cat living her best life. Halfway down Highway 93, she climbed over the parking brake and dug her claws into my thigh; her face upturned in a glaring, green-eyed accusation. The meowing grew louder.

“I’m sorry,” I told her. “It’s going to be okay. Not much longer now.”

We were 10 miles from the tower when the vomiting started. As the 4Runner hit washboards and jarred against the pitted road, Kiki gave a sudden jerk, her neck elongated, and I had just enough time to brake before she retched on my jeans.

Check-in would have to wait. Stopping the car, I set Kiki down at the edge of the forest, under the cool shadows of ponderosa pines still damp from the morning mist. She lapped a few mouthfuls of water from her dish, and I hovered over her like an anxious parent watching a toddler totter toward the stairs. She let out a raspy meow and coughed.

“Almost there,” I told her. “Not long, and then no more car rides for another three months.”

The ride improved. Slowing the car to 5 miles per hour and coaxing it over each bump, I watched as Kiki sat up on my lap and peered out the window in silence with wide, owlish eyes. Maybe it was the change of scene from highway to wilderness, or maybe she had expelled all her energy along with last night’s dinner, but she quieted and continued to sit there, looking out the window at the endless wreckage of old burns. It was the first time I’d shared the drive all the way to the lookout with anyone. And, mile by mile, as we inched up the road and approached the tower, the little being in my lap was beginning to lift the loneliness.

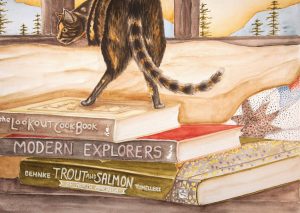

We soon developed a daily routine. Since Kiki was almost weightless and needed help staying warm, she would growl at sunset until I lifted the edge of the comforter high enough for her to curl up under the blankets and raise a small lump in the bedspread. Without any spring left in her legs, she would wobble down a small ladder of books I stacked beside the bed in the mornings. Then, she meowed at the front door until it opened, and she could pace the catwalk, stopping to sit like a sphinx in a square of sunshine bathing the east-facing boards.

Around lunchtime, she walked through the meadow, her brown and orange back disappearing beneath the beargrass, her tail a question mark moving between flowers while her small nose inspected butterflies. I stood close by to ward off eagles and hawks. Afterward, she fell asleep for hours.

When she awoke, she would take a few arthritic steps up the book ladder — Trout and Salmon of North America, Modern Explorers, The Lookout Cookbook — one hop at a time. She settled on the south-facing windowsill to begin her turn on watch, a feline lookout, her thin tail twitching as a Clark’s nutcracker flew from branch to branch on the pines and a hummingbird flitted between wildflowers.

I learned her favorite flavor of Fancy Feast (chicken and liver) and, on frosty nights with the wood stove lit, she would sit as close to the warmth as she could without singeing her hair on the hot iron.

After the last rays of sunset faded from tangerine to lilac, a blue darkness fell, our view devoid of artificial light. Overhead stars glimmered to life in their millions, stars numerous enough to overwhelm memory. Thousands of worlds whirled above in a blackness broken only by white meteors streaking across the atmosphere. When the moon was full, soft light slanted through the tower windows.

We would watch it together, the two of us, imagining the vastness of the void and how many mysteries it holds. Then, Kiki curled up, started to snore gently, nestled against me between the comforter and top sheet, both of us where we belonged.

Austin Hagwood is a writer, fly-fishing guide, and former fire lookout based in Missoula, Montana. He received a Master of Fine Art in nonfiction from the University of Montana, and his work has appeared in River Teeth, Appalachia, The Drake, and the National Geographic online newsroom.

Carol Ann Morris is a fly-fishing photographer, speaker, videographer, and artist/illustrator. She partners with her husband, fly designer and author Skip Morris, on his fly-fishing books, articles, and instructional videos. Her work has appeared in most of her husband’s 23 fly-fishing and -tying books, as well as in magazines and books such as Gray’s Sporting Journal, Fly Fisherman, Yale Angler’s Journal, American Angler, Fly Fishing & Tying Journal, and America’s Favorite Flies.

No Comments