30 May A Life and Journey Such as This

He was the quintessential Montanan, I think. That is to say, the landscape shaped him, as it shapes all of us fortunate enough to be here in this eyeblink of time.

Sometimes his music sounded like the first crack in an ice dam — that first tap of the jeweler’s chisel — and no matter whether the dam opened to the delicate filigree of a tiny thread of a creek back in a forest, or to an enormous inland sea filled with strange fishes and with all other manners of life — desire — inhabiting that sea, his music spoke eloquently to the dynamics of seasonal change.

What I hear in his notes is a singular exploration of the territory between contentment and desire, and those two conditions in the spaces and timing between the notes. Upon which side of that divide was he most comfortable? Perhaps he liked best the view from the ridge, looking down and seeing both sides. The view of the world.

Winston loved all of America with the passion of a gourmand — San Francisco, New Orleans, Mississippi, New York — but he loved Montana and her wide open spaces, the Hi-Line most of all. An aficionado of farm country, it seems fitting that he devoted so much of his career to supporting small local food banks. | Photo by JANIE OSBORNE

In Montana, we know this feeling well: the exalted views from the high country, but also those delicate days that exist between the four seasons. The goodbyes, and the anticipations.

Like the paintings of Russell Chatham and the poems of Richard Hugo, the music of George Winston helps us better see (and hear and know) our state.

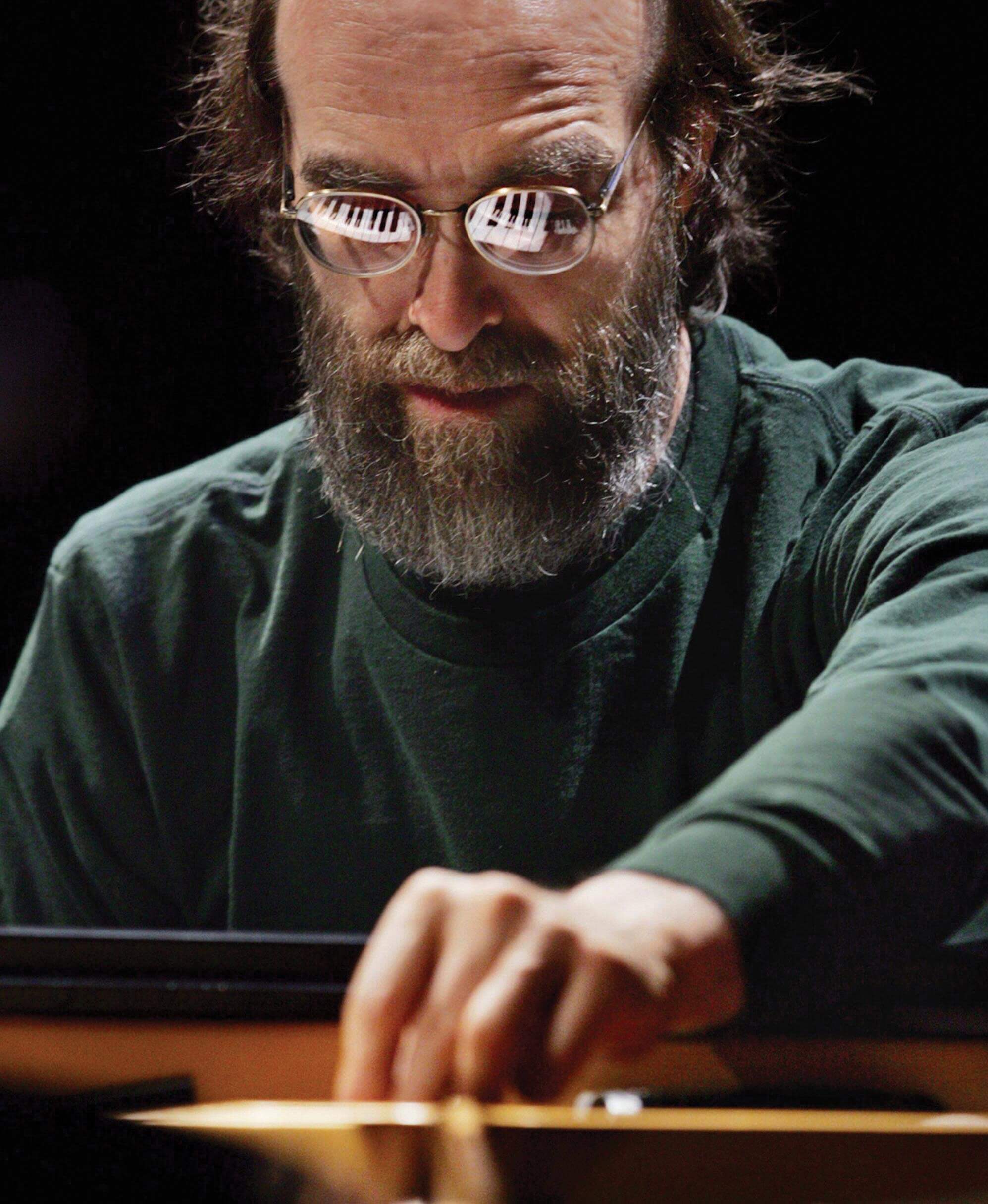

So often, humility accompanies true greatness. And he was certainly that. He would shamble out onto the stage with barely a glance at the audience. Mostly, he had eyes only for his beloved: the piano, or, before carpal tunnel syndrome began to interfere, the guitar.

Born in Hart, Michigan in 1949, Winston grew up and lived in two of what I think are the most iconic of American places — the Hi-line of Montana and the Deep South of Mississippi — landscapes powerful and direct in their ability to evoke emotion. Montana’s wide open spaces and — forgive the cliché — canvas of big sky authorizes in us emotions of similar amplitudes. Imprint those responses upon our brainpans long enough, and with enough repetition and force, and landscape will become character. That is to say, if we’re lucky, we become the place we live. This can take a long time, and I think in Montana, we all know instinctively to defend this smithy of ironworks where, to crib from James Joyce, our consciousness, spirits, and souls are formed.

Self-taught and hugely influenced by American blues music, Winston found in the landscapes and seasons of rural America the time and spaces to experiment and grow: a master who went his own direction, with grace. | Photo by TODD V. WATTSON

Mississippi, likewise, with its lush bounty of vegetative uproar and the delicacy of social mores — hospitality overlying the veneer of (like much of America) a culture built on violence — has shaped so many artists. Atop such history, who wouldn’t crave gentility, manners, peace?

I’ve lost my hearing in one ear: shotguns, chainsaws, and standing in front of 10-foot-tall speakers with my daughters at a Dierks Bentley concert. Extreme attentiveness has been described as a form of prayer, and I will say that the absence of sound in one ear has created a delight for that which I can still hear in my other. It seems sometimes I can see or feel — as much as hear — the sound waves. Different tones sink lower and bend, wrapping around corners in a room, even as other registers of sound move like unseen herds of animals through higher levels and strata, traveling faster and bouncing off one another rather than sliding around the contours of things. The delicate and the emphatic. The sublime and the exclamatory.

Photo by JANIE OSBORNE

An interviewer, speaking to the delicacy of Winston’s piano notes, was reminded by Winston that the piano, despite being stringed, is “a deeply percussive instrument,” requiring significant force to elicit any note. What Winston did not point out was the paradox and challenge: playing something delicate and nuanced that has been trained to be pounded.

His hands were his voice, his hearing, both composer and composition. He did everything he could to teach the strings subtlety. While playing with his right hand, he would reach into the maw of the piano to calm if not shush them. He would use his fingertips, even fingernails, to elicit sounds from certain keys. It is said one of the qualities of love is patience, and he was both hungry for yet patient with the sounds — the music — that he shared with us — created — all his life.

In W.S. Merwin’s poem “Berryman,” the poet writes, “… his lips and the bones of his long fingers trembled / with the vehemence of his views about poetry.”

It must have been lonely at times, to be so in love with the ineffable, but genius must also have made the most divine company — again, as much as the landscapes that dazzled him. The poet Mary Oliver’s words from “The Swan” come to mind: “… Said Mrs. Blake of the poet: / I miss my husband’s company — / he is so often / in paradise …”

Photo by JANIE OSBORNE

Regarding the patient timing of his notes — the pause and spaces between things, and then the way they rejoin and rush together: His sense of time seems perfectly attuned to the seasons. For a long time, I have had the fanciful notion that we are so very wrong with our estimations and perceptions of time. Because we are thinking about a thing, an abstraction, which therefore can’t even really exist, how can we possibly get it right? Like trying to define the boundaries and advance of “beauty,” or any other abstraction. Maybe there is just the physical material of the world, which undergoes erosion, disassembly, reassembly — and we are trying to figure out how to box that disarray and reconsolidation into seconds and minutes. But wouldn’t it make sense for time, if it even exists, to be a physical force, like wind or water or fire? Like everything else that is real in the world.

Another way Winston was a quintessential Montanan is that he was composed of the four seasons. The deeper into the burning we go, the further and farther we drift from that homeland, that assurance, of change. The seasons’ movements, and therefore the world’s, often seem spastic, whip-like, so that I wonder if there’s been some crack in an ice dam somewhere — an ice bridge of time — and that, in this time of great burning, we are all tumbling into a territory our species has never inhabited before. In his music, however, we hear the sky and the meadows and snow and rain and the rivers that then tumble in snowmelt, and we know that the seasons are always coming back.

Another attribute of greatness, I think, is generosity. The list of benefits he played around the state, and the country, seems endless. Each year Winston came to Libby, Montana to play for the food bank. His website (georgewinston.com) is endearing for its wonkiness, footnotes, and deep-dive explorations of the arcane and the minute: snapshots of how sublime he found the things that others typically do not hear or see. There’s little preamble in his essays; instead, he just gets right down to it, as if taking transcription from the gods.

That such an unassuming and unambitious soul should have known such extreme commercial success makes him seem all the more from a different time, which — with time moving so quickly these days, I guess he was. Five Grammy nominations, a Grammy award, and over 15 million albums sold.

Physicists tell us that sound waves are the only of the five senses that are not repackaged in the central nervous system of the brain — the other four senses becoming, essentially, a kind of metaphor, in that processing — like this, unlike that. Physicists also remind us that the vibrations of sound waves — the trembling they set up in the bodies of the objects that receive them — no matter whether the animate or the inanimate — resonate forever, even if in frequencies so diminished we can no longer hear them. But we feel their echoes, forever.

Winston was fond of reminding people that the piano is a percussion instrument. | Photo by REED SAXON

I think of Winston and his music sometimes when I am in a colony of aspen. Quaking, we call it. Quaking with joy, or — that word — yearning. Trembling aspen. The rush and clatter of the sound, in each of the four seasons. Fire summons aspen. They never leap so exuberantly as after a fire — they have been waiting, in the roots, the one-root, one-organism, that is the through-line of any aspen colony — the underground colony of joy. They have been waiting to hear the fire rush over and past, and for the sky to open up, and to leap up into it and into the flames of the four seasons, the flames of the brief living. (Like humans, aspen rarely live to be more than 100 years old.)

Night, we can tend to forget, sharpens the day. I think every artist begins their journey with the touchstone of another’s work. The touchstone reassures the beginning artist, You are not alone, and yet jolts the artist into the understanding that there can be a territory previously sensed, but never seen or known; a landscape where a slightly different logic exists, where even the rules of physics may be bent and re-shaped to abide by the beginning artist’s aesthetics. For Winston, the jazz piano of Professor Longhair was a foundation — Winston writes about this with great enthusiasm on his website — and so, too, was The Doors’ 1967 album, Light My Fire. As a young man, Winston attended a Doors concert and wrote how moved he was by the delicacy with which Jim Morrison sang the title song, giving emphasis only to the word “fire” in “Light My Fire.” It was for Winston a simple lesson of proportion — the quietude sets up the coming roar — though when I think of Winston’s etudes and nocturnes, it seems to me his intent, no matter whether subconscious or conscious, was to attenuate the quiet — the rill and run of a diluted storm’s slow approach — for as long as possible, until somehow — how can this be? — the storm has passed on not with Morrison-esque drama, but has instead been absorbed, modified, by that artful attenuation. Embedded in beauty.

It’s perhaps impossible to separate the sensibility of Winston’s music from that of the four seasons. The enormous power of spaciousness informs many of his compositions, with Montana’s singular qualities guiding them. | Photo by JANIE OSBORNE

What a calm he must have known at times, being able to tame storms. Not silencing them, but sculpting them into something else — spring rains, falling snow, wind in dry grass. Converting them into a more sustainable beauty. Wrote Eudora Welty, regarding the absence of storms, “A quiet life can be a daring life.”

For Winston’s mentor, Jim Morrison, thunder and lightning cleaved the earth as well as the soul; it seems fair to say Morrison perceived life as possessing a stone wall that must be broken through to reach the transcendence of the other side. Kafka wrote famously of the pen being an ax that could break open “the frozen sea within.” But for Winston, night was not the enemy of day, but its own treasure and delicacy. “The night has many colors; they’re just more subtle,” he wrote. “And I am nocturnal.” His last album, Night, presents a world that doesn’t exist on a 24-hour clock, but instead only between midnight and 7 a.m. In addition to the night possessing its own beauty, there is beneath and within his album the physical and spiritual grace in his depiction of what he called “solitude and uncertainty.”

His family, writing on his website after his death, described Night as “a portrayal of Winston’s place in a chaotic world — his compositions extend solace with an idiosyncratic grace.” Night celebrates “solitude and uncertainty,” they write. “Yet it is also a world, or a condition, where each passing hour brings a traveler closer to dawn.”

Sometimes the names of things matter, and other times they do not. Self-taught, he called his style, his sound, folk piano, rural folk piano, stride piano, jazz piano. Yes. All of it. As large a spirit as the landscape and the world allows.

Photo by TODD V. WATTSON

Most musicians come to their art through studying a classical canon. Comparison, it’s been said, can be the thief of joy — but if one did have to choose, say, between the study of what came before — the classical tradition — or the study of what is going away — the web of natural grace and seething, clamant diversity of the natural world — the pull of tides, migrations of cranes, pulse of seasons — what’s called genius loci, the spirit and genius of place across time so deep we need a different kind of clock to even think about it, with all living things becoming riders on the storm, struggling for the grace of mere existence and sometimes, for a moment, perfect or near- perfect fittedness, like one note played with the right hand, enriched by the different note being played with the left hand… Well, if one did have to make a choice — if, say, time was short — who among us would not choose to travel Winston’s route? His path was not so much a repudiation of structure and tradition, but instead an embrace of a greater complexity. There is a wild vitality to such curiosity. To such a journey. To such a life. How could we not, upon hearing such music, lean in closer and listen?

Rick Bass lives in the Yaak Valley of northwest Montana, where he is co-founder of the Yaak Valley Forest Council (yaakvalley.org) and The Montana Project (montanaproject.org). He is currently working to help defend the ancient forest at Black Ram and planning Climate Aid 2024, to be held in Montana later this fall.

Nancy

Posted at 19:44h, 18 JuneAloha Rick,

Mahalo for writing this charming and poetic article about my beloved brother.

Nancy Winston Kahumoku

George Kahumoku

Posted at 02:30h, 19 JuneMahalo Rick. Bass

Im GW’s brother in law

Come visit us on Maui