24 Aug Home Waters

Pilgrimage

By: Carter G. Walker

THROUGHOUT MY 20s, I spent every one of my birthdays in bad weather on a beautiful river in Idaho. As a child in St. Louis, my April birthday paired naturally with Easter bonnets and Cardinals season openers. But in my 20s, I was compelled — for reasons I didn’t know then and probably couldn’t explain even now — to undertake a 400-mile, white-knuckled drive from my home in Montana to the Salmon River near Stanley, Idaho, in the pursuit of Oncorhynchus mykiss, steelhead trout.

My trip, it turns out, was nothing compared to theirs.

The steelhead lifecycle is basically the piscine version of Ernest Shackleton’s help wanted ad: “… hazardous journey, low wages, bitter cold … safe return doubtful … ” The prospect of catching the wily survivors is equally grim, although, like Shackleton’s ad, landing one promises “honor and recognition in event of success.”

Anadromous rainbow trout are hatched in cold freshwater streams, sometimes barely a trickle. After spending a year or more in their home waters, they are urged by biology downstream and eventually to the Pacific Ocean, where they metamorphose internally and externally into saltwater fish. Their geographic range, from the California coast up to the Aleutian Islands, is driven by some mysterious internal GPS. And when, after three or four or five years, it’s time to go home again, these remarkable creatures transform for a second time as they evade death and capture — through dams, dam-stalking sea lions and scads of anglers, not to mention all the usual predators — on their 900-mile journey back to their home waters, all without a morsel of food. With less than one-half of 1 percent of Sawtooth Fish Hatchery steelhead making it to the ocean and back home again, their prospects are bleak at best.

But biology is biology. And as those fish fought their way home, I returned too, year after year.

I learned early on that when it comes to steelhead, fishing is a misnomer. What it is, is hunting. For 10 years, I braved blizzards that blew sideways. I covered dozens of road miles every day, looking for dark shadows in the water that could be fish. I waded through currents that could have taken down a man twice my size. And as often as I pissed them off, with brightly colored streamers that worked like a matador’s cape, they pissed me off plenty too.

But still I persisted. Despite boyfriends and jobs and plenty of other waters that were much nearer and probably not remotely as unpleasant. I kept hunting for those fish because, despite the discomfort, I loved it. From my brain to my frozen fingertips, my senses were super-heroically honed. I could think fish. I could be water. And the moments we met — the fish and I — were unforgettable.

And then one day, like the clockwork of fish biology, something changed.

I turned 30, bought an old house that needed work, married the love of my life and had two daughters of my own. Though the steelhead — still enslaved by their incomprehensible genetic drive — continued to make their journey year after year, I stopped. Driven instead by a biology that was no less powerful perhaps, but far more pleasurable, I fished closer to home. In better weather. And water that was shallow enough to be safe for my then-wobbly girls. I wore straw sunhats instead of fur-lined Russian-looking numbers. I spent more time prepping the picnic basket than the fly box. And the meetings with the fish, when they happened, no longer held the intensity of union between hunter and hunted. Instead, they were splashing, often clumsy events that involved quick pats from giggly girls, and the occasional photo, before the fish was back on its way to wherever it was going.

I haven’t been steelhead fishing on the Salmon River since I was 29. But as my girls grow older, stronger, and ever more wily themselves … I wonder if that drive will awaken in me again, urging me back to those waters I knew so well. I wonder if I will teach them how to hunt fish in a blizzard.

Until then, I am content to believe that home waters are where we make them. And that mine, these days, look more like paradise than anything.

Waters Forgot

By: John Heminway

COME EVENING, I slip into the waters by the cabin, facing the crumbling cliff where someday I am certain I will discover tipi rings. I will never know these waters unless I’m numb from the knees down. In sandals, I stumble, feeling the tug of riffles, the recipe of stillness and just how the shade advances and where that old brown holds. My evening safaris are not just about easing eyestrain, suspending ringtones, curing the melancholia of a completed task. I’m after continuity. And it’s all in vain.

Neighbors, the fourth-generation ones, don’t like me calling our home waters a river. Not wanting guys in Orvis hammering on their doors for permission, they urge the mapmakers to call it a creek. I am OK with their conspiracy except for one month a year, when our waters turn into Guinness, attacking foundations and howling through the night. In late May and early June even our lab knows not to chase sticks. One June I heard “the creek” make lunatic church bell harmony as it jackhammered cottonwoods against the flatbed steel bridge. “What d’ya say now?” I wanted to ask one of our Norwegian neighbors.

In late July evenings, there is only me to insult. I play the bends and gravel beds, and clamber over a beautifully engineered beaver dam, somehow knowing I am on my way to another bruising disappointment. I will let my Chubby Chernobyl drift once, twice. On the third cast he’ll swallow. Damn, OK, four. I pivot to face the opposite bank and study that tangle of roots where yesterday’s hopper is still draped like a cheap earring. Do I dare? My cast enchants only me. So, I trudge upriver to make a last drift into the sure-fire pool by the bridge where there is shade almost all day and the water is deep enough to house a boatload of 20-inchers (no kidding), that once I even had the good manners to show my father-in-law.

Most evenings I return in dark with nada — not even a story. This river — sorry, “creek” — is only repaying one insult with another. You see, years before we got here, a certain master of the universe, holding the deed to one side of the creek, got into his D-8 Caterpillar and straightened “the damn thing.” Seems he did not want to lose any more acreage to high water. He wasn’t an angler.

When we got the deed, two government agencies helped us return the creek to anarchy. In two months there was shade, new cottonwood banks, and seven deep holes where there hadn’t been any. “How long will it take a brown trout to find them?”

I asked the engineer.

“Two minutes on a slow day.”

Then came June 2012. The waters almost reached the bridge, boulders the size of yachts careened downriver, gravel bars split the current in two and half the cottonwoods we planted headed for the Gulf of Mexico.

One dusk, in late July, with the flood subsiding, home waters and I were reacquainted. It was then I learned that the sure-fire hole under the bridge was now a gravel bar. I sloshed upriver. That’s when I discovered that where the waters dogleg behind the sandstone cliff, there were two new pools, one deep. Even though shade only gathers there late in the day, and the browns are still wary, I feel I have won the lottery.

Home waters are ephemeral, much like ownership.

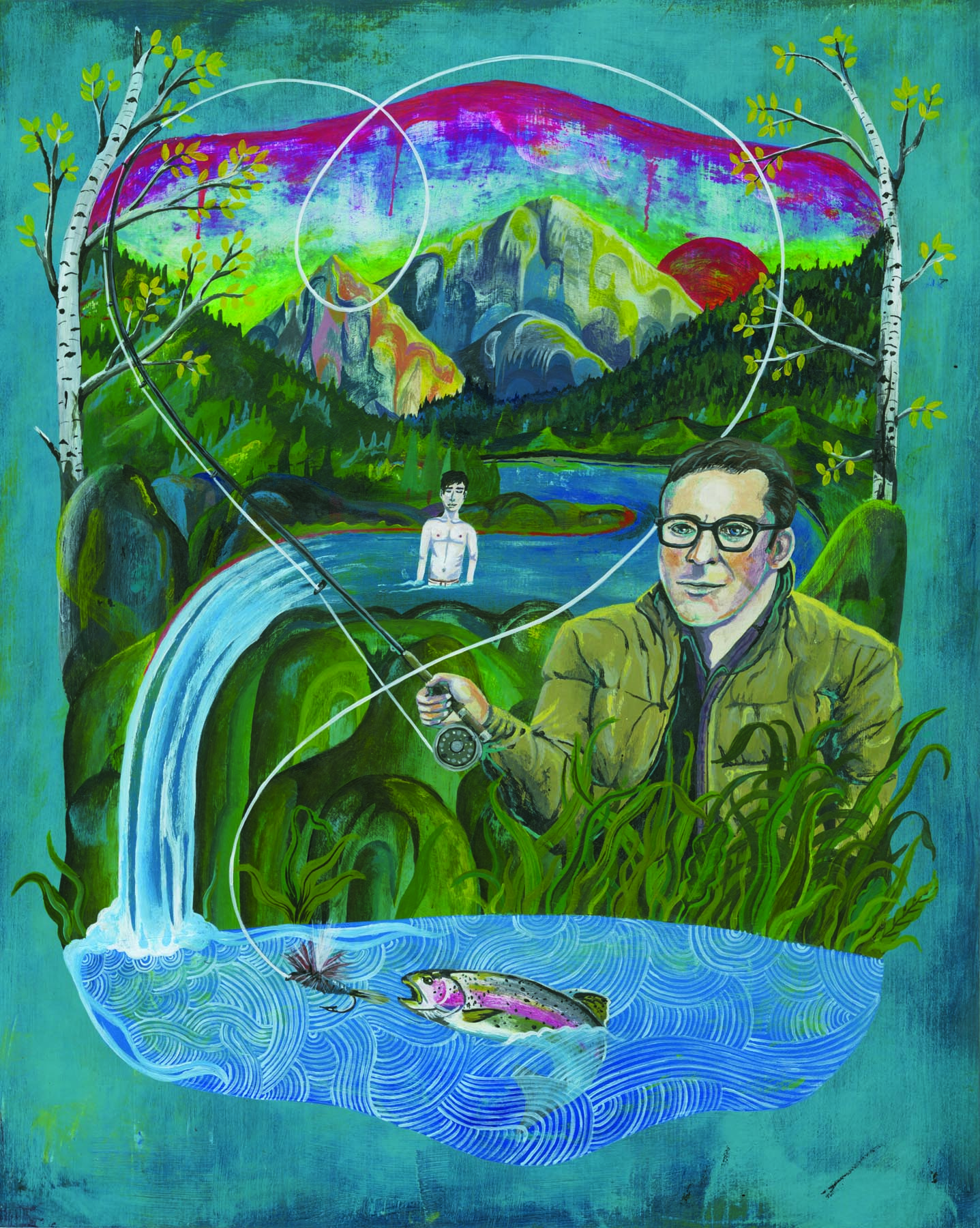

The Inheritance of Water

By: Shann Ray

AS A BOY, I walked with my father along the Yellowstone River on the northern edge of the Beartooth Range, south of Livingston.

We walked with a purpose and looked intently into the clear pools. Sun filled the basin. The land held the gold and silver of grasses, hardy cottonwoods along the river, the black and grey of rock promontories and the dark green of forests that reached behind us to the sky.

I was 14 and the world was new. A freshman in high school, manhood seemed far off. Into the river we went. Up to the waist in water, I felt contained by water and light. I felt the river push against me. I wore jeans and old shoes. Bare-chested, I leaned back and the water held me in place. I was small. The river was big. My father stood upstream in a flash of sun over the ripples. A giant. A shadow. He moved his hands over the water. A Parachute Adams, brown-bodied, with rust in the tail and the signature white crown, flew overhead and came to rest on the water at the top of a draw below a large rock. My father’s line jumped and bowed, moonlike from his outstretched arm, and he called to me. I shouted back to him. He drew a rainbow from the river and we smiled and laughed and kept on until we had enough for dinner.

Balance this against the aggression we sometimes felt for each other, that and my own fears of life without him leading me. Fly fishing is a subcurrent of life, or perhaps it is all of life, a passage strewn with daunting obstacles, brambles and gnarled trees, cut banks and the laddered spill of whitewater carving its descent through rock. Smoothness in the outflow. My father and I have always loved rivers. In the demanding presence of a landscape too beautiful to be named, the art of fishing, of becoming an authentic fly fisher, is not something that occurs quickly. In fact, my own early failures fly fishing remind me in their way of the blame I placed on myself and the gravity of incomprehension, emotionally blunt instruments through which every fish seems to pass beyond reach. And yet we improve. We gain headway. Sometimes our fathers lead us deeper into the realization that a line laid down with precision and elegance over good water contains unforeseen possibility.

There is a wilderness in me and my father, and in the life of everyone I know. In Montana the sun fills the sky with light. The loop of the line and the fall of an Adams Parachute, the miniscule lie of the white tuft on the surface of the big river, the rise of something from great depth … on the water a sincere call is followed by an ecstatic response — and one almost hears the world asking us to leave ourselves behind, the ache of our woundedness, the immutable fires and great losses. Can we love others more than we thought possible? Can we atone for the distance between us? Now when I see my father in the long light of evening, the river purling at his waist and the fluid arc of his arm in the sky, I am reminded that affirmation speaks, unexpected and steadfast, and sets the soul at ease.

No Comments