09 Aug History: The Matisse of Ceramics

Rudy Autio helped start the residency program at the Archie Bray Foundation for the Ceramic Arts in Helena, Montana, in the 1950s. In doing so, he helped to launch one of the most well-respected ceramics institutions in the U.S., while also establishing his legacy in the contemporary art world. He went on to enjoy a distinguished career as one of the most beloved art teachers at the University of Montana (UM) in Missoula. And while he made a name for himself early on as one of the country’s premier Abstract Expressionist sculptors working in clay, he achieved his most enduring fame as a maker of large, decorated platters adorned with dancing figures so imbued with a sense of movement that more than one art critic described him as “the Matisse of ceramics.”

The child of Finnish immigrants, Autio (1926–2007) was born in Butte, Montana. As his colleague at UM and friend James Todd remarked, “You can’t really understand Rudy Autio unless you know that he came from Butte.” His upbringing in the hardscrabble mining town during the depths of the Depression informed his work in more ways than one. For starters, he developed an indefatigable reverence for the industrial materials used in art, and once remarked to fellow artist Ted Waddell, “Wood is good, and steel is real, but clay is the way.”

GLASS SLIPPER 2006 | Stoneware

34 x 22 x 16 inches

Butte exerted its influence in other ways, too. “My background [in Butte] is so entirely un-rural that you can’t believe it,” Autio reminisced to LaMar Harrington in a 1983 interview archived at the Smithsonian Institution. “I never went out riding horses or farming. … City life is what I knew and kind of grew up in — tenements, one right next to another, three- or four-story tenements. No yards, no lawns. It was like living in Brooklyn.”

After serving in the Navy during World War II, Autio went to Bozeman on the GI Bill to attend Montana State College (now Montana State University), where he studied art. And after taking classes taught by renowned ceramicist Frances Senska, he fell in love with clay. One of his classmates was Peter Voulkos, who also went on to make a name for himself as a pioneer in contemporary ceramics. After college, the two friends worked as the first resident managers for the Archie Bray Foundation and helped transform it from an industrial brickyard into the renowned institution it is today.

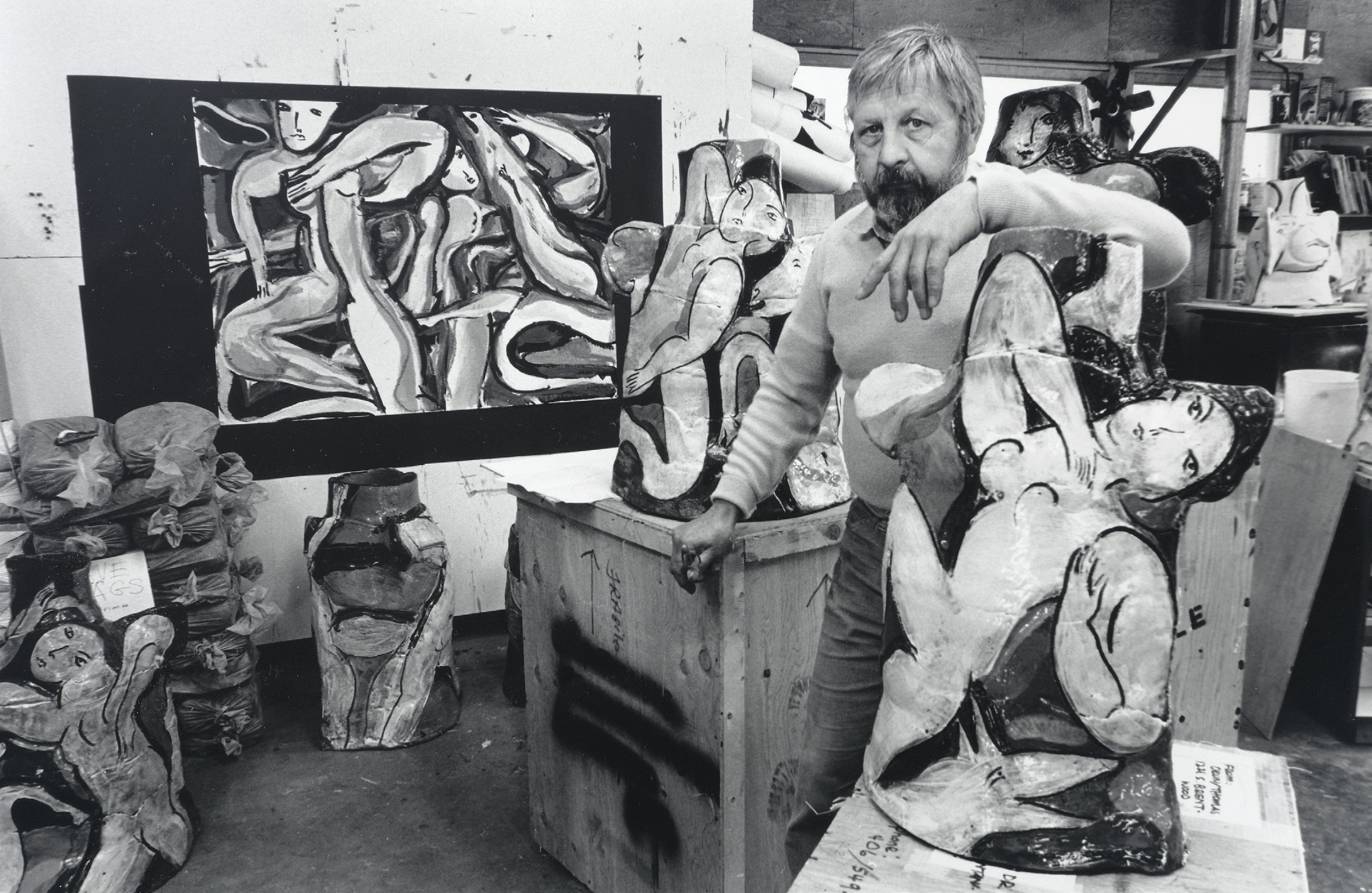

Along with being one of the most beloved art teachers at the University of Montana, Autio became known as one of the country’s premier Abstract Expressionist sculptors working in clay.

While Autio was employed at Archie Bray in the 1950s, he was commissioned to compose wall-sized murals for many buildings around the state. These included narrative and figurative ceramic compositions with a style that was in part reminiscent of the Works Progress Administration aesthetic of the 1930s, which included Neoclassical and Art Deco elements. These projects also clearly reflected Autio’s upbringing in Butte, a working-class city with a variety of ethnic communities.

A good example from this period is the 30-foot-long mural, “Sermon on the Mount,” that adorns the side of the First Methodist Church in Great Falls, Montana. It was composed of more than 500 stoneware tiles and completed in 1954. Autio’s decision to present Christ from behind, with the multitudes facing the viewer, challenges the typical iconography even as it reinforces the gospel message. The lines of the carved brick in relief resemble the woodcuts that illustrated the earliest printed books.

“Sermon on the Mount,” a 10-by-30-foot mural made from more than 500 carved bricks in 1954, hangs on the north wall of the First Methodist Church in Great Falls, Montana. Autio added himself, along with his friends Peter Voulkos and Cyril Conrad, to the audience that’s facing Jesus.

In 1953, when Voulkos returned from a summer residency in the town of Black Mountain, North Carolina, he had abandoned his traditional approach to wheel-thrown pots and, instead, had a newfound enthusiasm for abstract forms, an aesthetic turnabout that swept Autio in as well. Soon afterward, as art historian and critic Rick Newby noted in the catalog for Autio’s 2006 show at the Holter Museum of Art in Helena, Montana, “the two young mavericks in Montana [launched] a revolution that would forever alter the character of American — and world — ceramics.”

OLD BROADWATER

Oil On Panel | 37 x 27 Inches | Courtesy of Lisa Autio

In contrast to Voulkos, however, Autio eventually abandoned Abstract Expressionism. Though he made enduring contributions to the movement with numerous untitled works, he once remarked that he never felt he “quite had a handle” on Abstract Expressionism. In his memoir, It Comes Around Again, he states that by the 1970s, he felt the movement had ossified. His piece called “Stoneware Vessel” (1963), for example, exemplifies the almost violent amalgamation of clay slabs that were included in the brute Expressionist form and redeemed by a vibrant polychrome glaze.

In the mid-1970s, Autio began experimenting with figural drawings on ceramics, a turn that he soon realized would guide the rest of his life’s work. At a university workshop demonstration, he was challenged to “do a figure.” Though nervous, he acceded, and that impromptu shift before a live audience marked a new artistic trajectory that many critics and fellow artists — including Todd and Newby — claim resulted in a body of work that, more than anything previous, has defined the artist’s enduring legacy. Autio’s “central achievement of the past 25 years” was the elaborate construction of “large stoneware (and sometimes porcelain) vessels upon which he paints lovely and colorful dreamscapes, where women cavort and horses gambol within an impossible joyous space,” Newby wrote in the 2006 Holter Museum catalog.

Later in his career, Autio achieved fame for the dancing figures that deco-rate much of his work. They were so imbued with a sense of movement that more than one art critic described him as “the Matisse of ceramics.”

Autio’s 3-foot-high vessel made in 1986, “Goodbye to the Girls of Galena Street,” for example, exudes the kind of stately motion captured in the finest classical Greek urns. But at the same time, it possesses the expressive power of his earlier abstract work, as the drawn women seem to contort themselves to each other’s presence in an endless carousel around the face of the piece. Autio’s title, meanwhile, pays homage to the red-light district in uptown Butte, where for almost half a century, brothels and “cribs” lined both sides of Galena Street.

Over the years, the Butte that Autio grew up in changed, and so did the artist. The stark energy of his abstract expressions in clay through the 1960s became channeled into his figurative vessels — sculptural creations with swirling movements that evoke not just the style of classical Greek potters, but also that of the Japanese, Fauvists, and Post-Impressionists, like the French artist he’s been compared to: Henri Matisse.

The Yellowstone Art Museum in Billings, Montana, is exhibiting the work of Rudy Autio and his wife Lela, from July 29 to October 3, in a retrospective called Montana Modernists.

Aaron Parrett is a professor of English at the University of Providence in Great Falls, Montana, and runs a letterpress shop called Territorial Press in Helena. He has been widely published in many fields, and his most recent book is a collection of short fiction called Maple & Lead. He lives with his wife and daughter in Helena.

No Comments