30 Nov Books: Reading the West

Thunder in the Mountains: Chief Joseph, Oliver Otis Howard, and the Nez Perce War by Daniel J. Sharfstein (Norton, $29.95), is a hefty and thoughtful examination of the widely studied 1877 Nez Perce War. Sharfstein, a professor of law at Vanderbilt University, offers a nuanced view of that summer’s dramatic events, and provides thoughtful context for the action-packed story of one of the most famous clashes between a Native American tribe and U.S. military forces in the late 19th century.

The refusal of Chief Joseph and the Nez Perce to move to a reservation looms large in the history of the era, taking place in the aftermath of the American Civil War and George Custer’s ignominious defeat at Little Bighorn in the summer of 1876. Both Chief Joseph and the legal authorities of the time knew that their actions would have far-reaching repercussions. The Nez Perce had been forced repeatedly to give up territory around their traditional homelands in what is now Northern Idaho and Eastern Oregon and, despite protests from their leaders, were about to be relocated onto a reservation. Chief Joseph opted instead to lead his people across Idaho, into Yellowstone National Park, and then north through Montana toward Canada. The series of confrontations that took place in the summer of 1877 — as the fleeing Nez Perce were pursued by the U.S. Cavalry, led by General Oliver Otis Howard — ranged over 1,000 miles, stretching from the Nez Perce traditional homeland to what is now known as the Bears Paw Battlefield in Northcentral Montana.

General Howard, the namesake of Howard University (a historically African-American college in Washington, D.C.), was a Civil War veteran who thought he had found his destiny as an abolitionist. He lost an arm early in the war, and distinguished himself on the battlefield. Howard was known for his piety and his zealous commitment to the Union cause. After the war, as the civilian leader of the Freedmen’s Bureau (the organization tasked with helping former slaves transition into their new lives), he became disillusioned by the corruption and collapse of Reconstruction. In the 1870s, he opted to rejoin the Army and take on the mission of “civilizing” Native Americans by supporting the policy of moving them to reservations and teaching them to be farmers.

Sharfstein’s choice to frame this history as a clash between the destinies of Chief Joseph and General Howard — and his analysis of the connection between racism and American expansion in the 1870s — makes this book contemporary and relevant. He relates the events of that violent and heartbreaking summer with crisp language, vivid images, and absorbing detail, putting readers on the spot during local events and on the battlefield. This is an excellent account, and even readers who are familiar with the story of the Nez Perce’s famous flight will find much to discover in its text.

No battlefield memorial or historical fort informs both the myth and the historiography of the late 19th century as much as the indelible image of the cowboy on the open range. In Cattle Kingdom: The Hidden History of the Cowboy West (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, $29), author Christopher Knowlton explores the true story behind the iconography by studying real-life examples of the cowboys and rancher-investors who shaped the world’s view of those men. His book takes both close-up and broad-angle views of the way the cattle industry molded the West. He makes the subject come alive, burnishing the image celebrated in fiction and film even while demonstrating his thesis: that the era of the great cattle drives didn’t just impact our view of American history, it also had a major effect on the economic and political landscapes of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The influx of cash from the East helped Western cities rise from the prairies, and the flood of beef from the West into the East changed the relationship between the frontier and “civilization.” But the boom didn’t last long.

No battlefield memorial or historical fort informs both the myth and the historiography of the late 19th century as much as the indelible image of the cowboy on the open range. In Cattle Kingdom: The Hidden History of the Cowboy West (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, $29), author Christopher Knowlton explores the true story behind the iconography by studying real-life examples of the cowboys and rancher-investors who shaped the world’s view of those men. His book takes both close-up and broad-angle views of the way the cattle industry molded the West. He makes the subject come alive, burnishing the image celebrated in fiction and film even while demonstrating his thesis: that the era of the great cattle drives didn’t just impact our view of American history, it also had a major effect on the economic and political landscapes of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The influx of cash from the East helped Western cities rise from the prairies, and the flood of beef from the West into the East changed the relationship between the frontier and “civilization.” But the boom didn’t last long.

Knowlton’s work posits that the characters and events featured in the brief, 20-year era of cattle barons and the open range have had an outsized influence on shaping our contemporary understanding of the history of the period. He relates in detail the stories of three investors from the Western boom — President Theodore Roosevelt, English aristocrat Moreton Frewen, and the outlandish Frenchman the Marquis de Mores — then takes a step back to offer a wider view of the ways in which the cattle industry influenced many other aspects of American history. The great Western cattle drives caused prairie boomtowns to spring up and collapse, brought wealth and political influence into the West, and offered young men a chance at adventure and income.

Knowlton also looks beyond those featured players at what it was like to be one of the tens of thousands of adventurous young men who rode the range, moving beef from Texas and the Southwest to the trains that would carry them to Chicago or St. Louis, and the great meat-packing plants and Eastern markets. He features the unlikely opera houses and splendid saloons that sprang up in Western boomtowns, considers the extermination of millions of bison, and examines the heartbreak of drought and winter die-off, painting an indelible picture of the era.

OF NOTE

Montana 1889: Indians, Cowboys, and Miners in the Year of Statehood by Ken Egan, Jr., (Riverbend, $22.99) is a worthy follow up to Egan’s previous volume of Montana history, Montana 1865. Following the same format as the earlier work, Egan time travels month-by-month through the momentous events of the year when the 25-year-old Montana Territory became the 41st state. He introduces famous and lesser-known Montanans, from Copper Kings to Chinese merchants to couples homesteading on the prairie. And he relates the stories of how the actions of men and women from different backgrounds came together to influence the future of the Treasure State. Egan’s ability to give weight to both the political machinations in Butte and family life in the Judith Basin makes this another history of Montana that is more than the sum of its parts. It is a valuable reflection on the state’s earliest days.

Montana 1889: Indians, Cowboys, and Miners in the Year of Statehood by Ken Egan, Jr., (Riverbend, $22.99) is a worthy follow up to Egan’s previous volume of Montana history, Montana 1865. Following the same format as the earlier work, Egan time travels month-by-month through the momentous events of the year when the 25-year-old Montana Territory became the 41st state. He introduces famous and lesser-known Montanans, from Copper Kings to Chinese merchants to couples homesteading on the prairie. And he relates the stories of how the actions of men and women from different backgrounds came together to influence the future of the Treasure State. Egan’s ability to give weight to both the political machinations in Butte and family life in the Judith Basin makes this another history of Montana that is more than the sum of its parts. It is a valuable reflection on the state’s earliest days.

In The Vengeance of Mothers: The Journals of Margaret Kelly & Molly McGill (St. Martin’s Press, $26.99), Jim Fergus continues the story he began in the highly regarded One Thousand White Women. In this inventive historical novel about a fictional and unofficial “Brides for Indians” program negotiated between President Ulysses S. Grant and the Northern Cheyenne leader Little Wolf in the 1870s, Fergus introduces new characters and reintroduces the contemporary historian and writer who is researching his family’s mysterious past. In his new book, Fergus picks up the story of the 1,000 women sent West to intermarry with the Northern Cheyenne, taking up his pen in the voice of Meggie Kelly and her twin sister, Susie, in late winter 1876. Fergus’s skill at writing in different voices and from different perspectives lends believability and continuity to his story. This is an absorbing read and worthy sequel.

In The Vengeance of Mothers: The Journals of Margaret Kelly & Molly McGill (St. Martin’s Press, $26.99), Jim Fergus continues the story he began in the highly regarded One Thousand White Women. In this inventive historical novel about a fictional and unofficial “Brides for Indians” program negotiated between President Ulysses S. Grant and the Northern Cheyenne leader Little Wolf in the 1870s, Fergus introduces new characters and reintroduces the contemporary historian and writer who is researching his family’s mysterious past. In his new book, Fergus picks up the story of the 1,000 women sent West to intermarry with the Northern Cheyenne, taking up his pen in the voice of Meggie Kelly and her twin sister, Susie, in late winter 1876. Fergus’s skill at writing in different voices and from different perspectives lends believability and continuity to his story. This is an absorbing read and worthy sequel.

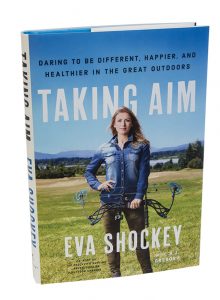

Women and girls with a passion for hunting and fishing will find inspiration in Taking Aim: Daring to be Different, Happier, and Healthier in the Great Outdoors by Eva Shockey (Convergent Books, $25). Shockey, who is not yet 30 years old, has earned a reputation as a highly skilled big game hunter. She is the first woman to be  featured on the front cover of Field & Stream in 30 years, and co-hosts, with her father, the TV show Jim Shockey’s Hunting Adventures. An avid conservationist and fitness enthusiast, Shockey acknowledges that her life has veered from the expected path. She reflects that, “As a little girl with dreams of becoming a ballerina, never would I have imagined that I’d be scaling rugged mountains and glassing deep valleys for a 1,500-pound bull moose.” At once self-deprecating and proud of her accomplishments, she has produced a relatable and entertaining memoir that makes readers wonder what she will take on next.

featured on the front cover of Field & Stream in 30 years, and co-hosts, with her father, the TV show Jim Shockey’s Hunting Adventures. An avid conservationist and fitness enthusiast, Shockey acknowledges that her life has veered from the expected path. She reflects that, “As a little girl with dreams of becoming a ballerina, never would I have imagined that I’d be scaling rugged mountains and glassing deep valleys for a 1,500-pound bull moose.” At once self-deprecating and proud of her accomplishments, she has produced a relatable and entertaining memoir that makes readers wonder what she will take on next.

Big Chicken: The Incredible Story of How Antibiotics Created Modern Agriculture and Changed the Way the World Eats (National Geographic, $27) offers author and journalist Maryn McKenna’s thoughtful research on the industry behind the tidy packages of meat that Americans purchase in huge quantities every year from supermarket shelves. McKenna, who is well known for her research on public health and public health policy, focuses this book on the use of antibiotics in the chicken industry. She argues that while the use of infection-fighting drugs has expanded the chicken industry, as a society we should consider whether the measures taken to produce disease-resistant, larger birds constitute a risk to human health or the environment. McKenna uses the ubiquitous chicken as an emblem of modern farming practices and mass food processing. She shares historical and cultural insights, and finally offers prescriptions for making food production safer and more sustainable in the future. She has the gift of making the scientific detail and political rhetoric in this thought-provoking book eminently readable and fascinating.

The new edition of the National Geographic Field Guide to the Birds of North America (National Geographic, $29.99) offers substantial updates to and improvements over the previous edition, making it the most up-to-date birding guide available. The National Geographic field guides have long been appreciated for offering identification tutorials and detailed illustrations, plus tips and clues to aid novices. Expert-level and more serious birders will appreciate the organization and scientific descriptions. This seventh edition includes 37 new species (the number of birds described in the book is more than 1,000), new illustrations and maps, and hundreds of updates to existing maps. It also conforms to taxonomic conventions established by the American Ornithological Society in 2016, and includes standardized banding codes.

No Comments