11 Dec History: Calamity Jane

Late one night in 1894, two men stopped outside a shack behind the old Grey Mule Saloon in Miles City, Montana. A middle-aged woman came out of the shack with a cheap suitcase and a “war bag,” a sack containing the remainder of her meager possessions.

The men would help her slink out of town. She owed the judge a $100 fine and didn’t have the money. It was all due to her “celebrity,” she told the men, and maybe things would be better in Deadwood, South Dakota.

As one man strapped her belongings to a horse, she said to the other, “You tell old Jackson, the [police] chief… he ought to be ashamed of himself. Do you know it took him and two more men to put me in jail?” Someday, she said, she would get her revenge.

But she never did. Actually, she never even made it to Deadwood. Instead, not long after leaving Miles City, she was living in a tent outside of Ekalaka, Montana.

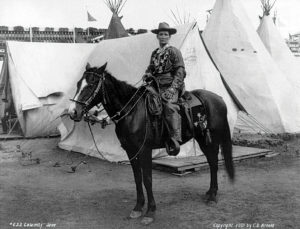

In 1901, Calamity Jane was photographed in Western garb in Buffalo, New York, while on tour to try to capitalize on her status.

It was just another wearying, dead-of-the-night installment in the episodic life of an alcoholic, poverty-stricken, functionally illiterate woman struggling to live by her values amid a degrading society. It’s of importance only because the woman, Martha Canary, was known as Calamity Jane, and her perception of her celebrity was spot-on. Indeed, of all the old-time Western idols, her story may have the most to tell us about our world today.

Since the 1870s, Canary has been perhaps America’s most famous cross-dresser. As a camp follower — maybe a prostitute — on an Army expedition into the Black Hills of South Dakota in 1875, the 19-year-old orphan started wearing military uniforms, not only because they were readily available, but also because they gave her the camouflage needed to spend more time with her soldier boyfriend.

The origins of Canary’s nickname are unclear. She claimed it was bestowed after her heroism amid calamities; some claimed she caused calamities. Other women of that era — most of them alcoholic prostitutes — were also called Calamity Jane; she simply became the most famous.

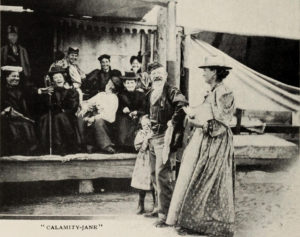

In his travelogue, first published in 1896, photographer Burton Holmes claimed that this woman at Larry’s Lunch Station in Yellowstone National Park was Calamity Jane.

Fame arose because journalists and then dime novelists could use the nickname and the cross-dressing to paint a vivid picture. Soon, dressing in men’s clothing became one of Calamity’s most recognizable characteristics. Indeed, her clothing has come to stand as a marker for feminism in general: Why should frontier women have been expected to behave differently than men? In a harsh environment requiring difficult physical labor, shouldn’t your frontier skills count more than the style of your clothing?

It’s a good question, though far from the dominant one in Canary’s life. In his definitive biography Calamity Jane: The Woman and the Legend, James McLaird finds much evidence that she often dressed as a female — when she could afford the clothes, when they wouldn’t hamper her activities, and when they wouldn’t lead to discrimination.

But those deeper questions fascinated the public. If you wanted to ask whether the clothes make the woman and whether they should, you could use Calamity’s legend alongside Joan of Arc and, later, Hillary Clinton. Thus, compared to other frontier figures like Annie Oakley or William F. “Buffalo Bill” Cody, who exemplified fascinating but increasingly quaint skills such as marksmanship or horsemanship, the Calamity legends have more contemporary resonance.

That’s especially true because today’s questions of gender-appropriate behaviors bleed into questions of sexuality and of gender itself. These questions drove Calamity’s fame in her own era: She wasn’t just a cross-dresser but also a gender-bender. She drank, swore, shot guns, and took risks like a man. This led to endless speculation as to whether she identified as a straight female.

Posing at Wild Bill Hickok’s gravesite in Deadwood, Dakota Territory, circa 1890s, was part of Calamity Jane’s false boasting about their relationship.

Again, McLaird’s evidence shows that the real-life Canary decidedly did. She rarely lacked male companionship; she often referred to her current guy as her husband. She bore two children, whom she loved. Her most common jobs were the then–female standards such as cook, waitress, and laundress.

But dime novelists could transform their fictional Calamity. They could portray her as coarsely vile, or as a conventional girl-next-door madly in love with a conventionally masculine figure such as Wild Bill Hickok. They could make her a career-long prostitute, flouting the sexual conventions of the time, or an amateur nurse, with a boundless well of female compassion. They could bestow upon her classic feminine beauty, which frontier conditions forced her to mask in public, or “inappropriately” masculine physical characteristics, suggesting hermaphroditism or even a spiritual ugliness.

Dime novels and other popular entertainment portrayed these conflicting versions of Calamity as if arguing about the meaning of gender. Indeed, in Deadwood Dick on Deck, with an estimated publication date of 1878, novelist Edward Lytton Wheeler has a character ask Calamity if she is female. She says yes, in the flesh, “but not in spirit o’ late years. Ye see, they kind o’ got matters discomfuddled w’en I was created, an’ I turned out to be a gal instead of a man, which I ought to hev been.”

Wheeler lacked today’s insights into transgender issues. For example, the characters in the novel, including Calamity herself, never really perceive her as male. At other points in the tale, Wheeler says that she has taken on certain male characteristics only as part of a quest to track down and kill the man who raped her. But the novelist’s portrayals suggest a deeper public fascination with gender issues — one that has only grown with their higher profile today.

In real life, Canary’s big struggle was not with gender, but with alcohol. Especially in the 1890s, after her son died in infancy and her daughter moved away, Calamity Jane usually was seen in saloons. The reminiscences and newspaper accounts span dozens of Montana communities: Utica and nearby Gilt Edge, Red Lodge and nearby Bridger, Livingston and nearby Horr and Aldridge, Big Timber, Billings, Helena, Butte, Miles City, and more. Often she insisted that men buy her drinks; sometimes she shot up the place with a revolver. When she had money, she’d be generous with it. But she often left town quickly, sometimes without paying her bills.

from Louis R. Freeman’s Down the Yellowstone, 1922, public domain.

Calamity was an alcoholic. Drinking changed her personality, generally for the worse. On some level she knew this, yet on another level she couldn’t stay away. Alcoholism was a common frontier affliction, but Calamity had a unique charisma that made her a memorable figure. Also, of course, she was world famous. When Canary stumbled into a bar, or when “Mrs. Dorsett” or “Mrs. Burke” was mentioned in a newspaper, she carried the baggage of her fictional counterpart.

Calamity Jane first appeared in a dime novel at age 19. Like Britney Spears, for example, she gained fame before she was mature enough to handle it. But unlike Spears, Calamity’s fame didn’t bring wealth or attorneys or shrinks or publicists. She lacked any tools to control how she was portrayed, or how she could come to grips with it.

How should she have responded? Does she reject the lies and the apparent status that fame brings? Or does she embrace the lies in hopes of making enough money to live on? And if so, what exactly is the vehicle to generate that money? Buffalo Bill could capitalize on fame because he was male, an extraordinary showman, and an organizational genius who managed a touring theatrical troupe. Canary was a poor, uneducated woman who frequently moved around a remote frontier, lacking even a fixed address.

In 1896, Calamity gave in and published an autobiography, which exaggerated some of her exploits. She claimed to have rescued a wounded Army captain and to have captured Hickok’s murderer. She carried around copies of the book to sell for 15 cents apiece, and she went on a tour of museums in the East, where she recited a memorized spiel about her life.

Her reputation paid a price. Braggadocio is almost expected from a high-profile warrior like Buffalo Bill — but how dare a woman tell stories both boastful and inaccurate about her own life? And why? It was unseemly for a woman to be so ambitious for fame.

Yet it’s not clear that she really wanted fame. Biographer McLaird shows that Canary’s most persistent and genuine characteristic was instead a desire for liberty. She wanted to be free to do what she damn well pleased.

She wanted to spend time with her boyfriend, even if that meant briefly wearing male soldier’s clothing. She wanted to have a rip-roaring time, even if that meant shooting a revolver inside a saloon. She wanted to be settled, married, and raising children. She wanted the privileges of being seen as married, and as a parent, even when she wasn’t married or actively parenting. She wanted to roam the West. Most of all, she wanted to get drunk.

Plenty of people today — and more in her era — would not find those goals to be worthy expressions of liberty. But the very point of liberty is that each of us can use it for our own purposes. And if the hero’s journey is to overcome obstacles toward a deeply felt goal, then Calamity Jane was a hero. If her purposes were a bit “discomfuddled,” the nature of her gigantic obstacles — sexism, gender issues, addiction, and the heartless cruelty of America’s celebrity-making machine — make her an especially vibrant hero for today.

John Clayton, a regular Big Sky Journal contributor, is the author of Natural Rivals: John Muir, Gifford Pinchot, and the Creation of America’s Public Lands, as well as Wonderlandscape, The Cowboy Girl, and other books; johnclaytonbooks.com.

Michael C Rosson

Posted at 23:39h, 02 FebruaryMartha Jane Canary was a woman before her time.