22 Nov Yellowstone High Country

“The nights were cold, and, if you woke up… you would hear the coyotes. … You could sit in the front of the cabin, lazy in the sun, and look across the valley. … You remembered the elk bugling. … You remembered how this country had looked when you first came into it … all the hunting and all the fishing and all the riding in the summer sun and the dust of the pack train, the silent riding in the hills in the sharp cold of fall going up after the cattle on the high range. … It’s a good country.”

In this excerpt from “The Clarks Fork Valley, Wyoming,” which ran in a 1939 issue of Vogue, author Ernest Hemingway was reminiscing. Written a year after his final stay, this essay contained his reflections on the five months he spent at the L-T Ranch in Wyoming, at the edge of Yellowstone National Park and close to the high-elevation community of Cooke City, Montana. Visiting first in 1930 at the suggestion of a friend, Hemingway soon found the ranch to be a retreat where he could write and avoid the outside world. It was a place, according to Robert Haskins, author of the article “Paradise Lost,” that was “as close [to paradise] as he ever found.”

During the summer months in Yellowstone High Country, near the Wyoming-Montana border, wildflowers cover the meadows below Pilot and Index peaks.

What Hemingway considered his summer home intermittently from 1930 through 1938, is now — more than 80 years later — my home; my family having acquired the L-T in 1964. And since my first visit in 1989, it has also been my escape: the place where I can find balance and peace. While much time has passed, amazingly — as Dave Dolese, a ranch hand who worked during Hemingway’s visits, said — “The L-T really hasn’t changed in lots of ways since the ‘30s. Of course, the [Beartooth] Highway affected the wildness, but it has continued to hold on to a lot of it. In the evening at sunset, we often marvel at how wonderfully empty the valley really is — a refuge from an often too-crowded world.”

Since my family’s arrival, cabins have been refurbished and modern amenities added; some paths have been paved and ATVs can often be heard on weekends. Yet, the same mountains soar above treeline, the sagebrush continues to grow uninhibited, and wildflowers delight every summer; grizzly bears still roam, the wind rustles the trees, and snow coats the landscape for a good portion of the year. The L-T, at its essence, remains unaltered and has become a place where I, a budding writer, have come to feel connected to nature, to the desire for remoteness, and to Hemingway himself, his spirit still present on this land, an inspiration to those who traverse it.

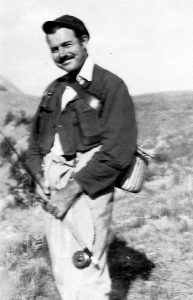

An avid angler, Ernest Hemingway spent many hours fishing the lakes and rivers around the Clarks Fork Valley.

This past summer while walking the property, I found myself veering toward one particular cabin. Its porch groaned underfoot as I reached for the antler door handle, above which hung a wooden plaque with the building’s name neatly etched. Each structure on the ranch has one: “Beartooth,” “Pilot,” “Dusk,” and this one, “Hemingway,” one of the cabins that the author called home during his stays.

Stepping inside, I could smell the scent of dust, sage, and wood permeating the air. Around the corner by the window sat a small desk, battered with time. While we have no proof that this is the exact “scarred, wooden school desk” Hemingway used, it’s unquestionable that he had worked within these walls. As Dolese recalled, “Ernest was busy most of the time writing in his cabin.” In this very cabin for much of his time on the ranch, and also in one other that has since been moved.

During Hemingway’s first stint here, which spanned four months, he wrote much of Death in the Afternoon, and from where I stood, I could imagine the sound of the keys hitting the paper. During his second stay two years later, he sat in this spot to work on The Light of the World and write letters to critics. And on later visits, it was here that he finished To Have and Have Not and his only full-length play, The Fifth Column, which was included in the 1938 anthology titled The Fifth Column and the First Forty-Nine Stories.

I pulled the chair out from under the desk and nestled in. Rather than a typewriter, a laptop sat before me, its screen a glowing beacon of technology in an otherwise frontier-like room. I opened a book by my late grandfather, A History (more or less) of the RDS, B-4, L-T, and Hancock Ranches, and began researching, emerging only when distracted by the views or the sounds of a bird call, interruptions I imagined that Hemingway, too, must have encountered.

Despite highways and other modernizations, the views of Pilot and Index mountains remain unchanged overtime.

Through my research that day, I learned that Hemingway loved spending time outdoors and was known to be an avid fisherman. According to Polly Copeland — whose family helped financially support the ranch and frequently visited — Hemingway had a “great sporting passion … always back with marvelous tales about the size and number caught and released, and the whoppers that got away.” By September of his first visit, he’d pulled in more than 100 trout, claiming the Clarks Fork River to be the best fishing in the world. Using Hardy tackle, and notably tying three flies to his leader, he waded for hours. “The native trout were sleek, shining, and heavy, and nearly all of them leaped when they took the fly,” he wrote in Vogue.

I smiled, knowing that I’ve stood, at times knee-deep, along the very same stretches of river. While I tied on just one fly, I pictured Hemingway, instead, deftly securing each of his many to the line on his outdated rod. I could imagine the current picking up the line and the rod straining under the weight of a fish, a flash of white breaking through the surface and each spin of the reel bringing the trout closer.

Reading page after page, I saw the similarities between his experiences within the valley and my own. The author spent time at Granite Lake, as had I. We’d both wandered along Crandall Creek and fished the Broadwaters, hoping to catch the day’s largest trout. He may have arrived on horseback while I hiked; he might have stayed for days, while I spent only a few hours. But the same trees still run along the shoreline, the same blue water flows over weathered river rocks. It seemed that he and I had spent much of our time exploring, adventuring, and appreciating the same land.

Further reading revealed Hemingway’s various hunting expeditions for elk, bear, and other animals. One such outing brought him up and around Pilot Peak, a mountain that, according to Haskins, “When he looked out the window or stood in the door [of his cabin] … dominated his view.”

Chasing bighorn sheep at nearly 10,000 feet on loose rock proved both challenging and spectacular for Hemingway. “You sat in the sun and marveled at the formal, clean-lined shape mountains can have at a distance, so that you remember them in the shapes they show from far away, and not as the broken rockslides you crossed, the jagged edges you pulled up by, and the narrow shelves you sweated along, afraid to look down,” he wrote in Vogue. I could imagine these cliffs, the scree, and the fear he must have felt, for I too have clamored to this location, witnessing both the grandeur the scenery evokes and the athleticism it demands to get there. Hemingway said it best in a letter to his friend Mike Strater: “Damnedest ledge work you ever saw … for about 2 miles on a rockslide. Fell 9 times.”

In my experience, outcroppings required rerouting, and slips cost us valuable progress, marring our skin in the process. And yet we continued, toward the saddle between Pilot and Index, the peaks losing their telltale form but not their magnitude as we neared. Even with haze from nearby forest fires, the views encompassed the entire Upper Clarks Fork Valley, and the peaks of the Absarokas and Beartooths encircled us, as if congratulating us on the feat achieved by only a handful of my family members, and also, of course, by Hemingway.

Moved by the experiences he had in the valley, Hemingway wove memories of this land into many of his famous works, memorializing the L-T as a place for both writing and inspiration. His novel True at First Light, released posthumously in 1999, recounts one of his bear hunts and compares a Kenyan village to Cooke City, the town nearest to the L-T. The two bars in Hemingway’s short story, “A Man of the World,” are called The Pilot and The Index, a direct reference to the mountains that hover behind Cooke. And in “The Snows of Kilimanjaro,” the death of a ranch boy parallels the murder of Jim Smith, a valley homesteader who was killed at the L-T in 1912.

In For Whom the Bell Tolls, perhaps one of the novelist’s most famous books, the main character, Jordan, hails from Red Lodge, Montana, which is located near Cooke City. His frequent flashbacks to his life out West also stem directly from much of what Hemingway experienced in the mountains surrounding the ranch. Even when trying to avoid losing consciousness, Jordan tells himself to “think about Montana.” As stated by Chris Warren in his book Ernest Hemingway in the Yellowstone High Country, “While [Hemingway] never wrote a novel about the American West, For Whom the Bell Tolls shows the importance of the Yellowstone High Country in his work.”

However, other than the article for Vogue, Hemingway never wrote specifically about the Yellowstone High Country or the Upper Clarks Fork Valley. No novel. No short story. Nothing. I wondered why, when his memories worked their way into numerous pieces, he never crafted one solely dedicated to his time in the West. In “The Snows of Kilimanjaro,” perhaps Hemingway used the character of Harry to grapple with this very question:

“But what about the rest that he had never written? What about the ranch and the silvered gray of the sage brush, the quick, clear water in the irrigation ditches, and the heavy green of the alfalfa? The trail went up into the hills and the cattle in the summer were shy as deer. The bawling and the steady noise and slow-moving mass raising dust as you brought them down in the fall. And behind the mountains, the clear sharpness of the peak in the evening light and, riding down along the trail in the moonlight, bright across the valley. … Now he remembered coming down through the timber in the dark holding the horse’s tail when you could not see and all the stories that he meant to write … he knew at least twenty good stories from out there and he’d never written one, why?”

The author, Alison McClure, often fishes the same stretches of the Clarks Fork River that Hemingway used to frequent. In her research, she discovered that she and the infamous writer have shared many of the same outdoor experiences in the valley.

Did Hemingway wish he’d written more about his time in this valley? As an owner of the L-T today, is my purpose to now take inspiration from this land and turn it into my own creations?

Interestingly, when asked about his day of fishing, Hemingway typically recounted that it was just okay, despite his successes. Perhaps in his well-chosen words, be they written or spoken, Hemingway sought to spark interest without offering full access, to hold the land’s full greatness a secret as a means of protecting its beauty and remoteness. And so, perhaps I too will leave it at just this one story in hopes of preserving the valley’s wildness for generations to come.

No Comments