23 Jul Images of the West: Trains of Discovery

IN THE BEGINNING, RAILROADS were among the first to practice what environmentalists today would call restraint. In any comparison between highways and airports, railroads are the most resistant to unplanned change. Highways bring change regardless — shopping centers, subdivisions, strip malls, auto dealerships, billboards, junkyards, and much more. No railroad wished that for that landscape because no railroad could control it. An efficient railroad needs to limit stops; sprawl defies a railroad’s need for compact development. Nor was the clutter that became roadside America something the railroads could hope to sell. Even as they opened the national parks to tourism, they were concerned about protecting the scenery along the way. The tourist buying a railroad ticket to a national park was also committing to several days on the train. Every landscape weighed down by unexpected ugliness would only disquiet passengers.

In effect, the railroads were practicing environmentalists a century before the term was popularized. This is also to explain why organized preservationists turned to the railroads in asking Congress for a “Bureau of National Parks.” A national parks bureau, the railroads agreed in 1910, was needed to support their own investments in the parks. Those investments had indeed proved substantial, including roads, trails, and hotels. Approved in 1916 as the National Park Service, the agency was exactly what the railroads wanted, promising that the government would finally pay for the infrastructure and allow the railroads to concentrate on attracting passengers.

The sobering realization is how quickly the fortunes of the railroads — and the landscape — changed. In 1929, a daily average of 20,000 intercity passenger trains operated in the United States. By 1960, the number had fallen to 5,000; in 1970, just 400 trains survived. On its inauguration in 1971, Amtrak halved those survivors yet again, further insisting that the future of the passenger train was primarily in urban corridors.

THE NORTHERN PACIFIC RAILWAY

Yellowstone Park Line

The traveler who has journeyed eastward to climb the castled crags of Rhineland and survey the mighty peaks and wondrous glaciers of the Alps, who has … gazed upon the marvelous creations of Michelangelo and da Vinci; and stood within the shadow of the pyramids — may well turn westward to view the greater wonders of his own land. Beyond the Great Lakes, far from the hum of New England factories, far from the busy throngs of Broadway, from the smoke and grime of iron cities, and the dull, prosaic life of many another Eastern town, lies a region which may justly be designated the Wonderland of the World.

—Charles S. Fee, General Passenger Agent, Northern Pacific Railroad, 1885

When Americans think of conservation, they inevitably think first of the national parks. Although conservation comes in many forms, it is the parks that speak to idealism. Accordingly, that America’s idealism received a crucial boost from industry may seem almost sacrilegious. Allegedly, the explorers of 1870 originated the national park idea while in the process of opening Yellowstone. The point is that even their altruism had its limits. Yellowstone National Park did not grow in the mind of Congress until the intervention of Jay Cooke, who as the financier of the Northern Pacific Railroad (later to be named the Northern Pacific Railway) hoped to profit from Yellowstone as a great resort.

Simply, legend links Yellowstone to its explorers because their account sounds patriotic. No robber baron aided the national park idea; after all, a national park should be unselfish. America’s heroes remain the men of the so-called Washburn Expedition, who, before departing Yellowstone, recapped their findings around what became known as “the Yellowstone Campfire.” It was the night of September 19, 1870. Since entering Yellowstone in late August, they had seen the Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone, Yellowstone Lake, and the Upper Geyser Basin. Those wonders were then central to their discussion. Why not simply claim them, the men advised one another? By filing with the government land office for the choicest wonders, every explorer could reap a share of Yellowstone. At that point, Cornelius Hedges, a young lawyer from Helena, Montana, allegedly disagreed. The men should reject any notion of profit, he scolded, and instead promote Yellowstone as a great national park. Nathaniel Pitt Langford, the celebrated publicist of the expedition, then recorded in his diary: “His suggestion met with an instantaneous and favorable response from all — except one — of the members of our party, and each hour since the matter was first broached, our enthusiasm has increased.” Thus Langford concluded his entry for September 20, “I lay awake half of last night thinking about it; and if my wakefulness deprived my bed-fellow (Hedges) of any sleep, he has only himself and his disturbing National Park proposition to answer for it.”

The nagging question still is accuracy. Langford did not publish his diary until 1905, fully 35 years after the event. There probably was a campfire, although not the campfire Langford waited 35 years to describe. Embellishments would have been hard to resist, and certainly he edited everything for publication. Nor did the other men around that campfire — half of them also major activists, including Henry Dana Washburn — mention the national park idea in their writings or public speeches during the months that immediately followed.

The missing names are the most telling ones, principally Jay Cooke as promoter of the Northern Pacific Railroad and his office manager, A. B. Nettleton. Indeed, the explorers’ campfire discussion that mid-September evening could not have taken place in ignorance of the railroad’s plans. Just three months earlier, Cooke had invited Langford to his estate outside Philadelphia. Not only did Cooke retain Langford to promote the railroad, he likely suggested the Washburn Expedition as the means. Langford then carried Cooke’s idea back to Washburn, whose position as Montana’s surveyor general invited that he be elected to head the party. Throughout, Cooke was the one anticipating the opportunity, namely, that his right-of-way across southern Montana would bring him within 50 miles of Yellowstone. Although runner-up to the Union Pacific Railroad, completed in 1869, the Northern Pacific would be the only transcontinental railroad controlling this grandest of natural treasures. Every prospective traveler (and Yellowstone promised many) would be in the railroad’s grip.

Consequently, in part fulfilling his obligations to Jay Cooke, Langford returned east after the expedition to deliver a series of public lectures. Only the Northern Pacific Railroad, he noted, would make Yellowstone “speedily accessible” to tourists. Of course, that is exactly what Cooke had paid him to say.

A re-enactment of Washburn-Langford camp and “the Yellowstone Campfire” where discussions about the future of the Yellowstone went from privatization to promoting it as the first national park. NPS photosMeanwhile, the Washburn Expedition had hardly been a systematic exploration, nor had professional scientists been included. That opportunity awaited Ferdinand V. Hayden, a distinguished geologist at the University of Pennsylvania and one of the country’s most reputable government surveyors. When Langford’s tour brought him to Washington, D.C., Hayden attended his lecture. On the spot, an intrigued Hayden made Yellowstone his priority. Congress agreed and appropriated $40,000, allowing the geologist, as he had hoped, to lead his follow-up expedition during the summer of 1871.

No less aware of that opportunity, Jay Cooke again intervened, this time in a letter from A. B. Nettleton asking whether Thomas Moran might join the group. … Cooke then loaned Moran $500 to make the trip. Better than any lecture or newspaper article, Moran’s paintings would bring Yellowstone alive. His field sketches and color studies indeed formed the basis of later efforts to inform the Congress. Moran followed that display in the Capitol rotunda with his masterpiece, The Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone, completed in June 1872. A whopping 7 by 12 feet, it commanded $10,000 from Congress, which hung it in the Senate gallery. Obviously, Moran had no trouble repaying Cooke his loan.

In short, the railroad was still guiding events. As of September 1871, even as the Hayden Survey departed Yellowstone — and despite the comments in Langford’s diary — no visible park campaign had emerged. Langford and his colleagues might at least have mentioned their park idea in the wake of the Hayden Survey. Yet no one came forward, not even Hayden, until Jay Cooke made a final intervention. …

Having secured the influence of Ferdinand Hayden, railroad officials stayed out of the limelight. In coming years, most railroad executives would do the same. Always suspicious of corporations, the public might easily misinterpret their advocacy as interference. For achieving Yellowstone, Hayden’s fame and reputation should be enough. Indeed, his invited report to Congress did just as the railroad hoped, lending a sense of urgency to the legislation. Claimants had already descended on Yellowstone, Hayden noted, intending “to fence in these rare wonders so as to charge visitors a fee, as is now done at Niagara Falls, for the sight of that which ought to be as free as the air or water.” Absent congressional intervention, “decorations more beautiful than human art ever conceived” would be despoiled “beyond recovery.” The time for action was now. Jay Cooke and his associates still quietly celebrated when on March 1, 1872, President Ulysses S. Grant signed the Yellowstone park bill into law.

Unfortunately for Cooke, the next several years proved bittersweet. Crushed by the financial collapse of 1873, his personal interests in the Northern Pacific failed. Delayed further by the lingering Depression, the railroad was not completed until 1883. Others then received the honor of opening the spur track south from Livingston, Mont., to the gates of Yellowstone National Park. Regardless, both Cooke and A. B. Nettleton had secured their place in history. Aware that Congress needed prodding, they had made sure it came in time.

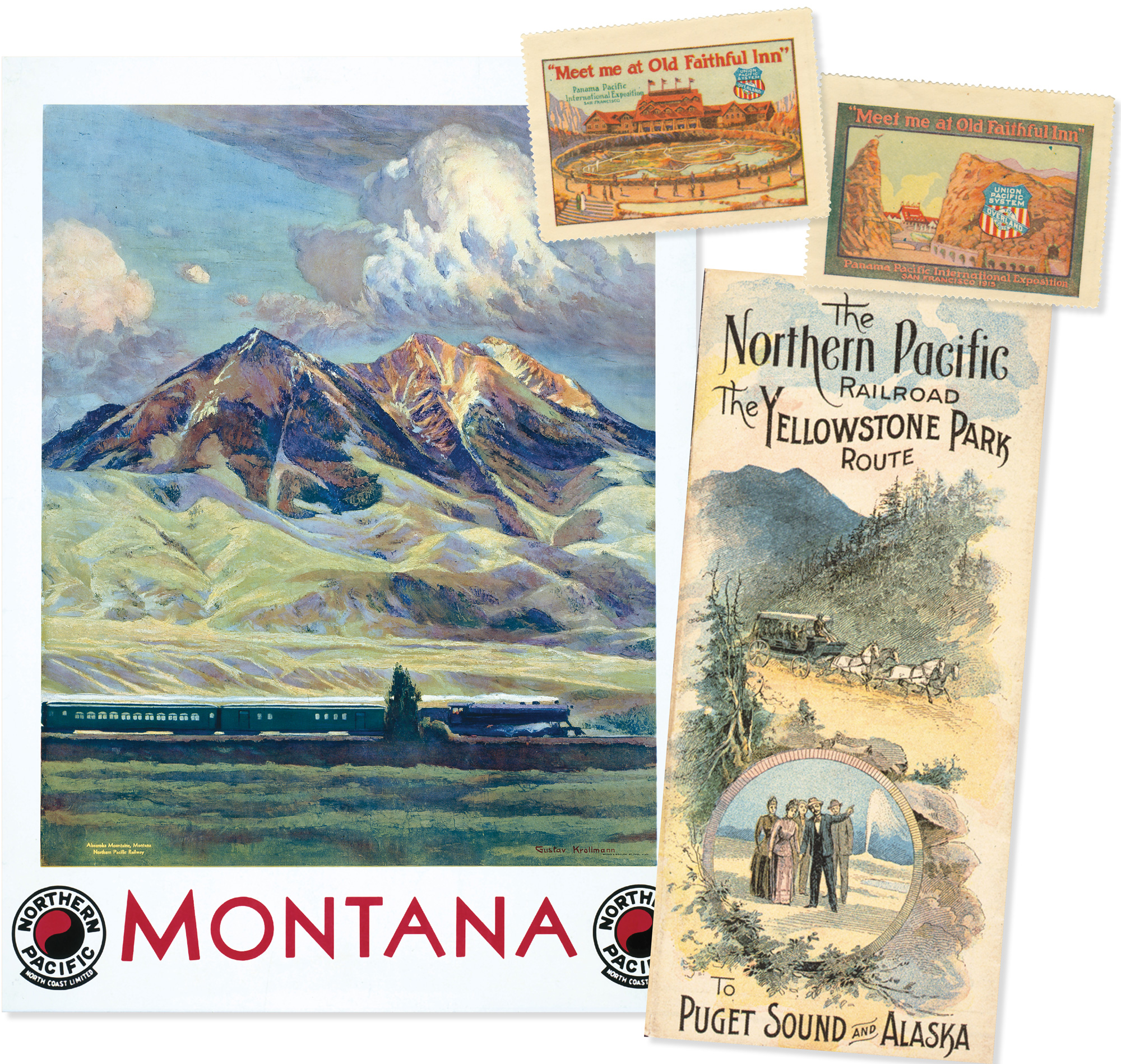

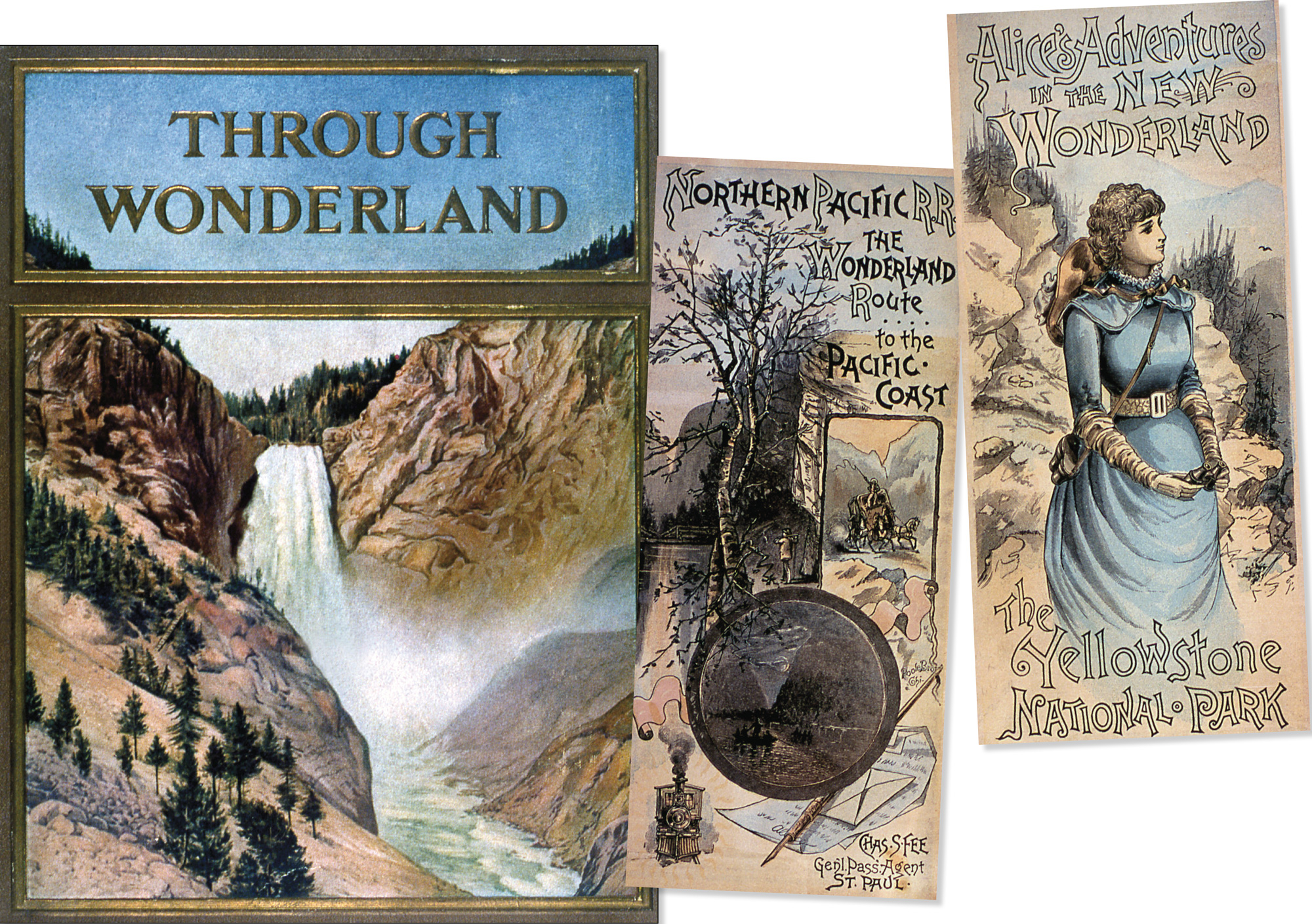

One thing had not changed. Turning finally to the promotion of Yellowstone, the railroad obviously still hoped to build a monopoly, anchored by investors and subcontractors with strong ties to the railroad proper. However, Yellowstone was still a national park. When everyone’s zeal got out of hand, the government intervened. The Northern Pacific then quietly made amends through its new passenger agent, Charles S. Fee. Inspired by the supernatural descriptions of Yellowstone, Fee chose Lewis Carroll’s popular story Alice in Wonderland as the perfect advertising theme: Wonderland! The name further suggested the title for an annual guidebook, beginning with Fee’s personal compilation, Northern Pacific Railroad: The Wonderland Route to the Pacific Coast, 1885.

Further distancing the railroad from earlier attempts to exploit the park, Fee pledged the Northern Pacific to preservation. “We do not want to see the Falls of the Yellowstone driving the looms of a cotton factory, or the great geysers boiling pork for some gigantic packing-house,” he wrote, “but in all the native majesty and grandeur in which they appear to-day, without, as yet, a single trace of that adornment which is desecration, that improvement which is equivalent to ruin, or that utilization which means utter destruction.” In 1893, the railroad sealed his words with a new logo, the Chinese oval for yin and yang (the balanced universe). A banner curved across the bottom added the proclamation “Yellowstone Park Line.”

Next came a restructuring and a name change. Now as the Northern Pacific Railway, the line eventually faced serious competition. Arriving at West Yellowstone for the season of 1908, a subsidiary of the Union Pacific Railroad ended the Northern Pacific’s 25-year monopoly. In anticipation, the Northern Pacific was already fighting back. From 1883 to 1902, access had centered on Cinnabar, Mont., several miles north of the park. Coordinating with the construction of Old Faithful Inn (1903–1904), the Northern Pacific extended its tracks to a new depot at Gardiner, immediately adjacent to the boundary proper. A fitting companion to the inn, the Gardiner depot itself combined rustic logs and vaulted ceilings into a magical park preamble. Gateway Arch, dedicated in 1903 by President Theodore Roosevelt, lay just 100 yards up the hill. From there, it was only five miles by stagecoach to Mammoth Hot Springs, where the National Hotel, an original building from 1883, welcomed arriving guests to the Yellowstone tour.

It would have been surprising had the competition ended there. Five railroads would ultimately serve the park, all following the advice of Frederick Billings. As president of the Northern Pacific in the mid-1880s, Billings cautioned that its entire right-of-way should appeal to passengers, or again, why would people want to come to Yellowstone? In that spirit, all of the Yellowstone River Valley should be protected as the glorious foreground of the national park.

Rarely had a technology more genuinely led to the saving of landscape, if initially because the landscape appealed to tourists. The result was no less effective, whether inside the national parks or out. It remains the distinction of railroads to this day. Although needing the land, railroads rarely gobble it. So it was that a sliver of railroad laid itself across Montana, forever to be remembered as the “Yellowstone Park Line.”

The tracks leading directly to Yellowstone have long been abandoned. All that remains of the era of train travel are some of the historic hotels built by the Northern Pacific Railway and, at West Yellowstone, the Union Pacific Railroad’s magnificent dining lodge (1925) and passenger depot (1909), now anchoring the West Yellowstone Historic District and museum complex. Yet at Glacier National Park the tradition continues with daily rail passenger service.

GLACIER NATIONAL PARK—MONTANA

The Roof of the Continent

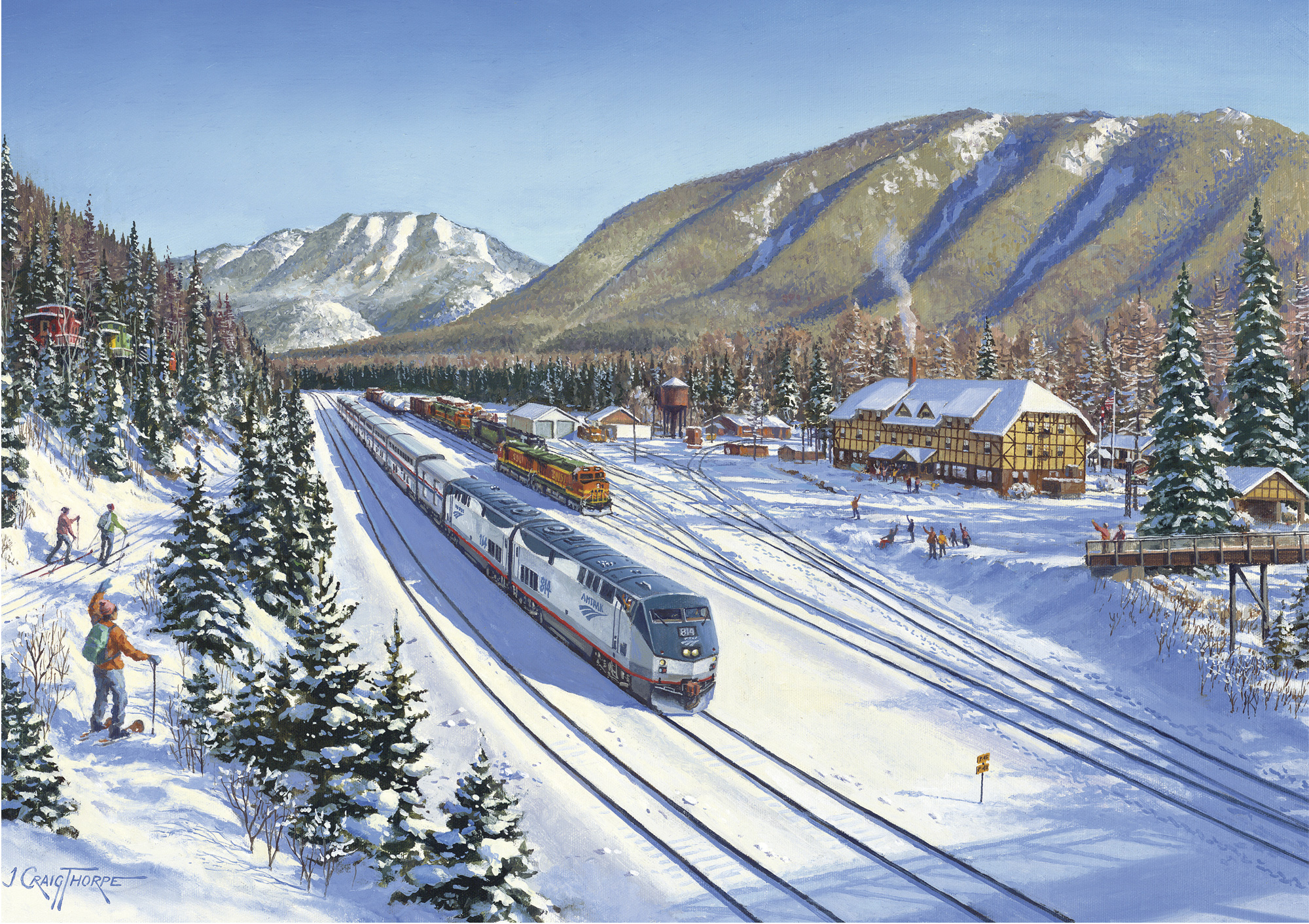

If there is such a thing as time travel, then the Empire Builder to Glacier National Park is the quintessential time machine. The moment you arrive, it is as if your train has lost a century. The mood is grandly pronounced at East Glacier Park Station, where, directly opposite, the historic Glacier Park Lodge envelops the crest of a long, gentle incline. A pathway lined with flower beds escorts visitors to the door. Entering the lobby, the first-time guest stands transfixed. Cathedral-like, the space towers from floor to ceiling, ribbed everywhere with massive logs. Adding another touch of historical ambiance, original paintings grace the walls.

It all began with the railroad, still literally at Glacier’s door. Certainly, no track in America is more distinctive. Never having lost its rail passenger service, Glacier retains the heartwarming sense it has a threshold. Although a major highway serves the park, it is the railroad that says continuity. Ever deeper into the heart of the wilderness, paralleling Glacier for more than 50 miles, the Empire Builder continues to brook no rivals for marking the flow of time and history.

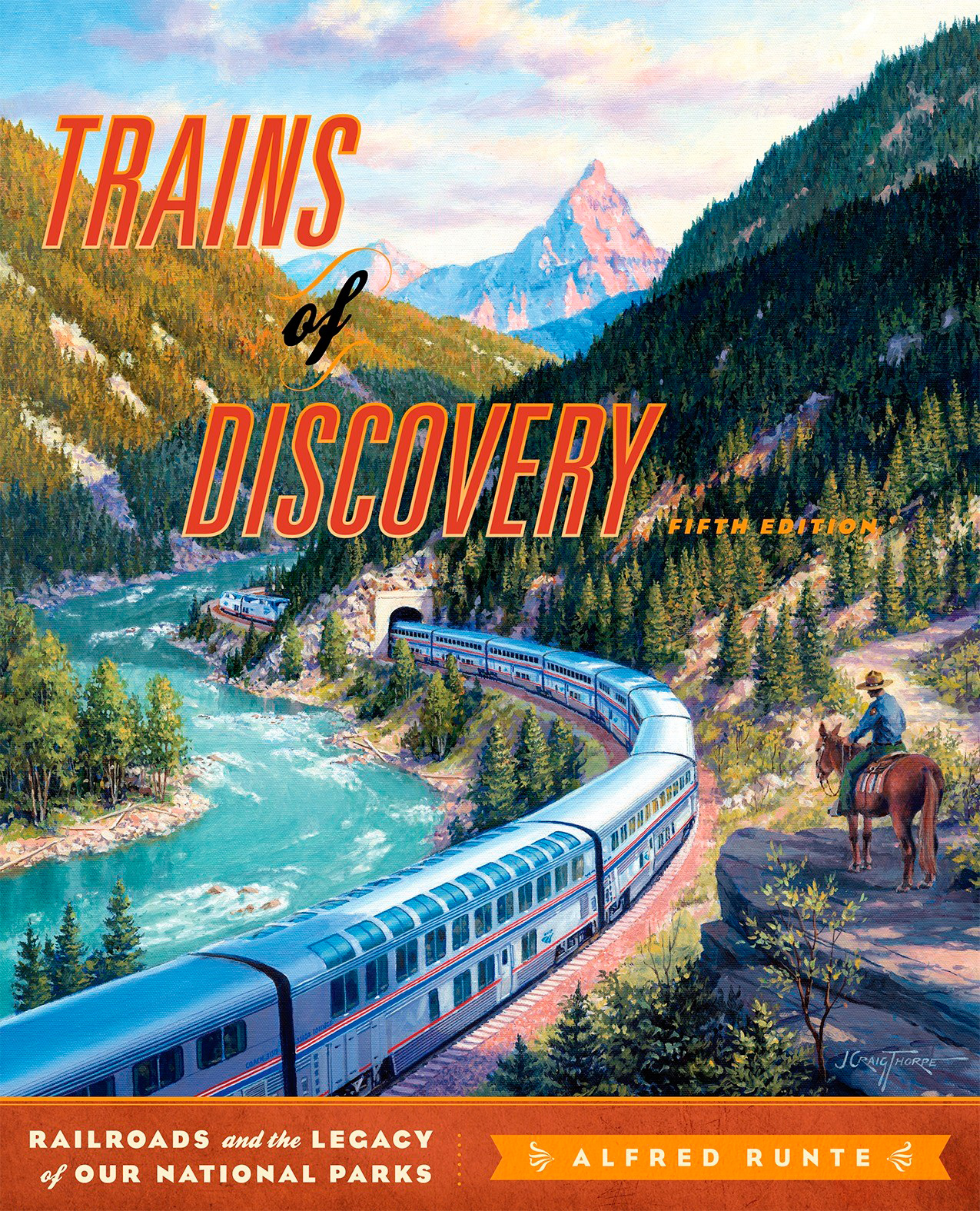

Editor’s Note: This is an excerpt from the recently released book, Trains of Discovery: Railroads and the Legacy of Our National Parks, by historian Alfred Runte (Roberts Rinehart Publishers, 2011).

- Courtesy of Roberts Rinehart Publishers

- Northern Pacific Railway ad campaigns promised adventure and wide open country on the Yellowstone Park Route in the early 1900’s. This poster (1930) by Gustav Krollmann depicts the Yellowstone Comet southbound for Gardiner through Paradise Valley.

- Nathaniel P. Langford of the 1870 Washburn, Langford, Doane expedition. NPS photos

- A re-enactment of Washburn-Langford camp and “the Yellowstone Campfire” where discussions about the future of the Yellowstone went from privatization to promoting it as the first national park. NPS photos

- Hayden Geological Survey Expedition members at Firehole Basin; both photos by William H. Jackson; 1872. NPS photos

- Ferdinand Hayden leader of the Hayden survey of 1871. The railroad executives hoped Hayden’s fame and reputation might add credibility to Yellowstone becoming a national park. NPS photos

- Partners in preservation by J. Craig Thorpe, commisssioned by the Izaac Walton Inn. Photo courtesy Roberts Rinehart Publishers

- In 1934 passengers prepare to board the westbound Empire Builder at the East Glacier Park station.

- Beginning seasonally in the summer of 1913, the Great Northern added open observation cars to its trains passing through Glacier National Park. Photos courtesy Roberts Rinehart Publishers

No Comments