30 May The Overlooked Second Chapter

Ask any author, historian, or cowboy with an eye for the great Old West, and they’ll credit Dick and Dora Randall as the heart and soul of the OTO, Montana’s first dude ranch. Situated along Cedar Creek in the Absaroka Mountains, 10 miles from the north entrance to Yellowstone National Park, the OTO is a picturesque example of the dude ranch paradigm and is listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

As visionaries with carny mentalites, the Randalls founded the ranch in 1898. They began attracting city folk from Boston, Chicago, and even Europe to come to a mountainous Montana ranch and enjoy an authentic, yet temporary, cowboy lifestyle.

The OTO dude ranch experience included riding, roping, relaxing, and pack trips into Yellowstone National Park. | Courtesy of the Libbey Family

The ranch legacy lives on today despite ownership changes that eventually led the U.S. Forest Service to acquire the property from the Rocky Mountain Elk Foundation in the 1990s. For three decades, the U.S. Forest Service has stewarded modern preservation efforts at the ranch, and last year, the agency partnered with True Ranch Collection to host guests for the first time in 80 years as part of a pop-up ranch stay that generated funds to restore the site further.

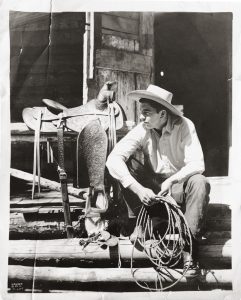

When Chan and Mary Libbey (pictured) bought the OTO in 1934, they envisioned continuing the dude experience of the previous owners, Dick and Dora Randall. | Courtesy of the Libbey Family

The original OTO “dude” experience of the late 1800s and early 1900s included horseback riding steep trails, packing into Yellowstone National Park for hunting and fishing, learning to rope, and simply enjoying the open range from the Big House porch. It was defined by true Western accommodations and hospitality — all for about $50 to $90 a week.

For “Pretty Dick” Randall, it was quite the celebrated — almost legendary — life wherever he traveled, culminating with sharing the podium with President Roosevelt at Yellowstone National Park’s arch dedication in Gardiner in 1903.

A mere 10 miles from Yellowstone National Park, the property consisted of 3,500 acres to ride and roam. | Courtesy of the Libbey Family

Eventually, though, as things go, Dick and Dora began to feel their age, and the days of actively attracting dudes to Cedar Creek began to take a toll. By the early 1930s, the ranch was showing its years as well, needing many renovations, roof repairs, and the installment of a new convenience: indoor plumbing. Thanks to the Depression, 1931 was the OTO’s worst year, forcing some family members to work at Yellowstone’s Old Faithful Inn for summer employment.

Fortunately for the Randalls, Chan T. Libbey arrived. A tall, introverted, 21-year-old man of great inheritance, Libbey had visited the OTO three times during the previous decade. He was a buttoned-down New Englander with a smile, checkbook, and blind willingness to take what the Randalls had accomplished and improve it. Libbey, along with his wife, Mary, was made for Montana: hardworking, resilient, and — while not an astute businessman — enthusiastic about the possibilities of the 3,500 acres.

So, after sharing ownership with the Randalls’ son for a year, Libbey became the sole proprietor of the OTO in 1934, paying $100,000 for the land, buildings, 160 horses, and 30 cows.

Thus began the second chapter of the OTO dude ranch: a confluence of contradictions. Or described even more succinctly today by son Chan Libbey II — one of the last remaining Libbeys from that era — “Well, it just didn’t go as planned.”

NEW FURNITURE AND A NEW ATTITUDE

Less has been written about this period of the OTO than any other. So, if you’re going to start writing, why not start with the furniture?

“The first thing my pop said was, ‘We need new furniture.’ That’s the way Dad was,” recalls Chan II or “Channie,” who, at age 86, sits on a turquoise Molesworth chair in his home in Paradise Valley.

The new owner undoubtedly wanted to make people comfortable, so he set off to upgrade the OTO. New furniture was made. Buildings and roofs were repaired. The large shingle house was built. Technologies such as copper plumbing and fixtures were incorporated and generators were installed. New, experienced employees were added to the staff of old-timers. Libbey even began buying Arabian horses from California to impress all who came, and he endeavored to breed a heartier stock for the rough mountains lining Paradise Valley.

Despite all his efforts, Libbey is widely remembered today for the furniture, his most immediate and lasting contribution to the OTO’s legacy, which was handmade by Thomas Molesworth of Cody, Wyoming. Durable and overbuilt, with burls, leather fringes, and Western motifs, these pieces refined OTO’s rustic, authentic decor.

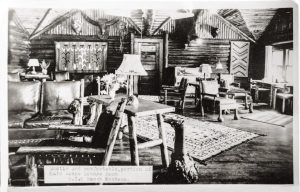

The Big House at the OTO featured an inviting selection of burled Molesworth furniture. | Courtesy of the Libbey Family

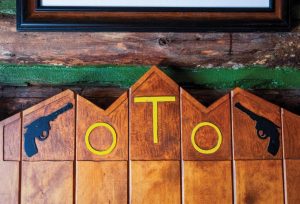

Outfitting the OTO was one of Molesworth’s first major commissions, and the furniture maker quickly became friends with Libbey as his Shoshone Furniture Company started turning out more of the sturdy, Western-themed tables, chairs, and beds. OTO patrons enjoyed the cushy sofas in the Big House, seated among bear, elk, and game bird mounts. They slept in beds with headboards featuring carvings of pistols and the OTO brand.

This Molesworth bed headboard was made for the Libbeys in the ‘30s. | Photo by Jeff Moore

The alliance was so strong that Molesworth asked Libbey if he wanted to invest in his company as it expanded and acquired more prominent clients, such as the Northern Hotel in Billings and Coca-Cola’s Robert Woodruff’s Trails End Ranch in Cody. Libbey provided the funds, but later regretted not getting a piece of the company.

“Molesworth speaks to the West, and his success was making comfortable furniture,” says Terry Winchell, author of Molesworth: The Pioneer of Western Design and owner of Fighting Bear Antiques in Jackson, Wyoming. “Bigger than that, though, he did not just sell furniture. He sold roomscapes, which meant he also sold Native American rugs and artifacts to his clients. So, an Easterner dude coming to the OTO really experienced that feeling of the West, just as Teddy Roosevelt probably did when he stayed there.”

Chan and Mary Libbey saddled up in front of the Big House at the OTO. During their ownership, the property transitioned from a dude ranch to a working cattle and horse operation. | Courtesy of the Libbey Family

DUDES NO MORE

According to the Dude Ranchers’ Association, dude ranching’s heyday occurred during the Roaring ’20s. Yet, as Chan and Mary Libbey took the reins of the OTO in 1934, the Depression had already affected their business. Despite its notoriety, renovations, new furniture, and promotions, dude visits became less and less frequent. Certainly not as flamboyant or creative as his predecessor, Libbey, with his early lack of business acumen, ran the OTO at a loss for the remainder of the decade.

Historians note that 1939 was the last recorded year of dude guests at the OTO. All the new makeovers were frozen in time as the Libbeys transitioned the dude ranch into a working cattle and horse operation. That is until unforeseen events interrupted even those dreams.

In 1943, just four years after the transition, while living with Mary and their two kids in Livingston, Libbey received the final nail in the OTO: a draft letter. His son recalls that Libbey facetiously said, “I must have a friend at the draft board ’cause they don’t want too many 30-year-olds.”

For two years, Libbey served in Europe as a radio field operator. More important than how he entered World War II was how he returned to Montana. His son says he was never the same. “Shell-shocked” was the diagnosis of the era; today, it’s known as PTSD. As soon as Libbey walked through the door of his Livingston home in 1945, his family knew it would be a long recovery. “When he did come back, he spent a lot of time up at the ranch,” Channie says. “But he was shell-shocked, depressed, and endured shock treatments. So interest waned.”

The OTO pool room, in particular, was always a popular attraction at the end of the day. | COURTESY OF U.S. FOREST SERVICE AND THE LIBBEY FAMILY

Adding to the drama, a mountain slide and flood took out the bridge behind the Big House and ruined the barn; desire to reboot the dude ranch was forever gone. With all the energy finally knocked out of him, Libbey looked for a new owner. And, in 1946, he found a Mrs. Jesse Shields of Columbus, Montana, who bought the ranch in 1949, ending the Libbey Era and Montana’s prime dude ranching experience for good. From there, a series of sales led the property into the ownership of the U.S. Forest Service, which remains the owner today.

THE LEGACY OR LAMENT

According to Jaye Wells of Tuscon’s True Ranch Hospitality, a former preservation architect who has worked on restoration at the OTO, “The Libbey story is often ignored compared to the Randalls’. Theirs was a hard act to follow.”

“I think it’s a little unfair,” he adds. “When the people did the historic application [for listing on the National Register of Historic Places], they were all about Dick Randall. It’s a shame they cut off the historic time in 1934, when he sold it. One of my goals is to get the register amended so it includes everything through 1939.”

By all accounts, Chan and Mary Libbey came to OTO at the ideal time, and their vision was not short-sighted. They added hallmarks of American craftsmanship and art, and provided fundamental preservation efforts that kept these buildings standing today, all while running a dude ranch during a

tumultuous era.

Like any cowboy, Chan T. Libbey came to the OTO with dreams. Unfortunately, the dream of running a successful dude ranch was, at least in part, overrun by world events. | Courtesy of the Libbey Family

Still, fingers of failure often point at the man himself. Sometimes, good intentions cannot overcome youth and business inexperience. It’s an accusation that Chandra, Channie’s sister, took a resounding exception to in the summer of 1994. In a spirited response to a Livingston Enterprise article on the Randalls’ reign, she wrote: “My father loved Dick Randall. I thought he was a neat man, myself. But just as Dick Randall didn’t cause the Crash of ’29, which set off a downward slide of the dude business, neither can Chan Libbey be blamed for World War II and the travel restrictions that finished it off.”

In the end, a grand vision turned into a crumbling reality, similar to many dude ranches across America. And yet, the OTO lives on at Cedar Creek. With preservation efforts still underway, only time will tell what’s in store for the site’s future. For now, you can still see where Molesworth’s chairs and tables stood. It’s a place that embodies the lifestyle embraced by many men and women, not just Chan T. Libbey. They longed to live as cowboys, wild and free.

Free to explore and discover, siblings Chandra and Channie Libbey were often the only kids at the OTO. | Courtesy of the Libbey Family

GROWING UP ON THE OTO

Days of Roy Rogers radio, secret caves, and pet coyotes

“OF COURSE, I WAS JUST a kid, but I always wanted to stay my whole life up there.” Such was the mindset of Chan “Channie” Libbey II, son of Chan T. Libbey, proprietor of the OTO Ranch from 1934 to ’49. As a boy, Channie’s OTO wasn’t much of a dude ranch. By then, it was a working ranch full of colorful cowboys, tall characters with a full-on desire to tease and torment the precocious, open-eyed Channie.

With his older sister, Chandra, as his fellow explorer, Channie found the OTO’s 3,500 acres to be a mystery in all directions. They had not a care in the world — Montana’s version of Huck Finn and Tom Sawyer — trying to find hidden caves, petrified wood, arrowheads, fishing creeks, and beaver pond swimming holes. Filling the wood box and finding coal were their only chores. Ice and ice cream were delights. Hot water was a gift.

“My sister and I quite often were the only kids up there,” Channie says. “We did a lot of stuff together.” Chandra adds: “Now let’s face it. You’re a little kid, and there are 186 horses… what’s not to love?”

In fact, the more you ask what childhood was like for these two octogenarians, who today live around Livingston and Paradise Valley, the more they exchange the vivid details of the ranch, one story at a time.

They owned a pet coyote named El Kiote, that someone had captured out of the den. “That thing bit me!” says Chandra, who admits she was “prey-sized” at that time. “The coyote used to sit on the porch of the Big House and steal the brown Pendleton OTO blankets off my baby brother’s buggy. And he’d howl when any cowboy would play the harmonica.”

“We always played in that Big House,” Channie says. “And there was this trap door in the ceiling down this one hall. Always wanted to get up there. And I don’t know how we managed it … maybe a ladder or something. We got up there, and there were 30 or 35 McClellan saddles.”

While their days were full of horseback adventures, their nights were busy listening to old radios and wind-up victrolas in the pool room. If the devices worked, the kids played Roy

Rogers episodes, Joe Louis fights, and such songs as “Keep Your Skirts Down, Mary Ann” and “Henrietta’s Wedding.”

It’s safe to say, it was a playground of dreams. Cargo planes landed. Trail drives came through. Old Yellowstone stagecoaches stopped by. Bears, moose, wolves, and rattlesnakes were dangers to avoid.

Each textured event etched big memories into the children’s minds.

“One room had a polar bear skin on the floor alongside a Navajo rug,” recalls Chandra. “You could sit on the bear’s neck, hold its ears, and ride to the moon. During World War II, the Air Force used the valley as a practice bombing run. The great planes swooped out from behind Castle Mountain, and we would dance with ecstasy.”

“When I walk up the hill and stand in that great emptiness, I know every rock and tree,” Chandra says. “I see my young self, rushing over the land on feet shod with joy.”

Channie’s best times rest closer to home. “Seeing my dad laughing with his friends or sitting on the porch carving a piece of wood. Those are the best memories.”

Such is life through the eyes of a child, when everyone else is too busy being a cowboy.

Jeff Moore is a writer and photographer from Livingston, Montana. He shoots and writes about outdoor subjects across the West, and returns inside to shoot food and product photography, including expensive guitars, duck decoys, and top-notch steaks; jeffmooreimages.net.

Jaye H. Wells

Posted at 18:54h, 03 JuneFrom a historic architecture perspective, sometimes circumstances such as the O.T.O.’s history gives us a gift. Since so very little of the original buildings were modified since 1939, we have a National Landmark in its near-original condition. After two years of Pop-Ups at the O.T.O. we can truly say a stay at the O.T.O. is as close to an early dude ranching experience as one can find these days. We hope it stays that way.

Laura Connelly

Posted at 10:56h, 06 JuneWhat a wonderful read. Thank you for a glimpse into dude ranch life and hardships beyond the owner’s control. Fascinating to be sure.