28 Sep The Illusion of Life

When people imagine a rustic log cabin in the Rocky Mountain West, they most likely envision a trophy deer mounted on the wall or above a fireplace. A memento from the surrounding wilderness, the animal’s antlers reach toward the ceiling, and its round, glassy eyes keep watch over the room. At any moment, it seems the spell it’s under might break, and the animal will thaw from its frozen position and spring to life.

In the Northern Rockies, the taxidermy mounts that adorn the walls of countless homes and businesses are as prized as any art collection. Selected by hunters and interior designers alike, they serve as decorative statements and mediums for storytelling. Taxidermy also symbolizes an undeniable aspect of culture in the Northern Rockies: Many of the people here seek a connection with the outdoors — even going so far as to give a sense of immortality to the creatures they’ve encountered, stalked, and hauled from the woods.

In the Northern Rockies, taxidermy is a common rustic design element for homes and businesses, chosen by interior designers and hunter homeowners as a decorative statement and a medium for storytelling.

And whether it’s documenting an epic hunt, an extinct species, or the curious oddity of a two-headed calf, this technical art inspires opinions. Some view it as grotesque and unnecessary, while others see it as the preservation of a spirited creature or treasured memory. Love it or hate it, taxidermy has a long history in the Rockies, and some would argue, it’s even emblematic of this region.

In Montana, taxidermy played a surprising and important role in bison conservation. William Temple Hornaday — the chief taxidermist at the United States National Museum (now the Smithsonian Institute) from 1882 to 1890 — was shocked and outraged when he discovered that the large herds of bison he’d witnessed out West were vanishing. While their population was once in the tens of millions, by the late 1880s fewer than 1,000 bison remained, and, according to the National Park Service, there were only about two dozen left in Yellowstone, wintering in Pelican Valley.

In a home’s entryway, a taxidermied buck welcomes guests.

“The wild buffalo is practically gone forever, and in a few more years, when the whitened bones of the last bleaching skeleton shall have been picked up and shipped East for commercial uses, nothing will remain of him save his old, well-worn trails along the water-courses, a few museum specimens, and regret for his fate,” wrote Hornaday in his 1889 book The Extermination of the American Bison. In order to call attention to the bison’s decline, educate the public about their magnificence, and generate interest in protecting them, Hornaday knew their size and impact needed to be experienced; he had to instill awe.

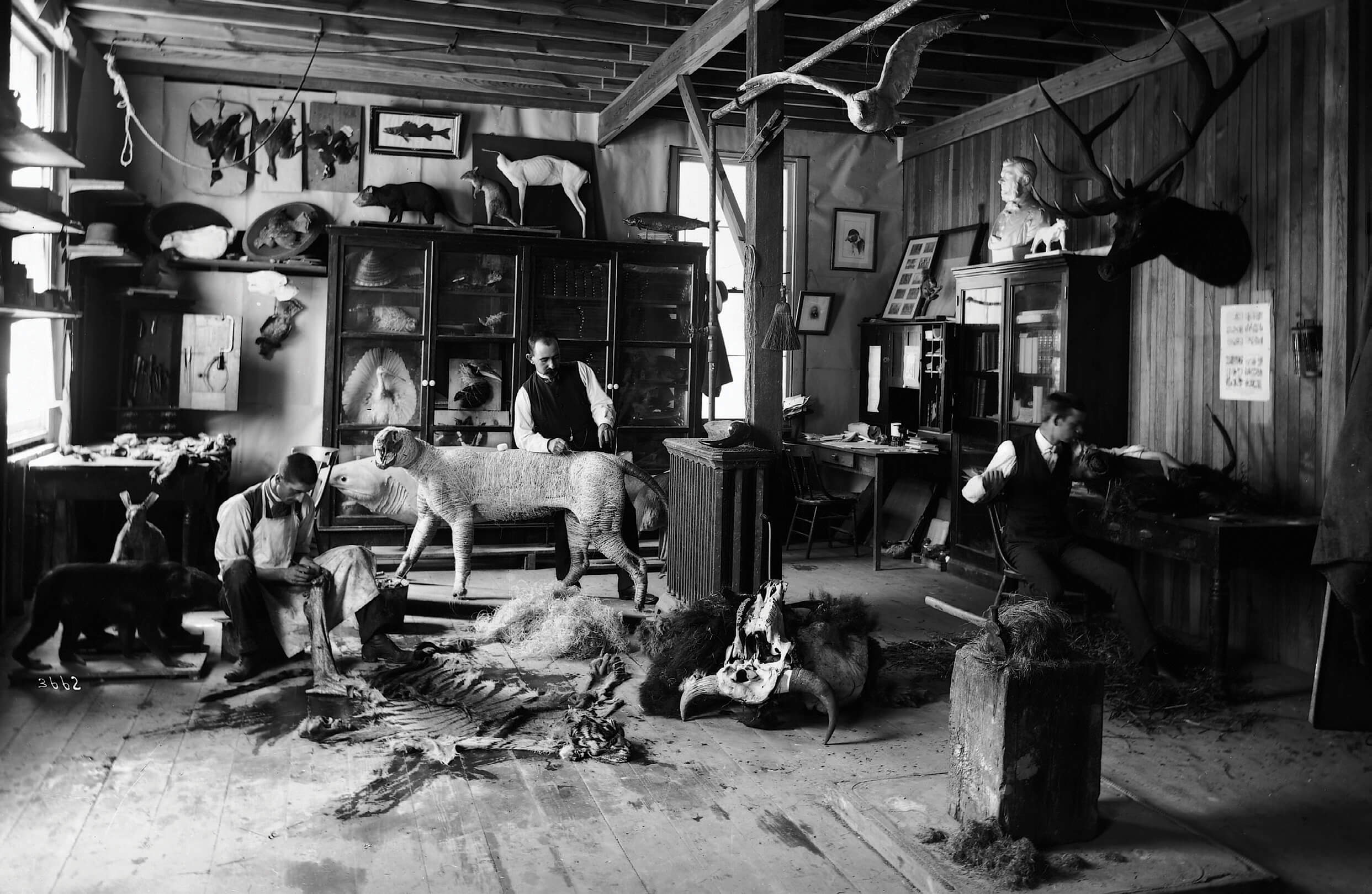

In 1886, he organized an expedition, leading a team into Montana Territory to gather samples of the quickly disappearing species before it was gone forever. Hornaday’s goal was to preserve examples of the wooly mammals for the United States National Museum collections, allowing future generations to know what they looked like after they were extinct. He and his team returned with 44 specimens and worked with a taxidermy team to produce an exhibition, displaying six of these large beasts in life-like positions as part of a diorama that included grass and dirt from their home turf of Montana. The popular exhibit, which opened in 1887, drew crowds and was displayed at the Smithsonian Institute for 70 years. Today, the original taxidermied display resides in the Museum of the Northern Great Plains in Fort Benton, Montana.

With a collection of about 1,000 species, the Draper Natural History Museum at the Buffalo Bill Center of the West in Cody, Wyoming, uses the taxidermic mounts for educational purposes, providing a closer look at the animals that live within the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem.

In addition to the diorama, Hornaday arranged for a small herd of bison to be sent to Washington, D.C., where they grazed in the South Yard behind the Smithsonian Castle. According to the institute, “The live animals proved even more popular, leading to the founding of the National Zoological Park as part of the Smithsonian in 1888, with Hornaday as its first director.”

Hornaday’s expedition catalyzed the movement to save the bison, and he dedicated most of his life to the animal’s recovery. He became a leader in the effort with his book, and in 1905, he founded the American Bison Society with Theodore Roosevelt and other pioneering conservationists.

Taxidermist Ray Hatfield moved to Cody, Wyoming, in 2000 after he was commissioned by the Draper Natural History Museum to help create their exhibits.

According to the Museum of Idaho in downtown Idaho Falls, taxidermy dates back to the ancient Egyptians, who developed forms of animal preservation as early as 2200 B.C. These life-like creatures, often the pets of pharaohs, were buried in tombs alongside their owners.

In Europe, an interest in taxidermy developed during the 16th century with the discovery of new animal species. With the absence of photography, it was a tool that allowed scientists and naturalists to study animals they never would have encountered in the wild. Charles Darwin, for example, learned the skill at age 17, and he used it in the 1830s to preserve the Galapagos finch, which had a distinctly different beak shape from finches found in other locales. These specimens helped support his theory of evolution through natural selection.

Today, he and his team of 13 preserve an estimated 2,000 animals a year for public and private clients.

The oldest preserved critter known today is a 500-year-old crocodile that hangs from the ceiling of a cathedral in Ponte Nossa, Italy. It’s an impressive feat considering the initial methods were rudimentary; early specimens were stuffed with rags and sawdust, sometimes disfiguring the animals. For instance, a poorly preserved specimen of the extinct dodo bird — a composite creature made from plaster and swan and goose feathers in the 1890s — led to misconceptions about the species’ appearance.

During these early attempts, a key component of preserving animals was keeping bugs away. According to the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History, French ornithologist Jean-Baptiste Bécœur was the first to develop a method for deterring insects when he created an arsenical soap around 1743. Though he intended to keep his concoction secret, other taxidermists reverse-engineered the formula after his death. By the mid-19th century, this arsenic-based soap was the standard for museums and collectors, and it led to a golden age of taxidermy that continued until the early 1900s.

The museum-quality taxidermy that Hatfield produces, is technical, requiring details and expressions that capture the animals’ essence.

Beyond scientific purposes, some historic taxidermy specimens wound up in “cabinets of curiosities,” which were used by wealthy collectors to display notable objects from far-reaching corners of the world, including rare animals and beloved pets. Many of these private collections were later donated to institutions, leading to the establishment of the modern natural history museum.

Today, museums use taxidermy — along with skins and skeletons — to help establish the taxonomies of species, take DNA samples, and preserve remnants of extinct animals. The Draper Natural History Museum at the Buffalo Bill Center of the West in Cody, Wyoming, has accumulated approximately 1,000 species with roughly 600 birds and 400 mammals that are preserved in different forms, with the oldest dating back to 1870. “The collection represents both an important documentation of change in the process of taxidermy, as well as some of the early initial roles of taxidermy,” says Nathan Doerr, Willis McDonald IV Curator of Natural Science at the Draper Natural History Museum. In the museum’s collection, more recent taxidermy specimens can include samples of insecticides, heavy metals, and other chemicals found in our environment today.

“Those of us out West see taxidermy on a regular basis: in living rooms, offices, or in bars and restaurants. But for those outside the West, their first encounters with taxidermy are in natural history museum halls or dioramas that represent life on Earth or a specific ecosystem,” Doerr says, adding that, for its exhibits, the center relies on salvaged specimens from state and federal agencies and donations from a bird rescue organization. “We rely on taxidermy in exhibitions to tell the story of this amazing place we call the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem, and to give a really up-close look at these animals.”

Hatfield and his team work out of a large warehouse in Cody. Along with creating mounts, he also designs and builds the animals’ elaborate habitats for some clients.

Museum-quality taxidermy is technical, requiring extensive knowledge about an animal’s subtleties. “Knowing how to snarl a lip or sculpt tension into the body of a stalking lion, or choosing which size and color of glass eyeball to use, is crucial to the specimen’s overall success,” writes Rachel Poliquin, author of the 2015 New York Times article The Breathless Zoo: Taxidermy and the Cultures of Longing.“ People often ask me how to tell bad taxidermy from good. The answer is simple: If the creature looks like a dead thing sewn together, it’s bad. But if, even for the briefest second, it could be mistaken for a living creature, it’s good.”

In Cody, Wyoming, Ray Hatfield was commissioned in 2000 to create hundreds of taxidermied animals for displays at the Draper Museum. His interest in taxidermy started in the eighth grade with preserving butterflies. Then in a junior high art show, he displayed a large fish he’d caught and taxidermied, and “people started calling.”

In his large warehouse, Hatfield and his team of 13 preserve some 2,000 animals a year — from the tiniest of mice to the mightiest of lions — for clients that range from world-class museums to trophy hunters. For some, they also design and build the animals’ extensive habitats, mirroring the surroundings from which they came.

An elk mount, Hatfield says, takes six months from start to finish. And he explains that for any successful mount, careful attention to detail in the face and expression is key, down to mimicking the dew drops on an animal’s whiskers on a cold morning. “I like to try and bring the animals back to life as much as possible so that they can be enjoyed for, hopefully, generations,” Hatfield adds. “That’s the most rewarding part, is that those stories live on.”

No Comments