23 Jul Artist of the West: Television West

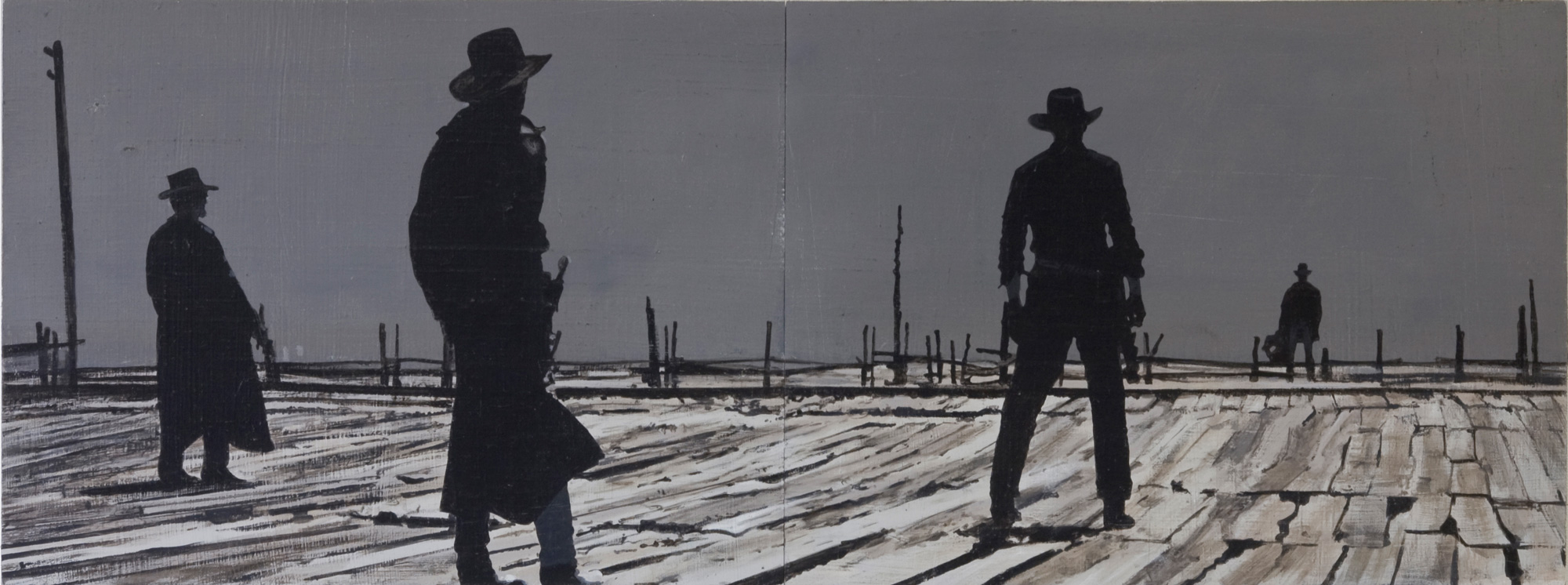

DELICIOUSLY STEEPED IN THE CINEMATIC, painter Gordon McConnell, is drawn to stop action movement, the blustery stillness of an instant, with a director-like passion to capture and free at the same time.

Using iconic scenes from old Westerns, McConnell reaches into our collective memory and procures elements — teams of horses, riders across the plains, riflemen in the saddle — tinged with a bittersweet longing.

These are the paintings that spring from the mind and hand of a thoughtful, curatorial artist like McConnell, colored by his childhood afternoons sitting in front of an old black and white television watching serial Western dramas with the flickering reception one gets in a small Colorado town.

“I’ve always been deeply stirred by the Western folklore, by its people, past and present,” he says, standing before a small 18-by-24-inch masonite surface, in his Billings, Mont., studio. “And here I wanted an image of riders, riding parallel to the picture frame, filmed from a tracking-shot, which is taken from a camera truck.”

Like the ancient Camera Obscura method for sketching (circa 956-1038 AD), McConnell substitutes the old pinhole version for a modern day slide projector, throwing the outline of a slide shot up on the canvas in front of him.

With every layer of paint, using limitless shades of gray, he brings with it decades, no centuries, of art history pureed through his own churning creative process. By using the Camera Obscura he harkens back on historical methodology. His work also references Gerhard Richter, who re-envisioned portraiture through “photographic” painting. Besides the obvious choice of subject matter, which builds upon the Western as a vital self-imagery of Americans and heroism.

Picking up a knife-load of black acrylic he presses the paint to the surface. Then, using a squeegee he spreads the color across, leaving behind hints of the painting underneath. This is a technique McConnell uses quite often to give his paintings a sense of something old, used. A kind of indelible mark of time. It is not only the degenerated image, the time-worn feeling of the film, but it is also the erosion of the image each time we think about it, as if our minds could wear out a thought.

McConnell uses a fine brush to bring out the details of a horse blazing the plains, a scene from a late 1930s movie with Glenn Ford and William Holden. There is something intimate about the silhouette, the way we know people we see in films and on television, the one-way relationship of fame. It’s haunting and addicting.

“We have so many experiences that aren’t ‘real’ through the cinema,” McConnell says. “How do we access that? And how does that compare to our life in the West? I want to hold onto an aspect of the movies and part of what appeals to me is the illusion.”

At first he works like a photorealist, comparing the image on the projector to the image he’s creating.

“I get what information I need from that,” he says, taking a very small hit of white on his brush and applying it to the edge of the horse in the painting. “My experience is like watching the movie for the first time. I’m the viewer and the performer. I’m interpreting, blurring the photo image into shapes made with a brush to try to recreate a fragment of a film. A film has 100,000 frames, and this is just one.”

Working with an extremely limited palette, mostly black, white and grays, with subtle tones of sometimes blue and sometimes brown blended in, McConnell communicates a fragility to his art, a reference to an era gone and yet never gone, an abstraction of time, an ambiguity of reference.

“Westerns are simple stories,” he says. “The black and white element is all we need to make that connection to the narrative.”

And so it is with his work.

John Hull, a narrative painter and head of the art department at the College of Charleston, S.C., has known McConnell for more than 20 years.

“Gordon McConnell is looking at the West in a different way than Remington for example who had access to the West but was not a man of the West,” Hull says. “The nostalgia in McConnell’s work is that even though he’s a man of the West it’s not for a West that actually existed.”

Hull sees McConnell’s canvas size, reflecting the size of a television screen, growing from the mythic landscape of the Television West.

“The way he uses a limited palette, strikes me that this is about looking at the West through the eyes of a boy and a TV set,” Hull says. “A lot of the ways McConnell invents to use paint, the different viscosities, are ways he has of representing the blur, the flickering black and white screen connected to an antenna. I’ve seen him make other kinds of paintings but ultimately there is the dream he has of the West that is consistent and is represented by the memory, not necessarily by what happened, but things that occurred in his mind as a young man.”

Of interest to Hull is McConnell’s attachment to memory, the things people use to build their lives upon.

“I think there’s a uniqueness to McConnell’s work, in his willingness to believe so completely in the images he uses,” he says. “A lot of Western painters will make a nod to Remington or Russell but they’re essentially using the same tools to represent a contemporary view of the West. While McConnell could do that, he has access to the western landscape, his focus is always deeply rooted in the imagery of the Western film. He’s not trying to move away from that at all.”

Hull owns a few of McConnell’s paintings.

“I’ve lived with his paintings for a long time and continue to be refreshed by them,” he says. “There is one in particular that I look at every day and I am renewed.”

Another aspect of McConnell’s work is the intensely personal, intimate relationship we have with movies — sitting in a dark theater, fully enveloped in an alternate reality, cushioned and comforted in safety as our heroes play across the screen in danger, in love — and how those experiences shaped the way we view right and wrong.

“I remember when I first saw John Ford’s Stagecoach (1939) in the mid-70s,” McConnell says. “The print was battered, the images de-resolved, flickering and stuttering. Details of the coach, horses and characters dissolved in abstract shadows as the searing glare of the Arizona desert spilled into the auditorium. Still, the compelling story and performances, dynamic action set-pieces, and powerful cinematic compositions came through. In its ruined state the old film seemed like a relic of an actual frontier.”

Katherine Erickson, of EVOKE Contemporary, in Santa Fe, N.M., is one of the galleries that represents McConnell’s work.

“As the director of a non-traditional gallery, I like Gordon’s contemporary take on the Western subject,” she says. “I find that his work appeals to all collectors, young and old. He has found a way of presenting nostalgia of the West with a fresh style and format. His paintings can be displayed in a very modern minimalistic environment or a more traditional western scenario with cowboy collectibles and artifacts. I particularly love the way he captures the action of the old Western films, and that he chooses to paint in a monochromatic scheme — it’s a perpetual play of the old and the new.”

According to Erickson, McConnell’s work has resonated with many of her clients.

“His work has been received in Santa Fe almost as if he invented the West,” she says. “Collectors were just so hungry for a new perspective on a great old era of American history. This is an exciting tribute to the life many of us do not want to see disappear.”

Like cultural road signs, familiar, readable and so startlingly new, each visit to a McConnell painting brings us face to face with another revelation of who we are, as a society and what has combined to this point to get us here.

- ANTHOLOGY – RUNNING FIGHT | acrylic on canvas | 30″ X 40″

- ROLLING | acrylic on canvas | 33″ X 40″

- PAST VANISHING | acrylic on canvas | 33″ X 40″

- “Showdown – Three to One” | Acrylic on Two Hardboard Panels | 24 x 48 inches

No Comments