01 Feb Sunset on the Greys

We’re a couple dozen miles down a rolling, dusty, backcountry road that shadows the Greys River in western Wyoming, and I can’t find the dream pool I want to fish. This uncertainty has my 15-year-old daughter stressed out.

“Dad? Are we lost?” she asks for the third or fourth time.

“No,” I tell her, “not yet.”

It’s day two of what’s become our annual three-day father-daughter fishing trip, and I’m hoping to find a bit of redemption through fine- spotted Snake River cutthroat. We’d heard about this “secret” spot from a kindly local grandfather a day earlier. As I scan the river below and to my right, his descriptive roadmap is flapping around in my head.

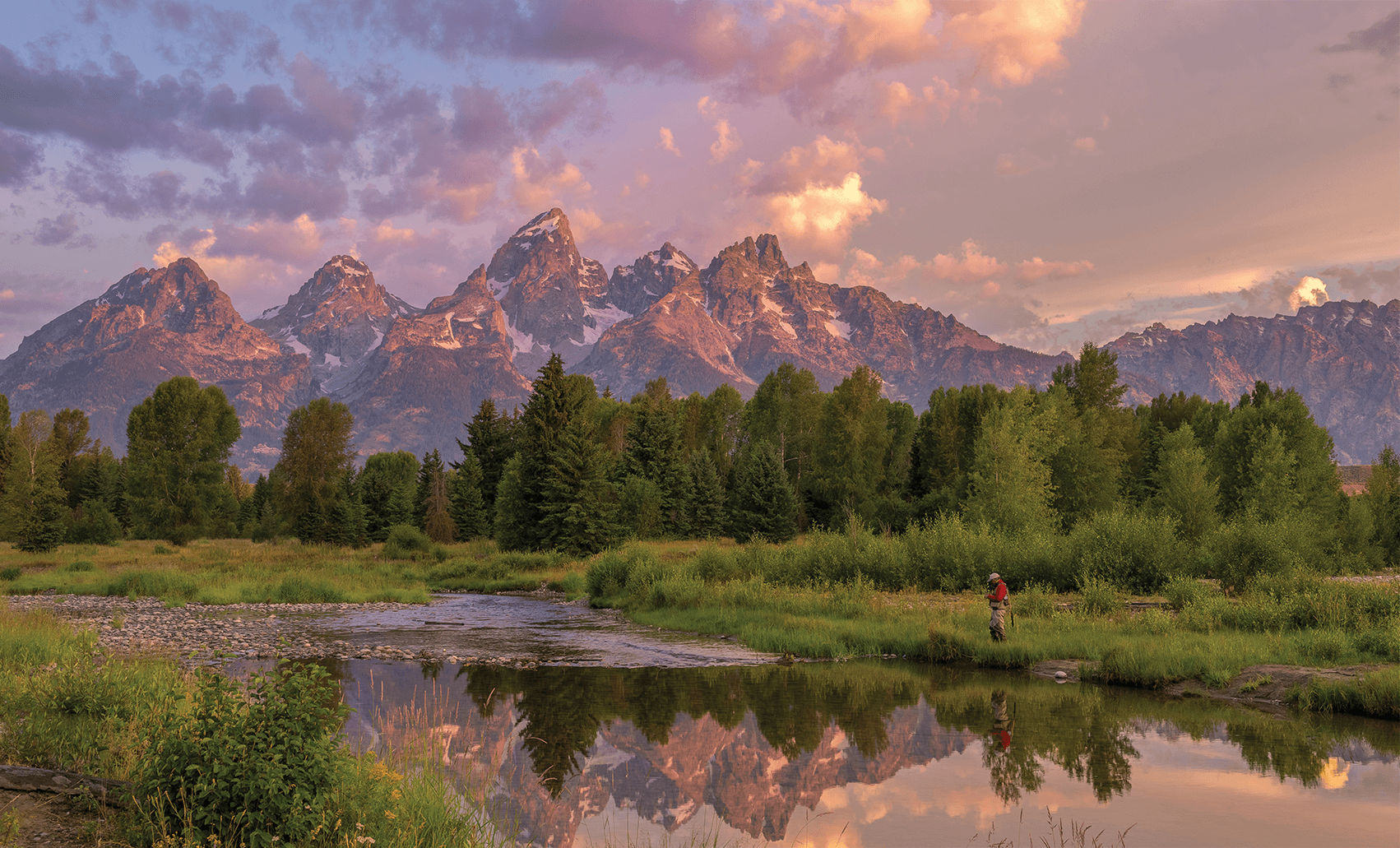

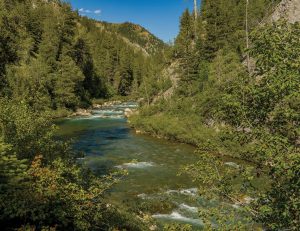

The Greys River, near Alpine, Wyoming, offers plentiful opportunities to wet a line in the most picturesque of Western settings.

“It’s by a big landslide. It’s a little hard to get to, but the fish stack up,” he said as we wriggled free of our waders after fishing the Snake near the town of Alpine. “Set your odometer. You can’t miss it.”

Odometer set, we started late that bright chilly autumn morning. Beyond town and off pavement, the gravel road curved past blazing aspen groves, golden veins splintering the dark pine forests of the Wyoming Range like frozen lightning. Scattered herds of elk hunters had taken root along the road; their canvas tents, trailers, and trucks encircled like modern-day homesteaders, stovepipe smoke writhing into the cobalt blue sky.

We could use a “can’t-miss” after yesterday. On a sunny Friday morning, I’d stumbled on an unusually empty stretch of water in the Snake River Canyon. Having gone a year without casting a fly rod, my daughter looked stiff and off-rhythm, her shoulders slumping. A gusty breeze bullied her casts, piling up her fly line in the parking lot by the boat ramp. After a few minutes of practice, she started to perk up. We were ready for the river.

The river was not ready for us, though. Slow fishing and increasing wind frustrated her efforts, sapping her interest. Then, the trout began to move. A beguiling blue-winged olive hatch had started. I hastily took over casting for both of us. Ignoring most of my drifts, the cutthroats sipped the dainty mayflies.

Then, from deep in the run, a silver streak pounced and immediately tried to shake the fly loose. Having dropped my net a few yards away, I turned to my daughter as I stripped in line.

“Grab the net!” I shouted with some urgency.

“Where is it?” she responded in a shrill voice, reflecting my energy.

The author holds the finest fine-spotted Snake River cutthroat of the trip, a trout coaxed from the Greys River on a clear autumn day. Photo by Andrew Becker

“It’s over there. Quick! Let’s land this one.”

She fluttered around before finding the net, then gingerly picked her way over cobblestones and around boulders to deliver it. Reaching for the wood handle, I yanked too hard on the rod, and — snap — the tippet broke, the hefty fish gone.

“I’m sorry. I’m sorry,” she said, disappointment already pooling around her.

“It’s fine, honey,” I said with little disguise to my voice as I sat down on a rock to collect myself.

Upstream, the river widened into a long shallow pool where rising trout dimpled the water’s soft surface. Another angler glanced over his shoulder at us, fish fighting on the reel. He volunteered what they were eating and, in a selfless gesture, surrendered his pool of success.

The fishing came fast. The cutthroats slurped up mayflies as they bounced on the surface. My daughter snapped smiley selfies with me in the background, rod bent, focused. She showed little interest in fishing except when I offered her a peek at the stunningly bejeweled camouflage and telling red-orange slash in the net.

Jolting me out of my reverie, she called to me from downstream, despondent and forlorn on this glorious school-free day, adrift in the magnificent mountain setting. Her message was clear: I was too far away; the water was too deep to wade. I hesitated for a moment, then turned to her.

As the sun dropped behind wooded peaks, a single aspen spotlighted by the slanting sun, we retreated to the parking lot, where we met the generous angler-grandfather. He told us his story, shared his honey hole on the Greys, and gave me a foamy purple beetle fly to try out.

“It’s nice to see a father and daughter fishing together,” he said, the blood rising in my face as I thought about my reaction to the lost fish and who was doing all the casting.

The tell-tale tail of the fine-spotted Snake River cutthroat is most notable for its gathering spots.

Good parenting, like fishing well, demands concentration, mindfulness, and regular recalibration. It requires staying true to bedrock fundamentals while being open to various tactics. Finding the right depth. Being present.

And as Ike — the grumpy old fishing guide in the 2023 film Mending the Line — tells John — the grieving war veteran who turns to him for therapy — the most important part of fly fishing is humility: “It ain’t easy. It takes practice. Not like playing with your goddamn phone.”

The first-generation iPhone was exactly three months old when I found myself unexpectedly floating above the moment my daughter and her twin brother arrived, 10 weeks premature. She had come out flopping and twisting, measuring 13 inches and weighing just over 2 pounds — decent for trout, but startlingly delicate for a newborn. At a week old, I could slide my wedding band over her balled fist and up to her armpit.

She grew into a dancing whirlwind of magnetic force, with more energy than her tiny frame could handle. We called her our “Summer Squall,” which was fitting when she acted as if the torrent of harsh words, gale-force screams, and downpour of tears had never happened.

Progressing through elementary school, these storms became spells and even seasons, turning longer and sometimes darker. Some of her sweetness went sour. Mole hills rose into mountains.

Middle school — math and mean girls, in particular — pierced her soul. While others her age sprouted, she was sometimes mistaken for students two, even three, years younger.

And then, the pandemic.

Like many teenage girls, my daughter already felt out of sync before COVID. Add war, social unrest, and the relentless pressure of the fantasy world of social media to the angsty transition from childhood to adulthood, and you have what researchers are calling a mental health crisis for teens, and an epidemic for girls.

In 2021, the year before my daughter’s freshman year, 57 percent of American high school girls said they had persistent feelings of sadness or hopelessness. Where we live in the Mountain West, death by suicide rates routinely outpace the rest of the country. In 2021, three out of 10 American girls seriously considered attempting suicide, a rate nearly 60 percent higher than a decade earlier, according to a survey by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

High school hadn’t even started, and she was worn down. My wife took worried phone calls from a sleepaway camp about our daughter’s mental health. The transition to a new school had been a barrage. Then, two weeks into the school year, a former classmate took his own life. My girl was frazzled, second-guessing herself, desperate not to disappoint.

Fishing wasn’t the answer she’d hoped to hear, but it had worked for me as I walked smack into middle age. Like an exploding number of others, I had anchored to fly fishing at the start of COVID. I dug in deeper after leaving a stressful job months into the pandemic.

Aching to have something we could share, a skill to best the boys, a way to get lost in something without feeling lost, I’d bought her waders and boots. In handing her the fly rod that had quickly bored her other brother, I bestowed upon her all the inherent and subtle lessons, a-ha moments, and lifetime’s worth of metaphors that fly fishing provides. I’d done my job.

“But I’m no good at this, Dad! I’m not good at anything!” was her reply.

“Just keep trying; it takes time. You’ll get it.”

Fine-spotted Snake River cutthroat trout range between Jackson Lake, in Grand Teton National Park, and Palisades Reservoir, on the border of Idaho and Wyoming. The species is genetically indistinguishable from the famed Yellowstone trout, from which they derive.

The odometer mocks me. I’ve driven past an airstrip, a gated community, and unflappable cows; stopped twice to go to the bathroom; and missed the landslide. Still, the day has warmed, and while the river is low, it’s also clear. I pull into a grassy campsite a few feet from what looks like fishy water.

But there’s not even a fish to spook. I’m feeling a bit anxious as I head downstream to the next alluring bend. Nothing. I try a riffle. Nope. Then a tailout. Boulder pockets. Underneath the shady overhanging tree branches around the corner. The seams and foam and everything else. Zilch.

And then, I hear screaming.

I climb up the bank to the road and walk to where I left her. With red-rimmed eyes, she demands to know where I went, why I left her. She hates fishing: “Don’t you get it, Dad?”

I yell back about courage and bravery and being able to handle herself. Besides, I’m just trying to find us some fish.

It’s time for lunch.

Over sandwiches, we talk about life in high school; about confidence and believing in ourselves — in taking risks and trying new challenges; how excellent it is to be a beginner. It’s a great speech to give to a 50-year-old man thinking of changing careers. She agrees to give it another go; says she just wants to be with me. And it hits me, like a rock to my dumb head.

Four hours after our arrival, we are back on the water. This time, we try a run along a far cutbank when something catches my eye. Dangling from the limbs of an otherwise naked willow hang two weather-beaten and crusty grasshopper patterns strung up like forgotten Christmas ornaments. A foamy, fuzzy gift; a hint of the past.

After retrieving the booty, I tie on a Franken-fly, a small tawny hopper imitation that has no business being here this time of year. Below that, a Prince Nymph. I false cast twice to get my line out and present. Repeat. Again. Finally, the fly dips under the surface, and I lift the rod. A small cutthroat wiggles before quickly rolling over and into the net. I release the fish and rinse my hand in the water, the stink of skunk off us. With the sun slipping behind us, we share a happy selfie. Her turn.

“Can you help me?” she asks.

I want to say, “No.” I want her to do it. But that’s not the answer right now.

She nestles in front of me, and we cast the hopper-dropper to the bank, under the willows. Ten minutes go by as we sidestep upstream inch-by-inch. Then, a rise and a hookset. I’m stripping the line from above her head, the rod bending to a much stronger fish than the one I just released. Reeling in quickly, I hand her the rod. She and the fish are both shaking.

“Oh, Dad. Oh, Dad.”

The author’s daughter relishes a brown trout caught on a dry fly along the Green River in Utah. Photo by Andrew Becker

“Keep going, Lucy! You got it.”

I slip the net’s rubber basket into the water and come up with the finest fine-spotted Snake River cutthroat of the trip. My daughter is beaming.

“We did it!” she cries.

Maybe fishing is the answer. It just depends on the question.

An artist’s rendition of the author and his daughter rigging up fly rods ahead of a day on the river. Painted by the author’s mother, Barbara Becker.

Driving south the next day, we find it: The beyond-my-wildest-dreams pool, in a place I don’t expect. It holds 40, maybe 50 meaty cutthroat — I can’t count them all — stacked up, tails lazily fanning in unison, averaging at least 18 inches. Still, they pay me and my fly no mind. Another time.

Back home, I bask in the afterglow of our trip: the color of the leaves, the hungry fish, our time together, the sunset on the Greys.

But something else has consumed our daughter: A friend took her own life two days after our return. One night I’m laying in bed about to turn off the lights when she comes in to say goodnight. She’s been crying. She asks an innocently horrible question that makes me sit up.

“Is it OK to still grieve?”

“Of course,” I say. “It’s always OK to grieve. No one can say when or how to stop.”

“The last time I spoke to her was two days before she died. We texted. The last thing I said to her was, ‘I love you.’”

I stumble for the right words, trying to help her describe how she feels.

“I don’t know when you’ll get over it. But it takes time. Just keep trying.”

Andrew Becker has been a journalist, writer, and producer for more than 25 years. His reporting and writing has appeared on National Public Radio and PBS/Frontline, as well as in the Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, New York Times, Reveal, Outside, Climbing, High Country News, and Tahoe Quarterly, among others. He lives in Salt Lake City, where he fishes as much as his family will tolerate.

Ken Takata is a commercial and fine-art photographer specializing in fly fishing, landscape, and architectural imagery. Takata currently resides in northwest Wyoming and has lived in the Rocky Mountain West for the past 40 years.

No Comments