24 Nov Pride of a Horse Nation

The Apsáalooke (Crow) Nation has long been renowned for its spectacular beadwork and horsemanship. On June 25, 1805, two Canadian fur traders, François-Antoine Larocque and Charles McKenzie, witnessed the equestrian parade of more than 2,000 Crow people, including some 645 warriors, who filed through Hidatsa and Mandan villages near the confluence of the Knife and Missouri rivers in North Dakota. The fur traders wrote about the experience and their accounts were later published in Early Fur Trade on the Northern Plains: Canadian Traders Among the Mandan and Hidatsa Indians, 1738-1818. McKenzie states that the “Rocky Mountain Indians [presented] the handsomest sight that one could imagine — all on horseback. [They] had the appearance of an army [and] I could believe they were the best riders in the world.”

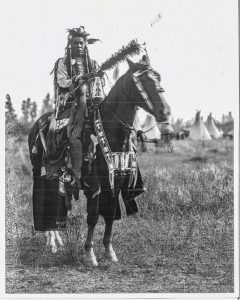

This portrait by Richard Throssel, ca. 1905-11, is one of only a handful that depict men mounted on horses decked out in the type of equestrian gear produced and used exclusively by Crow women. The massive, heavily-beaded collar is typical of the object type that Apsáalooke women regarded as the one truly essential ornament for a parade horse. AMERICAN HERITAGE CENTER, UNIVERSITY OF WYOMING, PHOTO NO. TP194

Throughout the subsequent pre-reservation period, Euro-American observers consistently praised Crow horsemanship and their talent as artists, most notably their distinctive style of beadwork, which functioned as an expression of tribal identity. As Della Big Hair, a contemporary Crow beadworker in Montana, said during an interview with Ramona Medicine Crow as a part of John Molloy Gallery’s 2006 exhibition Apsáalooke: Art and Tradition, “This art represents who we are and where we come from. If you look at other tribes’ beadwork, our Crow style stands out.”

Aside from fragmentary references, the surviving record of early Crow equestrian parades is, unfortunately, limited by a dearth of pictorial evidence and examples of Apsáalooke horse gear that predate 1860. Larocque documented that women’s saddles in 1805 featured high pommels and cantles, which later became a hallmark trait. He makes no reference, however, to their artistic treatment. In 1832, artist George Catlin depicted the trappings of He Who Jumps Over All’s horse, including a “most extravagant and magnificent crupper, embossed and fringed with rows of beautiful shells and porcupine quills of various colours.” In 1837, the artist Alfred Jacob Miller observed that women’s saddles were decorated with “pendants made of brilliant colors, worked tastefully with beads and fringes.”

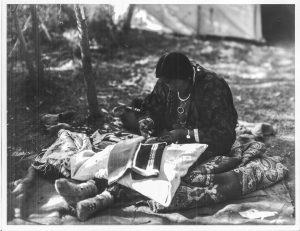

Photographed by Throssel while embroidering a Crow-style man’s panel legging, this Apsáalooke woman, “Kills Good” or Clara White Hip, was Mardell Hogan Plainfeather’s maternal aunt. Plainfeather said, “Her beadwork was among the best in the tribe, according to my mother, and she recalls that she named some of her grandchildren for her talent.” AMERICAN HERITAGE CENTER, UNIVERSITY OF WYOMING, PHOTO NO. TP700

Well-provenienced collections of early Crow horse tack are virtually nonexistent. A small group of cruppers, the earliest of which was accessioned by the Ethnological Museum of Berlin in 1846, is generally attributed by art historians as “Crow/Hidatsa.” Stylistic similarities and virtually identical modes of construction suggest that these pony-beaded cruppers were the direct precursor of later-day examples. In 1856, Denig corroborated the Apsáalooke’s use of “highly ornamented saddles and bridles of their own making, scarlet collars and housings (i.e., saddle blankets),” but his comments are not sufficiently detailed to determine how closely these objects resembled their late 19th-century counterparts. A stirrup with a sparsely beaded pendant, accessioned by the National Museum of Natural History in 1868, may constitute the earliest documented piece of Crow equestrian gear.

Based on historic photographs, particularly those taken by Fred Miller and Richard Throssel between 1898 and 1910, a complete assemblage of Apsáalooke equestrian gear included a horse collar, saddle (with beaded pommel, cantle, and stirrup flaps), saddle blanket, crupper, and bridle. Crow cradles and lance cases were noteworthy accessories to these trappings. Although men were occasionally photographed on horses decked out in this fashion, these objects were used exclusively by Apsáalooke women, and equestrian parades ultimately were, and still are, a visual tribute to their artistry.

The declarative features of Apsáalooke parade bridles include compositional and textural contrasts. Lane-stitch borders on the headstall accentuate unbeaded panels that were subtly decorated with a light coat of red pigment, thus providing an unobtrusive backdrop from which the large, fully-beaded keyhole ornament was suspended. NATIONAL MUSEUM OF THE AMERICAN INDIAN, SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION, CATALOG NUMBER 12/6404

Given its size and brilliant color composition, the horse collar has long been the indispensable accouterment for a parade horse. Indeed, William Wildschut, a collector and then-resident of Billings, Montana, observed in the 1920s that “no Crow woman would consider her riding horse fit to take part in a parade unless it wore one of these beaded collars.” Their aesthetic appeal is primarily attributable to the striking contrast between the collar’s large, solidly beaded, rectangular panel and motifs embroidered on the straps that secured it to the horse’s neck. Tall isosceles triangles, bordered by inserts of red cloth, dominate design schemes on collar straps.

By the first decade of the 20th century, canvas was the foundational material for saddle blankets. Decorative strips that bordered their lower rear margins comprised the principal ornamentation. Beadwork was applied directly to rectangular sections of cloth, alternately red and dark blue. When a horse was saddled and the rider mounted, this strip and the solidly beaded tabs at its corners were the only visible portions of the blanket.

The two halves of a Crow crupper, like those of their pony-beaded predecessors, consist of rawhide or commercial leather front sections and buckskin rear panels, which are connected by a strap of leather that passes under the horse’s tail. Embroidery on reservation-period cruppers superbly illustrates the palette traditionally associated with Crow beaded art, which emphasized light blue and pink as backgrounds and employed white sparingly, most commonly as an outline. A cloth-covered rawhide pendant, resembling a clock pendulum, was attached to each half of a crupper. Forged metal spoons dangled from this ornament, and their jingling produced an almost musical accompaniment to the rhythm of a horse’s hooves.

Bridles used for parades typically featured a large, solidly beaded, keyhole-shaped ornament, one bordered by dyed tufts of thread-wrapped horsehair, which was suspended from the sparsely decorated headstall’s browband and covered much of the horse’s face. This ensemble was completed by a Spanish bit, which appears in historical photographs as a series of finely meshed chains attached to metal shanks dangling beneath the horse’s lower jaw.

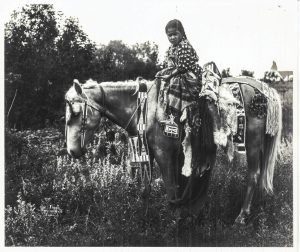

The elk-tooth dress, pictured here in a photograph by Throssel, was and arguably still is the centerpiece of Apsáalooke female regalia. Apsáalooke artist Gladys Jefferson states that such dresses were used originally to “outfit your daughter-in-law or your sister-in-law. It was basically a wedding dress.” According to Plainfeather, “If a wife and all her female children were attired in these dresses, it was a sign of a family of means, one with a good provider.” AMERICAN HERITAGE CENTER, UNIVERSITY OF WYOMING, PHOTO NO. TP215

Given their prevalence in photographs from the turn of the 20th century, and the continued use of heirloom bits in contemporary parades at Crow Fair, archeologists James Keyser and Mark Mitchell conclude that “[n]o other trade item has retained such importance for so long in the same form” as the Spanish chain bit. Indeed, journal entries by Larocque and McKenzie indicate that, by 1805, Spanish bits were already in limited circulation among the Upper Missouri tribes. In motion, the jingling of a chain bit imparted a sense of kinetic energy and proclaimed the approach of a parade horse.

Connoisseurs of Apsáalooke art have long admired the sheer beauty of Crow equestrian gear. However, previous analysts rarely attempted to quantify the labor invested in its creation. During a 1999 exhibit in the Alcoa Foundation Hall of American Indians at the Carnegie Museum of Natural History in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, there was a horse mannequin decked out with trappings commonly displayed in reservation-period parades. A tape-recorded message, which the visitor could activate, stated that the total number of beads embroidered on these artifacts was 228,925. The horse collar alone contained 43,086 beads, and the combined weight of this assemblage of horse gear was 33 pounds, 11 ounces. According to the exhibit text, seed beads in 1900 were sold in hanks (10 to 12 strands) for 15 to 20 cents per hank. At that time, the number of beads needed for a complete horse outfit would have cost about $10.25.

These figures should be regarded as painstakingly meticulous estimates, ones generated by Melissa Elsberry, a curatorial assistant who multiplied the average number of beads per row by the number of rows per inch, and then, square inches covered by beadwork. The exhibit provided no estimate of the time spent crafting this regalia. However, James “Putt” Thompson, owner of the Custer Battlefield Trading Post, obtained estimates from Crow and Cheyenne beadworkers for production times associated with less ambitious projects for an exhibition on Plains Indian art at the University of Tennessee in 1995.

In He Who Jumps Over All, George Catlin’s depiction of a warrior’s regalia and the equestrian gear displayed on his horse is consistent with the description provided in the artist’s journal. Catlin observed He Who Jumps Over All at a Hidatsa village, located near the mouth of the Knife River in North Dakota.

Most notably, Merle Jean Harris, a Crow woman, was then working on a striped wedding robe. She estimated that beading one 40-inch-long stripe with cotton thread would take about 7 hours. Such robes were commonly embroidered with 25 to 30 stripes, so the process of beading this piece could have easily consumed 150 to 200 hours. The production of this article of formal dress is a significant artistic achievement but does not rival the labor invested in a complement of Crow equestrian gear.

Certainly, it is distinctly possible that few, if any, ethnic groups have devoted more time, energy, and talent to the decoration of horse gear than Apsáalooke women, particularly during the classic period (ca. 1870 – 1910). Their 200-year-old tradition of artistic excellence has persisted to this day and is still inspired by the distinctive style of beaded art for which their 19th-century ancestors are so renowned. Louella Johnson, an Apsáalooke artist who participated in the 2006 John Molloy Gallery exhibition with Della Big Hair, says that her predecessors were “very proud of who they were, and it shows in the [artwork that they produced. Contemporary beadworkers] are bringing back the old-time designs.” Their work is also inspired by tradition and remains an ongoing source of pride for the Apsáalooke people.

No Comments