23 Jul Artist of the West: Painting the World with Wonder

INSIDE A CENTURY-OLD BRICK FARMHOUSE near Rosebud, Mont., Mary Ann Cherry’s mother Winnie was always busy with handiwork. She crocheted rugs from her own designs and painted faces on the dolls she made from fabric. As Christmas neared, she crafted delicate paper ornaments. The year she decided to paint in oils, Mary Ann turned 8. The venture posed a conundrum for Winnie: what to do with the child. So she handed Mary Ann a canvas and a paintbrush and the two painted together in the dining room. Mary Ann’s father, Bill, encouraged his daughter: “Keep drawing and painting ‘til you’re as good as Charlie Russell, honey.”

Mary Ann listened. She studied art at Montana State University in Billings and although she didn’t graduate, she continued honing her skills as an artist. She made her first sale at a show in Havre, Mont.. Now, at age 58, she says of that milestone, “Somebody has an old oil painting in the attic of ducks settling onto a pond. I was ecstatic to sell it for $35. It was probably a direct copy of an old calendar photo because, at that time, I didn’t know better.”

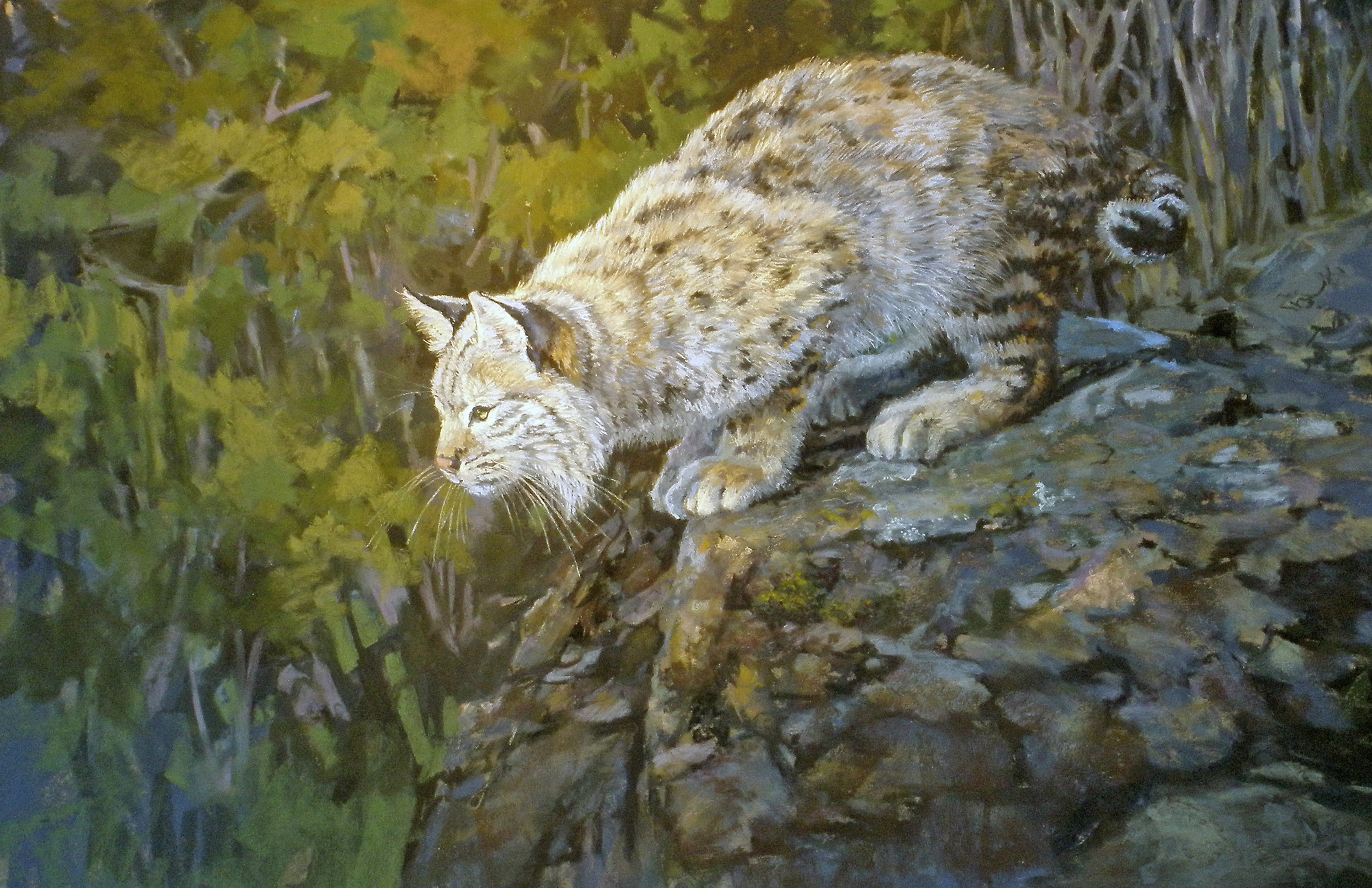

Since then Mary Ann Cherry has emerged as an award-winning painter. She’s learned to recognize the moods, emotions and subtleties of her subjects and express them on canvas. She doesn’t travel far from her Idaho Falls home, near the Snake River, to find subject matter that captures her imagination and motivates her to work with her brushes. Her paintings, mostly oils and pastels, move in Western themes, from wildlife to Native Americans to livestock to farmers and ranchers. She describes her style as blending traditional and impressionistic techniques that infuse her paintings with vitality and fresh concepts.

“My work has a realistic quality from a distance, with a definite looseness of brush or pastel stroke when viewed closely,” she explains. “When I began painting, I was tremendously excited about the vivid color, strong brush strokes and movement in Oleg Stavrowsky’s work. I still am. I try not to use the tired old clichés you see in many galleries. A bit of imagination goes a long way in making a piece of artwork uniquely your own.”

More than style or medium, Cherry’s intimacy with her subject matter endows her paintings with spirit and emotion. Her compositions and use of color create movement, dimension and depth. “I plan eye path and composition in a way I hope will lead the viewer through my painting so they can see, feel and interpret the subject in the way I do.” Cherry brings to life familiar scenes in the West: as in Second Trip Across, the cowboy looks relaxed and comfortable astride his horse. He’s strapped silver-colored antlers atop the mule’s pack. We can sense his introspective celebration of a successful elk hunt. We almost feel the equines’ movements and hear the water’s heaving surface pressing against their legs as they ford the river. “I was raised near the Yellowstone River so I love adding an element of water to my paintings,” Cherry explains. “Water is a familiar subject and somehow adds a lot of life. I painted this piece for fun since several men in the family hunt elk.”

When we study the painting more intently, we see the cowboy’s faith in his horse’s poise and athleticism. When we understand their interdependent relationship, we see the painting in its fullest form. “The key to creating a great painting is hard work and caring enough about the quality of your artwork to continue to learn and grow,” Cherry says. “We’re never done learning and improving. It’s wonderful when someone likes a painting well enough to purchase it, but I would paint even if nothing ever sold. It’s personal satisfaction for me.”

In a work devoted to horses, The Politicians, Cherry presents the rear ends of saddled and picketed horses. “I would say horses are my favorite subject to paint,” she says. “I was one of those little girls who said every Christmas, ‘Please, Santa, bring me a pony.’” She’s captured the horses’ languid movements as they wait, the lazy swatting of a tail, the way the light plays on their coats. These details aside, Cherry characterizes The Politicians as “a high contrast piece of a bunch of horse behinds” and quips, “the work is appropriately titled.” She goes no further. Brush political connotations aside and view the painting again. Other possibilities arise. The painting lets us wonder: Who rides those horses? Is it dudes visiting a resort in the contemporary West, or is it cowboys working a ranch a century ago?

Cherry and her husband, Bob, take trips searching out subject matter for photo references. Sometimes inspiration happens at home, as in Aleut Baby Moccasins. In this work she’s not portraying Native American footwear from the past, but beautiful objects from her childhood. As a little girl in Kodiak, Alaska, she toddled around in the intricately beaded moccasins she now portrays on canvas. Contemplating the moccasins from a textural, visual perspective, Cherry honors an Aleut Indian’s brilliantly colored handiwork upon an animal pelt with natural colors shifting from snow white to lead and bronze.

An increasing number of group and solo exhibits reveals Cherry’s emerging presence on the Western art scene. She’s created several new works for summer exhibitions at the Clymer Museum in Ellensburg, Wash., and the Olaf Wieghorst Museum in El Cajon, Calif. Her work is as good as winning three awards — Best of Show, the Foundation Award and Best Pastel — at the 2007 Phippen Museum Western Art Show juried competition in Prescott, Ariz. Of this accomplishment she says, “I was absolutely so delighted I could hardly breathe.” She’s as good as being one of three women given Master Signature Status by the Women Artists of the West.

As accolades and name recognition come to her, Cherry sometimes takes a step back. She looks to the Rosebud farmhouse where her mother handed her a paintbrush and her father urged her to be “as good as Russell, honey.”

- “Second Trip Across” | Pastel on Canvas | 21.5 x 31 inches

No Comments