01 Feb Local Knowledge: The Hearth Light and Fire of David James Duncan

It’s midafternoon in October, and a bonfire is burning behind our house. With me is David James Duncan, revered Montana author, storied activist, and one of the deepest spiritual and ecological minds of our time. He’s just finished a forthcoming novel, Sun House, a sweeping 1,100-page odyssey through the American West portraying what he calls “our biological and spiritually inescapable realities and the love and justice they demand.”

“I tried to stick to a more practical length, but the state of a world in which problems are no longer political but epic, overwhelming, mythical, left me pining to pen an epic in what the praise poet Anne Porter called ‘an altogether different language,’” he says. “I wanted this read to feel like walking El Camino in Spain, or the Pacific Crest Trail, or taking a month-long spiritual retreat in a place far from the nearest asphalt and fumes.”

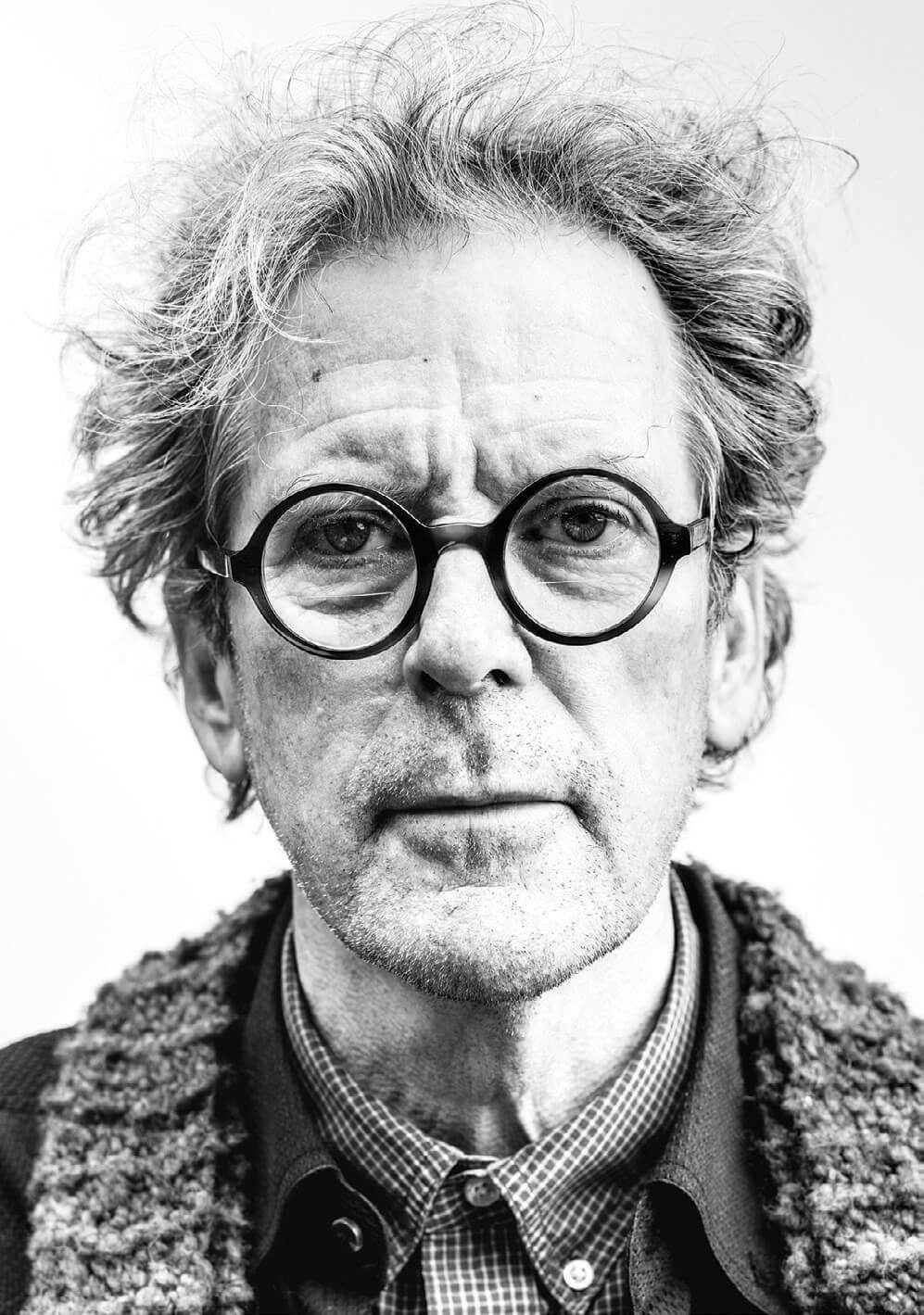

How my audience with Duncan came to be is a separate story, begun around a much earlier fire — or an earlier reverberation of this same fire warming us today, friendships being no different than flames. Huddled behind us are 12 tamaracks raining amber needles like embers into our laps — as if they too were a fire — as a towering broadleaf maple drops leaves like dinner plates the color of the sun. It’s cold out, such that we’re sitting snug to the flames. Nearby is a small and nearly dry spring-fed stream called Lost Creek, its water diminished by four unprecedented summer months without rain. I’m in a hooded fleece zipped tight to my chin. Duncan wears two long-sleeve collared shirts with a craft-knitted blue scarf horseshoed around his neck. “My daughter Celia made it,” he says, wearing it like a hug. Duncan says he wrote Sun House as a gift to his daughters, and all the generations facing the vast and the

Carson Artac

overwhelming. Our challenges, he says, have moved far beyond the political. “The world situation is darkly mythic now; epic. And requires a collectively mythic and epic response.”

“‘Nothing, having arrived, will stay,’” I remark, quoting a Wendell Berry poem. “‘… And yet this nothing is the seed of all — the clear eye of Heaven, where all the worlds appear.’” It’s a poem resonant within the pages of Sun House. Inside the narrative is a sense that the womb of Earth herself harbors a smoldering warmth that cannot be extinguished, as if a maternal force hidden in the dark nothing, beneath the dirt, is waiting to become known.

“One of the most unusual things about my life,” Duncan says, “from the time I was 20: I’ve had many friendships with wise old women, and a preference for the feminine expressions of wisdom, ongoing to this day. I drew on Julian of Norwich in The River Why, and visited her home city when I was just 17. I draw on Julian again in Sun House, saying, ‘Just as God is our Father, so God is our Mother.’ Toxic masculinity has, for centuries, driven our engagement with Mother Earth in exactly the wrong directions; I heed wise women facing the direction of life, not money. As our Muscogee Nation U.S. Poet Laureate Joy Harjo wrote, ‘Remember the earth whose skin you are.’”

For the better part of my life, Duncan has been a treasured companion; for years now in person, far longer in his body of work. Like every Pacific Northwest river kid Huck Finn wannabe, at age 16 I wanted to be Gus, Duncan’s protagonist in The River Why.

Duncan finished that book in 1979, when he was just 27, and it was published in 1983, when he was mowing lawns for a living in Portland and driving a Dodge Coronet with two smashed quarter panels and a door that wouldn’t open. Living in a $100-a-month cabin on an urban creek, finger-pecking at a typewriter and without an agent to his name, Duncan found his unsolicited manuscript rejected by every publisher in the country, until Sierra Club Books changed their nonfiction-only policy and made The River Why their first novel. Now, nearly 40 years later, it’s still in print and widely considered a classic.

Duncan followed up in 1992 with another novel, The Brothers K, an 800-page effort he spent seven years writing, which portrays a Vietnam-era American family broken for the same reason families break today, pieced back together with deep understandings and heroic acts of forgiveness. The Brothers K earned Duncan widespread acclaim and international attention; ever relevant, it too remains in print.

To say Duncan has been prolific in the three decades since The Brothers K is an understatement, but much of his work took the form of public speaking and activism. During those decades, he published three collections of essays, including the National Book Award-nominated My Story as Told by Water, and co-authored two activist-response books — Citizen’s Dissent, written in 2003 with Wendell Berry, and The Heart of the Monster, with Rick Bass — while also giving some 50 talks in close to as many cities.

In 2010, The Heart of the Monster was conceived, written, and published in a span of less than three months in a heroic attempt to stop ExxonMobil from turning 1,100 miles of Montana’s scenic byways into a primary transportation corridor for Alberta tar sands oil via river-routed roads, including the one that passed directly in front of Duncan’s house and home water. The proposed transportation corridor would have provided passage for articulating trucks so massive as to be almost unbelievable (both larger and heavier than the Statue of Liberty) alongside five iconic Western rivers. The book required tremendous personal courage from both Bass and Duncan and, in the end, their cause prevailed.

“We went head-to-head with ExxonMobil at the time of their greatest power, and thousands of local heroes share the credit for stopping them,” Duncan says. “With our book, Rick and I were, so to speak, the Paul Revere figures yelling, ‘The monster is coming! The monster is coming!’ It’s still hard to fathom how our side won this fight to protect the Clearwater, Big Blackfoot, Nez Perce Trail of Tears, and other national treasures from being turned into tar sands’ tentacles.”

All the while, amidst these big and involved writing and activist efforts, Duncan continued to produce stand-alone essays, published in magazines, journals, and over 40 anthologies including The Best American Essays, The Best American Spiritual Writing (appearing five times!), and The Best American Sports Writing. He also appeared in numerous documentaries, and both The River Why and The Brothers K were adapted and performed on stage to sold-out runs at the acclaimed Book-It Repertory Theatre beneath Seattle’s landmark Space Needle.

Most recently, Duncan edited, curated, and wrote the forward to One Long River of Song, a vast and heartfelt collection of writings by his close friend and much-loved Portland-based writer, Brian Doyle. Published in 2019 by Little, Brown and Company (which also published Sun House), One Long River of Song is already in its second printing.

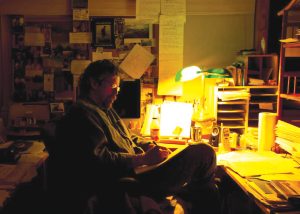

Yet, for the past 14 years, beyond all that body of work, Duncan has primarily been seated in Montana at the table of Sun House, putting in 6- to 12-hour writing days, taking breaks only for birds, mountain walks, and an occasional cast when the fishing is good.

His vast, multi-generational novel is set against the mountains and rivers of the West, and told through the perspective of multiple narrators. It’s the contemporary story of rural Montanans on a twice-failed cattle ranch joining forces with a few urban refugees who swallow their city-mouse-versus-country-mouse misgivings. “I’ve seen countless op-eds calling for a change of consciousness if humanity is to survive,” says Duncan. “I’ve seen zero op-ed descriptions of what this consciousness looks, feels, tastes, sounds, and lives like from day to day. That’s the void Sun House sets out to fill, because that’s the void plaguing countless human lives.”

While the community and characters in the novel are fictional, the implications of their viability are pertinent, pressing, and based on the very best things Duncan has seen. “I’ve come to believe only love and justice can work this mess out,” he says. “I still see a path forward.” He’s written of this path with the urgency of a fireman entering a house ablaze, and with the calm wisdom of one who’s entered conflagrations before.

David James Duncan, wading the tall grass in a not-to-be-named spring creek in western Montana, adheres to the adage sacred and secret: The best fishing spots are kept close to the vest.

“Needed changes of consciousness is the through-line in my fiction,” Duncan says. “And it will remain a through-line. An activist I admire, Charles Eisenstein, recently said why in an essay titled, ‘On the Great Green Wall, and Being Useful’: ‘To heal the world, people must no longer be treated as standardized producers, functionaries, or medical objects in a global industrial system. Not only does this alienate them from the local knowledge and relationship needed to heal the places where they live, it creates legions of superfluous human beings.’”

“Beginning with those wise, older women [I] befriended when I was young … most of the couple hundred people I’m closest to lead lives that are not only not superfluous, they’re heroic,” Duncan adds. “I reference scores of these people in the epigraphs that open each chapter of Sun House, like these words from Meister Eckhart: ‘When the soul wants to experience something, she throws an image out in front of her, then steps into it.’ This statement reminds me of the way you and your firehouse brothers step into a fire, Jimmy: soul first, and I so admire that.”

Adding logs to the fire, I mention a paradox I’m well acquainted with as a fireman. “Inside a house on fire, it’s complete darkness — ink black,” I say. “So, we navigate by feel and sound, searching for life and for the seat of the flames, both felt well before they’re seen, inching toward them until a sun appears. … We don’t put water on the fire until we’re nearly on top of it, where it’s the hottest. The only way this is accomplished is with love, and it can’t be accomplished alone. Firefighters can only navigate here in unison — with literal, physical contact with each other — and with a complete change of consciousness, turning entirely away from the self.”

As dusk arrives, and the shadows from the sun have all but disappeared, we move even closer to the fire, and I remember something Duncan’s friend Barry Lopez wrote before passing: “There are simply no answers to some of the great pressing questions. You continue to live them out, making your life a worthy expression of leaning into the light.”

Duncan burned the midnight oil writing and sorting at his desk during the earliest stages and longest days of Sun House. Photo Courtesy Of David James Duncan’s Personal Archives

This, Duncan has done his whole life. Even now, surrounded by darkness save the glow of the fire and its reflection against his face, his heartfelt truths and compassion are physically felt and visibly radiant. I can see them. The trees see them, as do the lost creeks and the hundred-billion suns in the night sky above us. Listening to him talk next to the fire, it strikes me that Duncan, now 70, has become an elder, a guide comfortable both in this world and the other, the inner. His stories read like gospels — where the word is the water and where Duncan is carrying it with cupped hands.

“What’s next?” I ask, to which Duncan replies with the expected itinerary of an author with a completed book — the back and forth with the publisher, book tours, readings, etc. — and he has other works on the backburner, too. But that’s not what I’m asking about and he knows it.

“In response to Barry’s insight that the great questions have no answers, I find the unanswerable to be a reminder that I was born lost, but in creeks and rivers began to be found,” he says. “Watersheds remain a place of pilgrimage, wild salmon an interior compass, rivers prayer wheels, industrialized rivers blues tunes, dying birds prophets and guides, wild places as small as weeds blooming in the cracks of city sidewalks a momentary home.”

Jimmy Watts lives in Bellingham, Washington with his wife, their two sons, and a retriever. An award-winning writer, Watts’ work has appeared in American Flyfisher, The Drake, and Orion Magazine, among others. He is also the craftsman behind Shuksan Rod Company (split cane bamboo fly rods) and has been a firefighter in downtown Seattle for the past 22 years.

No Comments