05 Aug Local Knowledge: Backcountry Blacksmith

Nestled between the Teton and Big Hole mountain ranges in Teton Valley, Idaho, Alexandra Paliwoda’s Backcountry Blacksmith shop is aptly named, with a nod to both her chosen profession and the natural themes that her metalwork embodies. Elements of the journeys she’s experienced in the wild and the places she’s lived throughout her life also inspire her work and are present in many of the items she sells. The Hand-Forged Mountain Ridge and Copper River knives, for instance, depict scenes from Alaska’s Copper River and an array of mountain ranges. “I try to typically name the designs on these knives after places I either like, or mountain ranges, or the natural places that I think are just astounding,” Paliwoda says.

Horseshoes are integrated into many of Alexandra Paliwoda’s pieces, including these wind chimes, representing her time working as a farrier.

Paliwoda was already familier with metalwork when she was living in a cabin near the small town of Tok, Alaska. There, she worked as a farrier, caring for horses’ hooves and shoeing them — a skill she acquired while attending Montana State University’s Farrier School. As the only farrier for hundreds of miles, it wasn’t uncommon for her to spend hours driving to faraway locations to shoe a single horse, using her skills to create custom therapeutics when needed.

As a female farrier, Paliwoda faced sexism at times, and she found that when she changed the name on her business cards from Alexandra to Alex, she received a significant increase in phone calls inquiring about her services. When she answered the phone, sometimes people would ask for Alex and expect to speak to a man. “I would say, ‘This is Alex,’ and then they were caught,” she recalls. “Most people weren’t rude enough to hang up, but a couple did.”

Since a forge is a central part of blacksmith’s shop, the work is often intensely hot and physically laborious.

A back injury eventually forced Paliwoda to move away from working with horses, but she loved the metalwork aspect of the profession, and transitioning to being a blacksmith was a natural fit. But blacksmithing also takes a toll on the body. Injuries, blisters, and general wear-and-tear are hazards of the job, which can be hot, physical, and laborious.

Due to this, in her workshop on a side street in downtown Driggs, Idaho, in addition to hands-on work, Paliwoda takes on most of the design work, and she has a team that helps to create everything from large-scale pieces to smaller gift items that are sold online. They also produce custom pieces, such as signs for local businesses and elaborate ornamental gates for homes. Horseshoes are common in her designs, reflecting her time as a farrier. She uses them in wind chimes, trivets, and even wine racks.

Paliwoda’s Backcountry Blacksmith shop, which is located just off Main Street in Driggs, Idaho, produces everything from wine racks and wind chimes to large customized installations.

Paliwoda designed her Teton Valley home on her own, transforming it from an old three-bay garage that sat unused on 4 acres before she bought the land. She lives in one-third of the space in a studio apartment that she created with vaulted ceilings, a deck with a hot tub, and, not surprisingly, plenty of steel accents, such as a custom railing she recently installed that depicts an elaborate mountain panorama, complete with trees, foothills, peaks, and a rising sun. The rest of the building serves as a packaging area for shipping Backcountry Blacksmith inventory.

- Hand-forged Takhinsha Ulu Knife

- Sushi serving set

- Gold leaf hooks

- Spiral scroll salad tongs

Her current home isn’t the first living space that Paliwoda customized to meet her needs. Long before she settled in the Teton Valley, she built her own cabin in Alaska on a parcel of land that was thick with black spruce trees. Growing up on a farm, she became self-reliant and skilled in construction — when she was just 13, she and her 10-year-old brother built their first barn. Paliwoda also knows how to use heavy machinery, so when it was time to dig out space for a septic tank and electrical lines, she simply borrowed an excavator to do the digging, later using a loaned front-end loader to backfill.

Her mother worked in architecture, so Paliwoda had learned a few things about designing a space, and she drew upon that knowledge when it came time for her to build. One of her priorities was maximizing sunshine, which is scarce in Alaska for much of the year, so she positioned the cabin to take in as much natural light as possible and added plenty of windows. She did the majority of the work on the cabin herself, with her sister and friends helping at times, and brought in an electrician to tackle some of the more complex aspects.

Thankfully, these days Paliwoda doesn’t run into the issue of sexism as much as she did during her time in Alaska, and she finds that people of all genders are interested in her work. And she’s passionate about the work; she loves the challenge of carefully crafting each piece, whether it’s a customized ornamental railing or one of the more than 10,000 horseshoe hearts she’s personally created during her career.

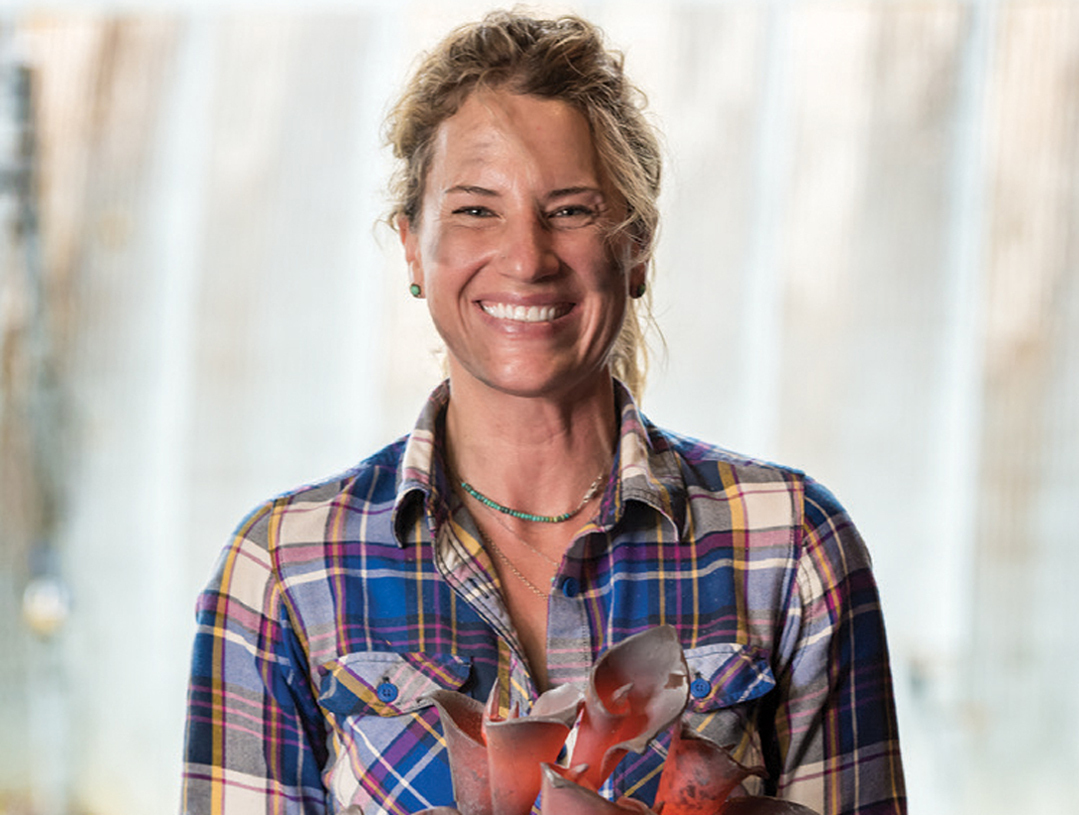

Paliwoda and her team at Backcountry Blacksmith create distinctive pieces that incorporate elements of nature.

“There’s such freedom with creativity,” she says. “I love the challenge. I love surprising people with something different. I have no problem creating something traditional or contemporary, but I really love the creative aspect and the challenge in what I do for work.”

No Comments