01 Aug Inspired

In 2009, John Isaiah Pepion was involved in a near-fatal car wreck that left him homebound for many months. During his recovery, he began drawing daily to pass the time. Pepion had always enjoyed art growing up, starting with watercolors and whatever canvas he could find, but he would only draw periodically and admits he only took it seriously after the accident.

His initial inspiration came from his great uncle, Victor Pepion, whose murals cover the Museum of the Plains Indian in Browning, Montana. “My great uncle made what was categorized as ‘flat Indian style’ art, which was popular in the ’60s,” Pepion says, adding, “I had an old computer desk with minimal supplies, but it helped me develop my own personal style.” This was his relationship with art until 2011 when he chose to pursue it professionally. “I didn’t think I was an artist until I made that decision for myself.”

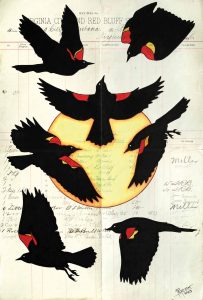

Sky Raiders | INK AND COLORED PENCIL ON ANTIQUE LEDGER PAPER | 17 X 11 INCHES

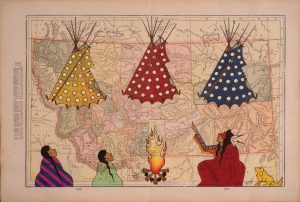

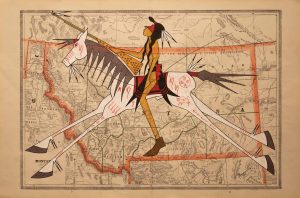

Art is significant for Native Americans because it has allowed them to hold onto their history. Origins, war stories, significant events, dreams, and visions have all been expressed through pictographs and petroglyphs, etched into rock as a timeless reminder of those who came before. Over time, this style evolved into winter counts on elk and buffalo hides depicting a warrior’s life and accomplishments.

During the Reservation Era of the mid 1800s, many Plains Indians refused to conform to the Western way of life. Because of this, they were sent to Fort Marion in St. Augustine, Florida, where they were imprisoned for three years. Guards gave the prisoners old or blank ledger paper, colored pencils, and crayons, and the prisoners began depicting their previous lives on paper, sketching war stories, dreams, raids, hunts, and battle scenes. When tourists began visiting the prison, the warriors started selling their ledger art pieces. Many of these old works are highly sought after today, fetching hundreds of thousands of dollars at auctions and holding pride of place in museums nationwide.

Story Night | INK, COLORED PENCIL, AND ACRYLIC ON ANTIQUE MONTANA MAP | 13 6 ⁄8 X 21 3 ⁄4 INCHES

Pepion grew up on the Blackfeet Nation on the east side of Glacier National Park in northern Montana. Surrounded by picturesque mountains, open plains, and centuries of Blackfeet tradition, Pepion was fortunate to be born into a family of artists, which he says profoundly influenced him. This inspired his artistic explorations and grounded him in his culture and traditions.

Pepion’s artistic journey led him to ledger art, which is now known as Contemporary Ledger Art. While exploring museums for inspiration, Pepion noticed that curators referred to the style as “Plains Indian graphic art.” This term resonated with him, as it encapsulated his creative approach to art. “I don’t limit myself to ledger paper; I turn any canvas I touch into art. That’s why I use the term for everything now,” he explains.

Pepion works on a piece in his home studio. Titled Wild Bronc, the work was part of a group exhibition at Art Gotham in New York City called Rodeo & Rebels: An Ode to the Wild West. Photo by WHITNEY SNOW

From 2002 to 2004, Pepion attended the United Tribes Technical College in Bismarck, North Dakota and earned his associate of applied science in art and art marketing. He then attended the Institute of American Indian Arts (IAIA) in Santa Fe, New Mexico from 2005 to 2008, receiving his bachelor’s degree in museum studies. During this time, Pepion’s career as an artist experienced its first significant growth.

Pepion’s buffalo design pays tribute to the enduring significance of the buffalo in Plains Indian life, symbolizing its power and sacrifice. With this silk scarf collaboration through Eighth Generation, Pepion’s design mimics the ledger paper on which Plains Natives painted. Photo by WHITNEY SNOW

Pepion recalls when a college roommate gave him some old ledger paper in 2007. “Until then, I had been using watercolor and whatever canvas I could find. I had never had access to ledger paper, so this was an exciting new medium for me to explore.” He invested in a set of colored pencils and started drawing. Initially, it was challenging to transition from paint to pencil, and he says finishing two pictures took him a long time. Still, he persisted throughout his schooling and continued after graduation. He began selling his art for extra money. “I didn’t know my worth back then,” he says, “so I would sell small 5- by 7-inch pieces for around $20, usually to buy gas or food. I didn’t understand having a workflow or an inventory and continued to work odd jobs while selling artwork on the side.”

War Lodge | INK, COLORED PENCIL, AND ACRYLIC ON ANTIQUE MONTANA MAP | 23 3 ⁄8 X 17 1 ⁄4 INCHES

Pepion was invited to exhibit his work at a show for students of the IAIA at the Museum of Contemporary Native Arts during the 2010 Santa Fe Indian Market. He gathered all the small pieces he had and set them up. This showcase proved to be a transformational opportunity for Pepion: He sold out of everything and was offered an art fellowship from Santa Fe’s Wheelwright Museum. A significant boost for his art career and confidence, the fellowship also provided the money necessary to purchase professional supplies and materials for the work to come.

Pepion participated in the Out West Art Show in Great Falls, Montana for the third year in 2024. The show includes over 200 artists, though only a few of them are Native, motivating Pepion to participate annually. Photo by WHITNEY SNOW

On the heels of that success, Pepion was invited to participate in his first art show in Santa Fe, alongside two other ledger artists, in 2011. He considers this show a turning point in his career; the positive feedback he received encouraged him to pursue art professionally. “People wanted to see me succeed, so other artists started giving me ledger paper,” Pepion says. “I received ledger paper from antique stores and started getting invited to collaborate on more art shows.”

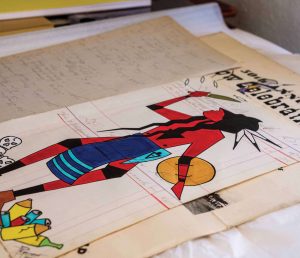

Kutoyis (Blood Clot) is a Blackfoot superhero who slays numerous monsters. In Kutoyis Fights Addiction, he is slaying addiction. Photo by WHITNEY SNOW

Subsequently, he was selected to participate in his first art market, the First Peoples’ Market in Butte, Montana, held during the annual Montana Folk Festival. In 2012, he put on his first solo art show at the Museum of the Plains Indian in Browning. In 2018, he was invited to collaborate with Eighth Generation, an Indigenous-founded company based out of Seattle, Washington whose slogan is “Inspired Natives, not Native Inspired.”

War Horse | INK, COLORED PENCIL, AND ACRYLIC ON ANTIQUE MONTANA MAP | 13 5 ⁄8 X 21 3 ⁄4 INCHES

Since his first solo art show, Pepion has exhibited nationally and internationally, with work in the permanent collections of the Plains Indian Museum at the Buffalo Bill Center of the West in Cody, Wyoming, the Library of Congress in Washington, D.C., the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History in Washington, D.C., and the Autry Museum of the American West in Los Angeles, California. This summer, he was involved in Grounded, a traveling exhibit throughout North America, which made its last stop in Washington, D.C. in June and was curated by Robert Martinez for Caravan.

Though his international and national art shows have been successful, Pepion says his most memorable work is in his home state of Montana. When reflecting on his success, he’s most proud of his relationships with local galleries, such as FoR Fine Art in Whitefish. “We are honored to show the work of Indigenous artists like John in the galleries,” says gallery founder Derek Vandeberg. “John’s work is vibrant and more stylized than other ledger artists. His imagery’s graphic aspects resonate with our audience here as our market trends more modern and less contemporary. John’s iconography uniquely, accurately represents his tribe’s history and mythology; he describes his work as a vision of Native people living their traditional lives, but on paper. With so many artists romanticizing the mythos of the West, and particularly the history of Indigenous people, John’s voice is especially authentic.”

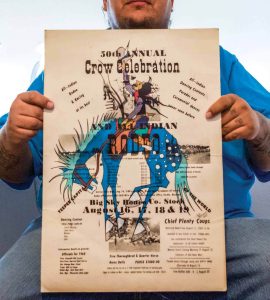

Tribute to the Indigenous Cowboy on a vintage Crow Fair Poster was created for the Rodeo & Rebels: An Ode to the Wild West exhibition in New York City this past spring. Photo by WHITNEY SNOW

When discussing his artistic process, Pepion says he can’t draw while feeling negative. “I have to have positive feelings and thoughts while creating my artwork, and I find that I’m most productive in the morning and throughout the day. I also have a better sense of time management than I did earlier in my career. Before, the pencil sharpener would be going all night. Now, I allow myself time to decompress and step back if needed.”

When asked how it feels to be a nationally and internationally recognized artist, he says, “This journey has been a humbling experience. I’ve been offered many opportunities to move out of state but choose to stay in my community. I help other artists as much as possible, share knowledge, and contribute to the community through speaking engagements. Most importantly, I am learning the ceremony and traditions of the Blackfeet. Living away from that would bother me. I wouldn’t be where I am now if it weren’t for my community.”

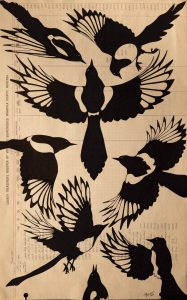

Uplifted | INK ON ANTIQUE LEDGER PAPER | 17 X 11 INCHES

It’s clear that he doesn’t take his success for granted. He’s particularly thrilled about an upcoming art show, Far West, a pop-up exhibition co-curated by artist Mark Maggiori on September 9 and 10 at Arcadia Contemporary in New York City. “I am the only Indigenous artist they invited out of 19 artists. I have never been to New York, so I look forward to this show.” An undeniable force in the art world, Pepion believes that the time has finally come for Indigenous people to have a voice, to insist on a presence that accurately describes and defines their cultural history. “Isn’t it time our people be allowed to tell their own stories rather than having others interpret our history for us?”

Whitney Snow is a documentary photographer dedicated to capturing stories depicting the emotional connection between Indigenous people and their environment. She focuses on narratives illustrating Indigenous communities’ struggles to preserve their way of life, including efforts related to environmental and cultural conservation and language revitalization.

Joan Robinson

Posted at 17:42h, 07 AugustWonderfully written article! Loved the photos!