01 Aug In The Grip of the Wild: Artists of the Northern Rockies draw on nature to reveal the nature of art

It’s widely acknowledged that nature inspires art, but the adage is rarely transposed. Yet, art through the ages has certainly left its imprint on nature: in gardens and dwellings, in water features and public sculptures, in designs and in deeds.

The relationship between artists and nature spans millennia, from the paintings of wild creatures in the Chauvet cave in France to ancient African masks, from the totem poles of the Pacific Northwest First Nations to Fan Kuan’s Chinese landscapes, John Constable’s painted praises to the British countryside, and beyond, up to contemporary times. The development of art’s relationship with nature is founded on the principle that various forms of art, including painting and poetry, are interpreted as attempts to imitate nature, even improve it.

PANCHO AND LEFTY | Jim Bortz | Oil on Board | 30 x 30 Inches

While nature and its creatures are mostly seen directly, the indirect and unique depictions when viewed and portrayed through an artistic perspective may be equally important. Mutually beneficial, the relationship might even be described as necessary for humankind’s broader understanding, inspiration, and solace. “The world is too much with us; late and soon/Getting and spending we lay waste our powers/Little we see in Nature that is ours,” laments poet William Wordsworth in the sonnet whose title is taken from its first line.

HIGHER GROUND | Kathryn Mapes Turner | Oil on Rag | 12.25 x 12.5 Inches

An examination of the interplay between the wild world and its inhabitants, and the arguably tame interior world where the majority of people reside, is among the aims of exhibits at the National Museum of Wildlife Art in Jackson Hole, Wyoming, where animals and their environments are central subjects. At a time when human activities are affecting nature and its creatures in increasingly negative ways, an exploration of that relationship through art is particularly compelling.

Bonheur & Beyond: Celebrating Women in Wildlife Art, an exhibit in place until mid-August, was arranged by museum art curator Tammi Hanawalt to amplify the attitudes that a group of critically acclaimed female artists bring to the genre. “Wildlife art is often considered Western art because big game animals and exploration have long been associated with masculine pursuits,” Hanawalt says. “What we’re seeking is an interpretation of wildlife that is defined by artists who bring a different, but equally valid, set of values and cultural experiences to the subject.”

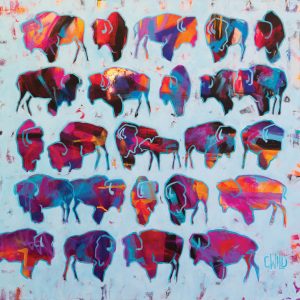

RENDEZVOUS IN COLOR TWENTY FIVE | Carrie Wild | Acrylic & Gold Leaf | 36 x 36 Inches

Given that female artists were largely excluded from the canon until the 1980s, Hanawalt felt that showcasing those artists, past and present, was overdue. “We are adding the works of women who could hold their own in any forum, whose work is in the top tier of the genre, and who fearlessly explore their relationship with nature and its creatures,” she says.

Kathryn Mapes Turner is one of the artists in the exhibit. The award-winning painter was born and reared on a ranch inside Grand Teton National Park, where she woke daily to a view of one of the nation’s most celebrated mountain ranges. Turner has always sensed that she and the landscape were inextricably linked. “From early on, the landscape claimed me as her own; the beauty of this place has touched me at a very deep level for as long as I can remember,” says Turner. “Art became the practice of expressing my gratitude; my paintings are my love letter to the natural world.”

THE WILDHEART SINGS | Kathryn Mapes Turner | Oil on Panel | 11 x 14 Inches

After the Rain, a 48-by-48-inch oil by Turner, illustrates the nature of that love. The picture of a bull moose that merges with a watery world is a statement of idea in a material environment. Turner’s serenity in light of that conundrum is seemingly effortless, perhaps because hers was an upbringing in which the two were not separate. Turner’s father, a wildlife biologist by training, taught his daughter the ways of the Teton wilderness, cultivating in her a sense of reverence.

The two worlds collide in the human influence on the land and its animals, a collision Turner has keyed in on. Moose in Jackson Hole, for example, find highways intersecting their habitat and migration routes, leading to accidents in which the animal is invariably the loser. “I am very concerned about how the natural world is doing and what our impact is on it,” says Turner. “I now feel a sense of mission. I want to bring to life in anyone who sees my paintings that sense of love and reverence. I want art to draw in the viewer and give them a chance to pause and be present and connect to what we all find beautiful, what we all hold dear, what we all value.”

AFTER THE RAIN | Kathryn Mapes Turner | Oil on Rag | 48 x 48 Inches

Turner sees in art a mirror of nature, in its object and its spirit. “Everything in painting is about connectedness: one value to the next, one shape to the next, brushwork connected to other brushwork,” she explains. “Similarly, there is nothing in nature that is created without purpose and which is not related. Since we are part of nature, our actions or inactions make a difference.”

Japanese artists of past centuries underscored that principle with spare pictures that ultimately could be reduced to fragile lines which, paradoxically, could bear up under the pressure of weighty meaning. Turner’s Higher Ground reflects that pairing; it is a painting of mountains veiled by mist and trees blurred by rain, yet reflected clearly in still waters.

DRY AS DUST | Jim Bortz | Oil on Board | 18 x 24 Inches

Conversely, The Wild Heart Sings depicts a robin perched on a branch, reflecting on matters unknown and unknowable. Turner says she chose to paint a bird — recognized by many and often taken for granted — in an unexpected style. “I wanted people to see something common for what it is: uncommon, full of vitality, and an object of wonder — all right there in your own backyard,” she says.

Wonder is also the way of Cody, Wyoming painter Jim Bortz, one of the artists featured in Western Visions, the September art show and sale at the National Museum of Wildlife Art. Lately, Bortz has explored a style that led him to use a palette knife for pictures of animals, allowing for bold textural lines that suggest low relief sculpture.

THE OPPORTUNIST | Jim Bortz | Oil on Cradled Panel | 18 x 36 Inches

Dry as Dust, an oil by Bortz depicting dried grasses trodden by horses in shared shades of brown, is a testimonial by the artist about how a natural scene can express the same period of suspension that creative people undergo just before a new style emerges. Like nature, art and artists evolve, and Bortz is no exception. “I felt I wasn’t getting better,” he says of the period before plunging into an exploration of thick brushstrokes. “I knew I needed to be brave and try something new.”

More at ease in the company of creatures and the outdoors than people and interiors, Bortz has cultivated a kind of monastic sense of separateness from a world of eternal busyness. He paints that which is infinite — as indicated by the possibilities in nature and a seasonal cycle that is replicated by all living things, which move from birth to death at a pace that is not of their volition.

DAYBREAK | Carrie Wild | Acrylic & Gold Leaf | 20 x 20 Inches

Bortz has a high regard for paintings that underscore their integrity by capturing an experience of the artist. He adheres to the discipline that selects as a subject only those creatures of nature and those scenes of wildness that the artist has actually observed. “I don’t allow myself to paint anything I haven’t seen; it feels disingenuous to me,” he says. “I want to convey through my art my experiences in the wild places of the Northern Rockies.” In the hands of a painter like Bortz, wildlife is imbued with high intelligence, honed instincts, and characteristics that act in harmony with the land. Bortz recalls laughing aloud while fishing in a stream where a hatch of insects at the water’s surface triggered a feeding frenzy among trout. Intent on catching a fish, he belatedly realized a grizzly bear had ambled into the fray. It stopped short and stared at the scene, incredulous, before lumbering away.

Bortz knows firsthand the value of contact with nature and he wishes the same, even if vicariously, for those who view his art. The Opportunist shows a red fox atop deep snow, apparently assessing potential prey below. Like those who view his paintings, Bortz is transported by observing the fox where the animal is in geography, but also in being.Such insights point to the value of nature and the striving, sentient life of creatures on the earth, in the air, and in the water. “There’s tension in the West where people are sharing the landscape with grizzlies, mountain lions, and wolves,” says Bortz. “But the closeness of predators that would just as soon eat you as look at you is part of what makes these places wild, and I don’t think that should ever change.”

Carrie Wild is likewise an artist who believes in the agency of animals that roam the arid and forested mountains of the Northern Rockies and the American Southwest. Wild, who has galleries in Jackson Hole and Santa Fe, New Mexico, grew up on a small horse farm in Michigan, where she spent spare moments riding, exploring forests, and acquainting herself with the ways and means of nature. Like Turner and Bortz, Wild feels a keen sense of respect toward animals in their environments and a kinship that comes from years of observation. “Being part of the world of wildlife, you have the responsibility to learn about those animals: why they are there, what they are doing,” says Wild. “When you’re on the landscape with wildlife, you’re part of nature. You see them and they see you seeing; you’re part of it.”

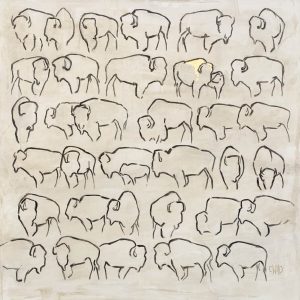

RENDEZVOUS THIRTY SIX | Carrie Wild | Acrylic & Gold Leaf | 36 x 36 Inches

Her art reflects the deep understanding — communion, even — that comes from constant encounters with creatures that, unlike humankind, appear at ease with their creaturehood and numberless days where what nature provides is sufficient.

Wild’s style evokes the vitality she finds in the world beyond the window, and her body of work, including pieces where blocks of color meet stylized bison or herds of horses, relies on her merging of realism and abstraction. Daybreak — a medley of color, form, and bison — demonstrates Wild’s break with tradition to achieve her distinct vision in acrylic and gold leaf. A more recent series of paintings, including Rendezvous Thirty Six, shows bison through line, in a technique that can be likened to Picasso’s animal line drawings, where absent details don’t detract from a creature’s essential self. In this, Wild invites viewers to share her passion for the animal subjects of her paintings. “I’m transferring that love for wildlife and for nature to that person.”

No Comments