04 Oct Images of the West: Theodore Roosevelt, from Medora to Gardiner

In early April 1903, grinning like a delighted schoolboy, President Theodore Roosevelt stepped off the train in Gardiner, Montana. He’d had plenty of experience in the role of conquering hero, but his attitude now was more that of a farmer harvesting a bumper crop, a father watching the success of his sons and daughters, or a hunter who had just acquired the ultimate trophy. He was seeing the fulfillment of his dreams.

The army officers charged with protecting Yellowstone National Park from poachers mounted Roosevelt on a spirited gray horse, for there could be nothing inferior for a president who had already taken his knocks as a Great Plains cowboy. Riding to Mammoth Hot Springs, his hunter’s eye immediately spotted the distinctive rump patches of the relatively tame pronghorns feeding near the park gate. And in the days and weeks that followed, a respite from Washington, DC, that took Roosevelt through Yellowstone and on to Yosemite, Roosevelt’s conservation ethic, solidified by his experiences as a Western hunter and outdoorsman, expanded even further. Things he said and did during this fertile time still resonate today, particularly with those who understand the link between hunting and conservation.

Roosevelt’s train ride west in 1903 was in stark contrast with his arrival at Medora, near what is now the Montana-North Dakota border, just 19 years earlier. Stricken by grief — his wife and his mother had recently died in his house on the same day — Roosevelt channeled the frenetic energy for which he was known into the establishment of a cattle ranch near Medora, Dakota Territory. The man who would later say, “The joy in life is his who has the heart to demand it,” handled his grief on horseback, a rifle scabbard under his knee, on long rides across undulating prairie searching for the pronghorn antelope that became preferred table fare for his ranch hands.

Always tuned to the birdsongs around him (as an ornithologist, Roosevelt could have stepped into a professor’s position), he would ever after associate the lilt of the meadowlark — three descending eighth notes, a pair of higher 16ths, then a lower resolving tone — with this crushing grief. But he handled it Roosevelt-style: organize, resolve, pursue. He seems to have applied Lady Macbeth’s advice from his favorite Shakespearean play, but in positive directions: “Screw your courage to the sticking place and [you’ll] not fail.” And, as in boyhood, his solace came through the natural world.

Much has been said about Roosevelt’s sickly childhood but too little about that child’s alter ego, something akin to the Energizer bunny in rotation with debilitating periods of illness. His boy’s bedroom reeked of bad attempts at taxidermy, along with odors from a menagerie of small, captive creatures — rodents, birds, and snakes in crude wooden cages — which he studied assiduously. Even from his childhood, hunting was never at odds with preservation. So it’s not surprising that his very first trip west in 1883 at age 25, a year before he rode out to establish his ranch, was in pursuit of one of the vanishing bison in the Montana-Dakota border country. He finally caught up with a jaded bull and managed, after considerable effort, to put him down, perhaps a rocky beginning to his life as a great conservationist but one that proved his grit outweighed his thick glasses and slight figure. After a wet snowstorm, waking up on the floor of a line shack in a puddle of icy water, his guides heard him say, “By Godfrey, this is fun.”

It was the big open country of Western Dakota and Eastern Montana territories that made Roosevelt a hunter, and one on the most basic level. From his autobiography:

Getting meat for the ranch usually devolved upon me. I always carried a rifle when I rode, either in a scabbard under my thigh, or across the pommel.

Often I would pick up a deer or antelope while about my regular work, when visiting a line camp or riding after the cattle. At other times I would make a day’s trip after them. In the fall we sometimes took a wagon and made a week’s hunt, returning with eight or 10 deer carcasses, and perhaps an elk or mountain sheep as well.

Many different horses, some good, some not so good, carried him on these jaunts. (He named one bad-tempered animal Sam Butler after a politician he disliked; the horse went over backward on him, breaking his collar bone. It could have killed him.) But a horse named for an Eastern spirit creature, Manitou, emerged as his favorite. It was Manitou, a smooth single-footer with nerves of steel, who carried him across the Little Missouri at flood stage, dodging floating chunks of ice. It is in photos pictured with this animal that I most like to study the young, Western Roosevelt, living the life about which he later said, “I would not have been President had it not been for my experience in North Dakota.” And much later, on a westward trip the year before his death, he looked out the train window at his beloved badlands and said, “The romance of my life began here.”

There would be more exotic hunts — Western safaris to the Powder River country, the Bighorns of Wyoming, the Slough Creek valley north of Yellowstone Park, the extreme northwest corner of Montana, and much later, after his presidency, the far reaches of Africa — but his roots were those of a Western meat hunter. Though his ties to wildlife in general were always strong, it’s clear that his first and last affection went to the animals humans could consume, and particularly, in Montana, the deer, elk, and antelope.

The experiences framed between these two key photos — Roosevelt with Manitou and President Roosevelt arriving in Gardiner less than 20 years later — indelibly stamped on Roosevelt his hunting-conservation ethic. That ethic contains two ideas that emerge through careful reading of such books as Hunting Trips of a Ranchman, The Wilderness Hunter, and others.

First, Roosevelt considered hunting to be a vital ingredient in the American national character. In his autobiography he wrote, “Hardy outdoor sports like hunting, are in themselves of no small value to National character and should be encouraged in every way. Men who go into the wilderness, indeed, men who take part in any field sports with horse or rifle, receive a benefit which can hardly be given by even the most vigorous athletic games.”

Second, Roosevelt and several of his most influential friends, such as conservation icon George Bird Grinnell, editor of Forest and Stream magazine and co-founder of the Boone and Crockett Club, made the argument that national parks should serve as breeding grounds for the animal species most vital to American hunters: elk, deer, antelope, bison, and to a lesser degree, bighorn sheep and mountain goats. Protecting animals from poaching inside Yellowstone and other national parks would assure a plentiful supply of these species. In 1903, such protection was provided by the U.S. Army, whose officers met Roosevelt at the train.

Roosevelt had been directly involved in the effort to protect the wildlife within Yellowstone, and his 1903 visit allowed him to see the bountiful success of his work. As president of the Boone and Crockett Club, he had lobbied Congress for action to protect Yellowstone from poachers. His efforts were rewarded in 1894 with passage of the Park Protection Act, which allowed for the military protection of Yellowstone. Now, in 1903, concerned about mountain lion predation on the pronghorn antelope in the park, Roosevelt conferred with the park superintendent Major John Pitcher about his decision to hire hunters with hounds to thin out the cougar population. He took joy in the work of former bison hunter Buffalo Jones, who had been hired to help the struggling bison herd regain a foothold. Bison had been imported from Montana’s Flathead Valley and from Texas to supplement the herd, and a viable breeding population was emerging.

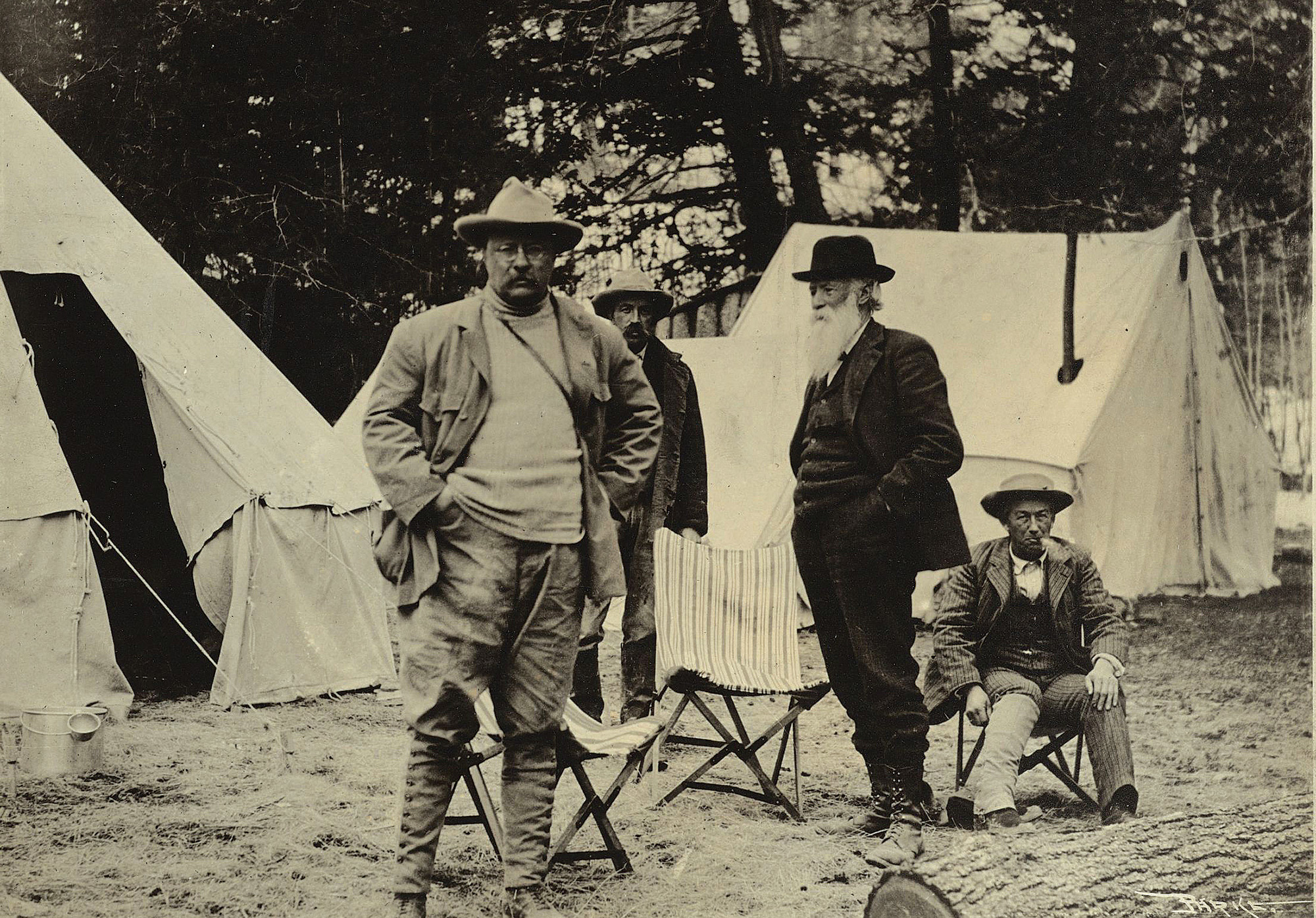

Roosevelt and naturalist/essayist John Burroughs spent hours perched on mountainsides counting elk, gleeful at the huge herds that had developed in the few short years since their near decimation. And Roosevelt, absent briefly from the desk-bound duties of a president, renewed his one-on-one relationship with the wild world. April snowdrifts still blocked some of the park’s wagon roads, so he took off on skis, often alone, on long jaunts without Secret Service interference, immersing himself in this terrain he so loved.

Roosevelt stayed true to his pledge that he wouldn’t kill any game within the park (newspapers had published an erroneous rumor that he’d be hunting in Yellowstone) with one exception: He killed and skinned an odd-looking mouse for return to Eastern experts under the hope that he had discovered a new species. (He had not.)

In this anniversary year of the National Park Service, it’s appropriate to reflect on a great man with a great vision. His accomplishments as the conservation president are legion: creation of the U.S. Forest Service, 150 national forests, 51 federal bird reserves, four national game preserves, five additional national parks, and 18 national monuments via the 1906 Antiquities Act. Those of us who still pursue, under the big sky, the game animals Theodore Roosevelt had so much to do with preserving, can take pride that the bulk of his conservation and hunting ethic developed in and close to Montana, on the back of a good horse with a saddle scabbard under his knee.

- Eighteen years later, President Roosevelt visited Gardiner and Yellowstone National Park as part of an eight-week, 25-state tour of the West. Photo courtesy of Library of Congress

- President Roosevelt spent 16 days in Yellowstone National Park, often in the company of conservationist and author John Burroughs (standing, second from right). | Photo courtesy of Theodore Roosevelt Collection, Harvard College Library

- On April 24, 1903, Roosevelt gave a speech honoring the dedication of Yellowstone Park’s arched gateway in Gardiner, Montana. | Photo courtesy of Theodore Roosevelt Collection, Harvard College Library

- A young Theodore Roosevelt with his beloved horse, Manitou, in 1885 on the Dakota prairie. | Photo courtesy of Theodore Roosevelt Collection. Harvard College Library

No Comments