25 Jul Images of the West: Arthur Rothstein in Butte

In 1936, a young photographer named Arthur Rothstein snapped a photo of a farmer in Cimarron County, Oklahoma, racing with his children to a ramshackle shed to escape a dust storm. That single snapshot framed the grim horror of the Dust Bowl with essential simplicity, and it became, justifiably, an iconic image of the desperation of ordinary Americans during the Great Depression, especially as felt by those on the Great Plains. Rothstein’s visual image is like a thumbnail trailer for The Grapes of Wrath, John Steinbeck’s Pulitzer Prize-winning novel that appeared three years later, and it established Rothstein as one of America’s premier photojournalists.

In fact, the year that The Grapes of Wrath appeared (1939), Rothstein traveled to Butte, Montana, where he took hundreds of photos of depression-era street scenes and panoramic views capturing Butte’s urban squalor and grimy skyline, resulting in a small catalogue of photographs that immortalized “The Richest Hill on Earth” as another corner of the American landscape that had been bumped and chipped in the economic crash, survival of which gave it a considerable measure of its enduring character.

Born in New York City in 1915, Rothstein graduated from Columbia University in 1934, where he had studied under Rexford Tugwell. One of Tugwell’s colleagues, Roy Stryker, in addition to being an economist, happened also to be a photographer, who sagely hired a whole corps of talented photographers to document the American heartland as it was ravaged by the twin vectors of the Dust Bowl and the Great Depression. Under the aegis of the Farm Security Administration (FSA), Stryker hired a platoon of photographers, starting with Rothstein, whose approach to documentary photography would set the standard for all the FSA photographers, and whose ranks would eventually swell to include such luminaries in the field as Dorothea Lange, Walker Evans, and Gordon Parks.

In his 1986 book, Documentary Photography, Rothstein noted that documentary photography, as it was inaugurated in the early 1860s by Matthew Brady, had immediately affected the political milieu, so much so, for example, that Abraham Lincoln admitted, “[Matthew] Brady and the Cooper Union speech made me President of the United States.” Rothstein’s own photographs became hard evidence confronting the policy makers in Washington, and at the same time gave the suffering a human, American face.

Rothstein’s way with words matched his finesse with the lens. He once condensed the essence of his art form with such brevity that he made it seem obvious: “The documentary photograph tells us something about our world and makes us think about people and their environment in a new way.”

But documentary photography possessed another, perhaps subliminal power: In its uncanny ability to immortalize tragedy as much as triumph, it could efface the dim barrier of memory and preserve the past as incontrovertible truth — a result that had powerful political consequences.

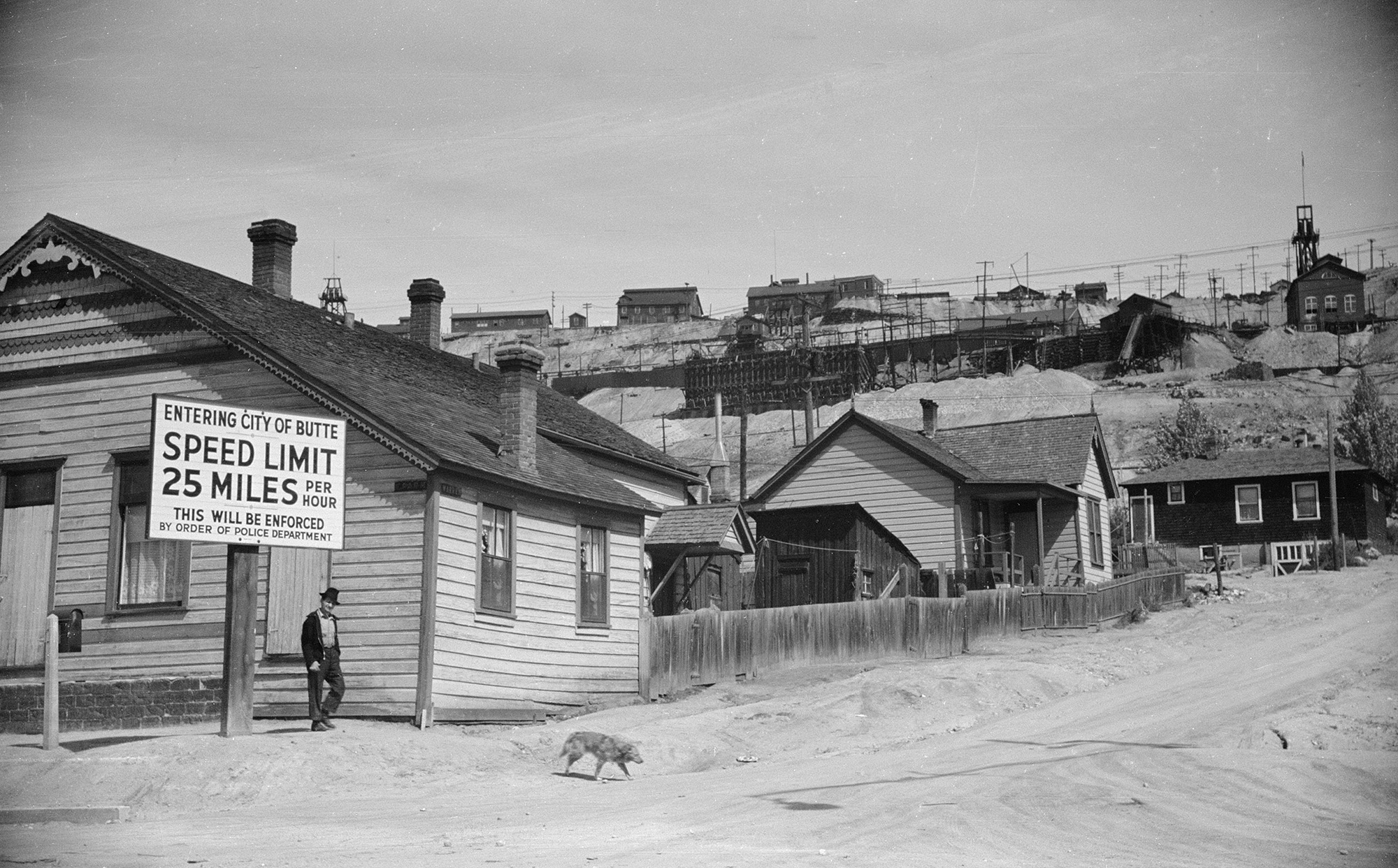

Rothstein’s “Entering Butte” (1939), for example, like many of his shots of Butte, captured a small section of a working class neighborhood that was representative of the town itself and its dearth of greenery, the plain homes of impoverished families having hardly been upgraded at all from the crude shacks of the earliest prospectors 80 years earlier. Rothstein remarked in his book that “[a]n important element of the documentary photograph is the fact that it usually needs words to make its image effective. Many documentary photographs include signs, graffiti, or billboards.”

In the case of this picture of Butte, the ominous warning of a strict police department juxtaposed with the unwelcoming aspect of streets of dirt and fences of unpainted wood and not so much as a single tree or blade of grass strikes a disturbing tone: Here the element of concern seems incongruous, if not pointless. After all, one ordinarily associates 25 miles-per-hour speed limits with healthy communities and manicured green lawns.

The tension between the ostentatious gingerbread adorning the gable, meanwhile, and the resourcefulness of simply nailing the street signs to the corner of the house marks another schizoid moment in the grim reality of Butte — not to mention the way the siding of the house is tucked right down into the dirt, where it’s beginning to visibly decay.

I’ve always loved the body language of the fellow caught in Rothstein’s frame here, too. He seems suspicious of anyone who would want to take a picture of this squalid corner of Butte, but he seems curious at the same time, and you get the sense that after the shutter snapped, the two of them — Rothstein and this unidentified denizen of East Butte — ended up swapping stories over boilermakers just down the street at the nearest bar, even if their conversation started with the man asking Rothstein just what the hell he thought he was doing.

Meaderville, captured in another of Rothstein’s historic photos, was home to Butte’s Italian population. The Rocky Mountain Café, pictured here, was owned by Teddy Traparish, known by locals as “Mr. Meaderville.” The restaurant gained a nationwide reputation, helped in part by rave reviews from writers and gourmands such as John Gunther, who in his 1947 Inside USA, immortalized the place:

In the suburb of Meaderville, is one of the best restaurants in the United States. Here, under the very shadow of the gallows frames and with the dollar slot machines making a splendid clink, coatless miners buy Lucullan meals. I don’t mean to sound ungracious, however. I will never forget Mr. Teddy Traparish and his Rocky Mountain Cafe. The steaks are seven inches thick, and cover half an acre.

Meaderville unfortunately succumbed to the encroaching maw of the Berkeley Pit in 1961, which merely increases the depth of gratitude we owe Rothstein for having taken his shots in Butte. The last remnant of the famous “Meaderville cuisine” lives on in Lydia’s Supper Club out on Harrison Avenue, thanks to a savvy Lydia Micheletti who moved her restaurant from Meaderville onto the flat in 1946. Like Rothstein’s photo, it preserves a vestige of one of the neighborhoods that contributed to Butte’s ethnic diversity and cosmopolitan mystique.

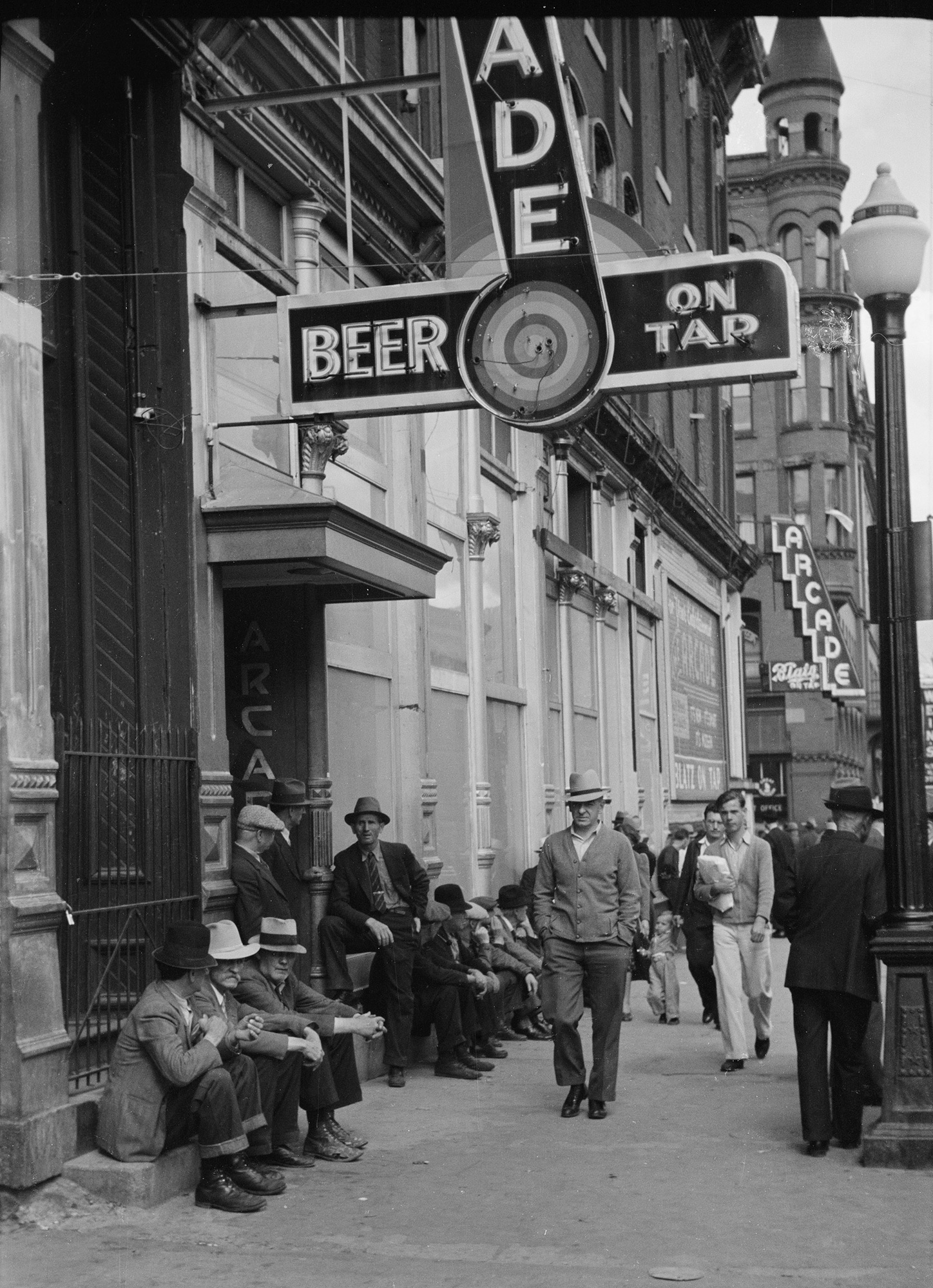

The corner of Park and Main in 1939 was the nexus of Butte’s uptown, an intersection swimming in neon and cigar smoke beneath the marquee of the famed Arcade Bar. The Arcade occupied a prime location on the northwest corner, just down the street from one of Butte’s most venerable and venerated establishments — the M&M Café.

The Depression hit Montana hard, especially Butte. The national unemployment rate in 1939 was 17 percent, but in Butte, one in four people were on relief. The men “lounging” on Butte’s busiest street corner were like men all over the United States still in the throes of the Great Depression. Such men gathered at street corners awaiting temporary hiring, or listening for snatches of promising scuttlebutt, or simply commiserating, the way men do: feigning mirth in the glow of a tavern sign, surrounded by the bustle of industry just out of reach. The men in Rothstein’s photo look surprisingly upbeat, displaying an equanimity characteristic of Butte folk even today, long after the mining that was its lifeblood for more than a century has gone the way of neighborhoods like Meaderville. Butte pride is in some ways a coping strategy for dealing with the general existential gloom that often hangs over the town like its scudding clouds of winter weather.

Rothstein’s photo of Butte’s infamous tenderloin — “Venus Alley” off of Mercury Street — nicely illustrates how documentary photography often exploits unplanned incongruity to make its point. By shooting the entryway to Butte’s brothels in broad daylight, Rothstein confronts the reality of the world’s oldest profession and its indelible presence on the Butte landscape. The unsubtle wording on the gate (“Men Under 21 Keep Out”) invokes the presence of the actual sex workers housed in their cribs just on the other side of the wall, women who were probably asleep when he took the photo. The harsh light on the nondescript entrance with nary a woman in sight underscores rather than eliminates the tawdry reality of Butte’s underside.

Rothstein’s images of Butte so artfully captured its raw essence that they have in turn contributed to the composition of its now world-famous persona. His pictures of Butte preserve glimpses of neighborhoods long gone, sacrificed to the insatiable maw of the Anaconda Company, and thus rescue elements of Butte that would be otherwise relegated to the faulty and quickly fading files of human memory.

Instead, one cannot wander the streets of uptown Butte without seeing the ghostly traces of the town as it was, so deftly captured in 1939 by young Arthur Rothstein.

- Gambling house, Butte, 1939

- Father and sons walking in the face of a dust storm. Cimarron County, Oklahoma | Photo courtesy of Library of Congress

- Men Lounging in Front of Arcade, Butte, 1939 | Photo courtesy of Library of Congress

- Main Street, Meaderville, Butte, 1939 | Photo courtesy of Library of Congress

- Entrance to Venus Alley, Butte, 1939 | Photo courtesy of Library of Congress

- Photo courtesy of Library of Congress

No Comments