28 Nov House Justified

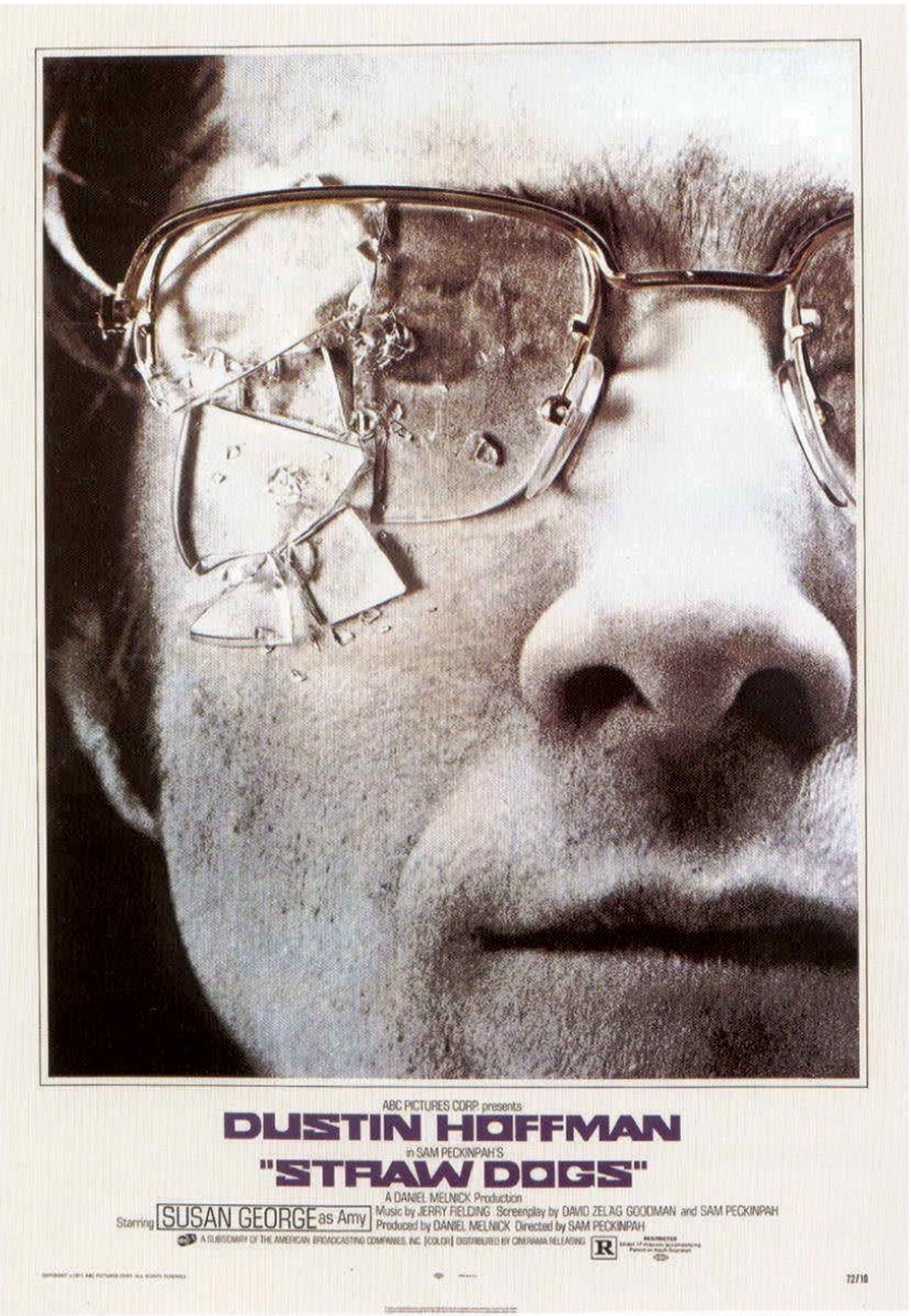

A HALF-DOZEN BULLET HOLES pockmarked the ceiling in Sam Peckinpah’s apartment at Livingston’s Murray Hotel, holes the director placed there one night while tossing in a fit of drug-fed paranoia. A Duncan Phyfe table 14 feet long stood near a rough-hewn bar where Peckinpah cheered pals such as actors Rip Torn and Warren Oates with strong drink and stand-up arm wrestling. To its left I remember a New Year’s Eve photo of himself and a man who appeared to be Henry Fonda – party fezzes askew and tinsel dripping – captioned “Story Conference.” Beyond was Western memorabilia: a potbellied stove, a windup Victrola scratching Spade Cooley foxtrots, and walls hung with posters from the director’s films: The Ballad of Cable Hogue, Straw Dogs. To the right was a shrine consisting of an antique Remington typewriter, upon which Peckinpah composed screenplays, framed by photos of himself directing, of his cowboy-bodyguard Allan Keller, and of cast members from Bring Me the Head of Alfredo Garcia. On a shelf was his leather-cased pool cue with the inscription, “To Sam Peckinpah, the world’s second-worst pool player,” a royalty check from MGM for 50 cents, sake cups, an Asian thermos, an autographed picture of Harry Truman, the director’s copy of Paul Seydor’s book, Peckinpah: The Western Films, and a wooden ranch sign reading, “Listo Para, Sam Peckinpah. Al Garcia.”

Peckinpah lived at the Murray from 1979 until 1984 – when he died in California of heart failure. He wrote as well as directed, so it was comforting that novelists Richard Brautigan, Thomas McGuane, and William Hjortsberg resided outside Livingston, as did the actors Peter Fonda, Jeff Bridges, and Margot Kidder. But it was Warren Oates (star of Garcia and a Wild Bunch outlaw) who brought Peckinpah to Montana. They purchased property together on Six Mile Creek near Emigrant in 1976. At Oates’ death in 1982, Peckinpah kept the cabin he’d built there – Dennis Quaid later owned it – but lived at the Murray as a recluse.

There he had offices for his Latigo Productions, slept, wrote, and indulged. During August 1980 and in October 1983, I lived one floor below him. He was rarely heard from, except for an occasional shot fired through the ceiling or a call downstairs to the bar. A sign on his door – THE OLD IGUANA SLEEPS, AND THE ANSWER IS NO – discouraged visitors. He appeared in public once that first summer. He bought into the Murray’s poker game, laid $1,000 on the barroom table, lost $700, picked up the remaining three, said, “Boys, you’ll never get this,” and ate it.

After Peckinpah’s death, I moved to his apartment. It consisted of five rooms, with a kitchen and two baths. I lived there during the summers of 1989 and 1990. Downstairs each morning a woman played “Home on the Range” on an oversized Hammond. At night trucks rumbled up Park Street, and saloon patrons who’d been dancing to the Murray’s jukebox since 11 a.m., might be gaga to a live band by eight. Bikers, bindlestiffs, and big game hunters could be seen in the lobby – such as those spied one afternoon, grimy with five days’ beard, who’d spread a six pack of Lucky Lager around two .30-.30s disassembled for cleaning. Sundays it was hard to tell whether Angelus bells summoning the faithful emanated from church or the depot across the way. While engines clanged in the railyard, music sifted from the bar and the Old Iguana’s boot heels beat time in memory.

When Peckinpah moved to Montana in 1977, both his reputation and his health were in decline. Convoy – the film version of C.W. McCall’s truckers’ ballad – had been completed, and though it would prove the highest-grossing picture of his career, it received terrible reviews. And delays due to his drug and alcohol use during its filming had resulted in his being blackballed by the industry.

He had grown up by the Sierra Nevadas – a mountain near his Fresno home was named Peckinpah – and his great-grandparents had been pioneers who migrated west. “They became lawyers and Judges,” he would say in a 1972 Playboy interview. “They got too respectable. But my granddad, Denver Church, had a 4,100 acre cattle ranch in the foothills of the Sierras … my earliest memory is of being strapped into a saddle when I was two for a ride up into the high country. We were always close to the mountains … we’d summer in them and some winters I ran trap lines in the snow.”

Livingston was a return to that mountain West. He lived first at its Yellowstone Motor Inn, then at the Guest House, and intermittently at Chico. “He loved Chico,” remembers Mike Art, the owner then. “And his stories were terrific. We cashed a lot of fun checks.” Then in 1978, Pat and Cliff Miller bought the Murray Hotel in town and began its restoration. Peckinpah moved his Latigo production company first into room 204, then to a large suite at the third floor’s rear, once leased by Walter Hill, son of James J. Hill of the Great Northern Railroad. Hill had decorated it with crystal chandeliers and ornate French doors, but Peckinpah covered its walls in barn siding and built a standup bar in its living room. He added a wood stove – “The heating wasn’t good back there,” Pat Miller says – and placed it on bricks above the pine floor. “He had a huge wood box and the living room was very cozy and interesting,” Miller wrote in her memoir, Life is What Happens to You When You Are Making Other Plans. “His floor-height sofa and chair had been on the set of Straw Dogs.” The sofa had been the one upon which the female lead had been so controversially raped.

Violence was one of Peckinpah’s cinematic themes, and he was known to be violent – toward family, friends, and lovers. Ex-wives attested to this, and Miller says, “He threatened his son, Matthew. He’d make him sleep in a bag outside the door. He didn’t want him inside with the drugs.” Livingston’s Joe Swindlehurst – who would remain Peckinpah’s friend and attorney throughout the Montana years – met him professionally. “He got into trouble with a young female film person. It was something that would have landed him in jail in 2016.”

Before the Straw Dogs sofa, Peckinpah built an entertainment center with a large TV and a screen for showing films. He decorated the walls with photographs, one-sheets, and Western prints by the artist John Doyle. Several of Peckinpah’s six Picassos were hung. For security he installed an alarm wired to the Livingston sheriff’s office, and protected his skylights with bars. In later years, drenched in paranoia, he would sit in the suite’s entranceway snorting cocaine, cradling a .44 magnum, and blasting through the door at imaginary assailants.

“The shots fired through the ceiling were like that,” says Miller. “That night he thought he saw demons. He may have had the DTs. When the roof leaked over his bed, he complained. I told him, ‘You shot through the roof, call a carpenter and get it fixed!”

Ten years earlier he’d been Hollywood’s darling, garnering reviews for The Wild Bunch, such as this from The New Republic: “Peckinpah is such a gifted director that I don’t see how one can keep from using the word ‘beautiful’ about his work. There is a kinetic beauty in the very violence that his film lives and revels in … The violence is the film.” And this from Time: “The Wild Bunch contains faults and mistakes, but its accomplishments are more than sufficient to confirm that Peckinpah, along with Stanley Kubrick and Arthur Penn, belongs to the best of the newer generation of American filmmakers.” He’d upped that ante with 1972’s The Getaway, then again with 1973’s Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid. But in 1979, he was lucky to find work as a second-unit director on other people’s films.

He took the jobs, though. “I’m a good whore,” he explained. “I go where I’m kicked.”

He’d had a heart attack in Livingston, one serious enough to require the insertion of a pacemaker. He spent two weeks at Livingston Memorial Hospital, recovering from the operation and from delirium tremens. Joe and Carolyn Swindlehurst picked him up the morning of his release. Doctor’s orders were no cigarettes and no alcohol. He’d been living at the Yellowstone Inn, and rather than go to his room, he turned into the bar. He ordered a Ramos Fizz, drank it, gurgled “Arghh,” and fell backward off the barstool. “We thought he’d died,” Joe recalls. “Carolyn started to cry and we’re looking at him. His mustache began to twitch. Suddenly he can’t help it anymore and he starts to laugh.”

“I just wanted to see whether you cared,” Peckinpah said.

That sort of humor endeared him to drinking buddies, but not to friends and family. By 1979, he’d gone through three marriages and was alone. Then he found the Murray.

The 1904 railroad hotel, enlarged in the 1920s, was straight off a Peckinpah storyboard. It was a fortress, like the El Paso hotel in The Getaway or the farmhouse in Straw Dogs. Its four stories, once elegant, had been gutted after the 1978 sale. A Murray investor and poker partner of Peckinpah’s told him about the Walter Hill suite. He took one look and booked it.

“He felt he’d come home,” Miller says. “He paid $700 a month and called me Boss Lady. There was never an edge to it.”

She wrote in her memoir, “We knew his health was very marginal. He walked downstairs. Someone always took him up in the elevator. I wanted him to run it himself but he declined with the excuse that he was not mechanical and if he got stuck between floors he would become suicidal. So we laughed and kept traveling in the 1905 Otis.”

Peckinpah, like many alcoholics, suffered from depression. He’d discovered cocaine on the set to 1975’s Killer Elite, where it was prevalent. It seemed the perfect intellectual stimulant. Freud had been addicted, as had the fictional Sherlock Holmes. Its deleterious effects then were not widely known. The drug cheered Peckinpah but intensified his paranoia, his personality shifts, and what may have been a bipolar disorder.

Fêtes in his suite became legendary; he was generous with his stash. “He’d make you snort it off the back of the toilet,” a friend recalls. “You’d straddle the bowl and suck it in with a straw.” The “loved him, hated him” dichotomy tilted toward “love” in Peck’s place. “He was really charming,” John Fryer remembers. “But he could turn on a dime.”

“I think he was split personality,” Miller says. The writer E. Jean Carroll, who interviewed him at the Murray in 1982, recalls, “There were several personality changes. He’d get in a mood and you’d get in a mood.” In her Rocky Mountain profile of Peckinpah, she describes chatting with McGuane, before which she noticed “the skin pulling around [Peckinpah’s] hairline … pulling and turning white around his cheekbones.” He slammed his fist on the table, cursed at the much larger McGuane, and invited him outside. No fight ensued, as “most of his violence was pure theatricality,” McGuane recalls. “But he was a terrible human being – depressed, angry, and with a serious drug problem.”

Despite Peckinpah’s abuse, friends stayed loyal and unsuspecting journalists fawned. His interviews were tremulously caustic. He chased a Japanese film crew downstairs at the Guest House, where the bartender had to restrain him. “He would blow up physically,” Swindlehurst explains. “But at heart he abhorred violence.”

Cocaine heightened his gunplay, which was not solely directed at humans. “Sam had a couple of cats in the apartment,” Miller says. “He wanted cats with no tails, so he tried to shoot their tails off. Shot along the edge of the floor. He didn’t hit any. But there were bullet holes in the entranceway.”

“He scared me with those pistols,” Mike Art recalls. “He’d wave them around. When he drank, he grew whiskey muscles.”

In addition to the .44, Peckinpah kept a Bible by his bed. “The pistol laid on top of it,” Miller says. “His Bible and his gun.” It was an image too loaded to have worked in his films, but it was redolent with the contradictions in his personality and of his past.

“My father was a superior court judge,” Peckinpah told one interviewer. “He believed in the Bible as literature, and in the law. He was an authority … a deeply religious man.” He also was violent, striking Peckinpah and his sister, Fern Lea, at any disobedience. His mother was a hysteric who bathed with him until he was 4 and slept with him each birthday night until he was 14.

“Mother, fortunately and unfortunately, was the most powerful figure in his life,” Fern Lea told Peckinpah’s biographer, David Weddle. “He got his creativity from her, though I’m certain he would have denied it. Sam was basically a woman, emotionally … I think he was embarrassed by it because in our family, ‘By God, the men are men!’ … he didn’t want that side of him to show.”

Inevitably it did, and the Peckinpah males were troubled by Sam’s delicate features and prettiness. Carroll recalls, “He was tiny. He could have played The Danish Girl.” His father “never understood Sam’s theatrical ambitions, his writing,” his sister-in-law Betty Peckinpah told Weddle. “For me, the tragedy of Sam was that he spent his life trying to find acceptance from that family. The macho posturing … that wasn’t Sam … It made him one of the saddest people I ever knew.”

The sadness manifested itself in uncontrollable rage and deep melancholy.

It persisted through military school, the Marine Corps, China during World War II, graduate school at the University of Southern California in drama, an apprenticeship in television, and from the first, a precocious directorial career. Drugs, alcohol, and women abated it, but nothing proved its cure.

“I saw him that way,” Miller recalls. “I felt really bad because he was alone and there wasn’t anybody in the apartment. One winter day he called and said, ‘Could one of the housekeepers come up? My kitchen’s so dirty and I don’t even have a broom.’ I sent up my mother. She cleaned his kitchen, then said, ‘He followed me around the whole time.’ She had been a nurse. ‘You know, Pat,’ she said, ‘he’s pretty depressed.’ He called me the next day and said, ‘What you doing Boss Lady? I thought you might get some whipped cream and raspberries and give me a back rub.’ I told him I’d take a rain check. He said, ‘You’ll take a rain check? Well, the offer will remain open.’ He was very lonely. There aren’t any raspberries in Montana in the winter.”

The one place from childhood where his spirits rose was at his grandfather’s ranch in the Sierras. “It offered a vision of paradise,” Weddle reported. “He watched the older men working the cattle in their leather boots and chaps and weathered Stetsons; smelled the wood smoke, sweat and dust … He drank in the rough, raw sensuousness of it all.” His grandfather had a rustic cabin “where a huge pot of beans, onions, potatoes, and venison was always bubbling.” At night, “he listened to the tales the men told … of cattle stampedes, desperate horseback rescues in mountain snowstorms, river crossings, prizefights and wrestling matches….” The stuff of his future films.

He would have his cabin up Six Mile. If not a replica, then a reminder of his childhood Eden.

There’s a scene at the opening of Ride the High Country, Peckinpah’s second film, that shows the view across Six Mile from his cabin. It is of a mountain framed by pines, evocative of the Sierras. When Peckinpah saw the high end of Oates’ property by the creek he must have recognized it. He’d situate his cabin there – which would prove not an easy process.

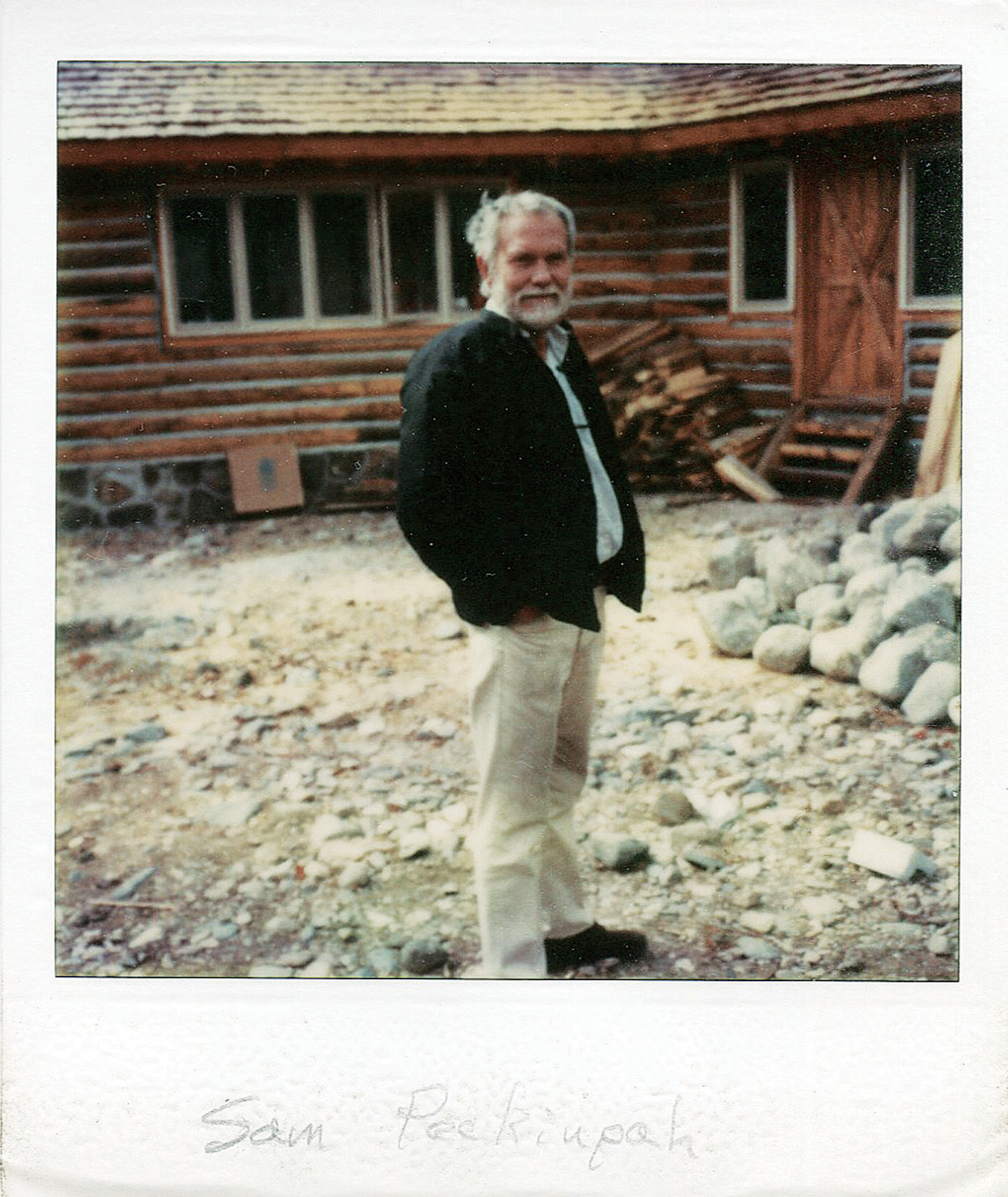

The contractor and tipi maker Don Ellis was standing in a field when he first heard Peckinpah’s name. “I was building a log house and this man – whom I’d seen drive by several times – stopped and said, ‘How’d you like to build a cabin for Sam Peckinpah?’ I said, ‘Who’s Sam Peckinpah?’”

The director had blueprints, so all Ellis had to do was haul timbers 4 miles up a winding dirt road, cut them on three sides and fit them to the architect’s plan. A Polaroid survives of Peckinpah smiling before the incomplete cabin. “He seemed happy enough,” Ellis remembers. “I built his kitchen counters, and the first time he saw them he stabbed a knife into one.” The cabin had a bedroom facing the lower Six Mile meadows, a stone fireplace and conversation pit, a small guest room, a dining area and kitchen facing the mountains. It was remote, had neither running water nor electricity, and “was a bear to take care of,” Ellis says. Peckinpah’s visits were sporadic. When there, he would drink with hangers-on like his bodyguard, the steer-roping champion Allen Keller; his neighbor on Six Mile, Harvey Counts (who’d done time for pistol whipping a man); and his attorney, Joe Swindlehurst. “He loved the cabin,” Swindlehurst says, “but after his heart attack he didn’t go up there as much. He was afraid something might happen.”

His emotional swings became wider and more frequent. Ellis recalls driving him through Yellowstone National Park to Cooke City, and on the way back “he started to hallucinate flying saucers. He wasn’t drunk, but you never knew what he might have taken.” He was writing a screenplay for a film about cannibalism on Donner Pass. It wasn’t going well. And the film projects he eventually accepted – second unit directing on the comedy Jinxed, and first unit on The Osterman Weekend – were beneath him or elegies to his paranoia.

Ellis was employed to hang barn siding on the walls of Peckinpah’s Murray suite, and built cabinets and the standup bar out of planks from a snow fence on the Millers’ ranch. While the cabin remained Edenic, the Murray suite – with its burglar alarms and grated windows, its hiding places for drugs and cash – became a paranoid’s bunker. “I used to check on him every afternoon,” Miller remembers. “He was nocturnal, so about one I’d go upstairs and call, ‘Sam?’ He would shout ‘Leave me alone,’ or ‘Get out of here,’ and

I’d know he was all right.” But some days the desk clerk Ralph White, would say, “Don’t go up there, Pat. He’s sitting in front of the door with a gun.”

Peckinpah had a brief marriage to Marcy Blueher (a woman Ellis later would wed) but his rages, the drug-fueled and alcoholic abuse, finished it. Then somehow he got better. “I always knew when he was trying to quit drinking,” Miller wrote. “An order would come … a case of club soda and a dozen limes would go up the suite. When I would see him later he would purse his lips in such a funny way and make faces at me.” But the last year of his life he remained sober. He made amends, shot two music videos for John Lennon’s son Julian, and contracted for a new film from a screenplay by Stephen King titled The Shotgunners.

Then he suffered a massive coronary and, on December 28, 1984, died. He was 59 years old.

“His lease for the suite had been up,” Miller remembers. “A few days before he passed he called and said, ‘Well Boss Lady, I just signed the lease for another five years. Will you be there?’ I said, I will be, unless you want to buy the hotel. He said, ‘Well, I’d love to buy it. If I could find the money, I’d buy it in a minute.’ He did love the Murray,” Miller says. “And to us, he was a friend.”

One summer day in the late 1980s, I hiked from Warren Oates’ former house near the mouth of Six Mile up the dirt road to Peckinpah’s cabin. His son, Mathew, was in the yard, and we sat staring at the mountains and chatting about his dad. What we said was inconsequential, but it was a moment. Mathew seemed to have settled with his father’s legacy. As he’d tell David Weddle, “It seemed like we really came to terms, in a lot of ways … He was trying hard not to be a crazy renegade, the wild son of a bitch that he’d been in the past. He’d call me up in the middle of the night sometimes and say, ‘You remember that time up in the cabin in Montana when I said so-and-so? I just want you to know I didn’t mean it.’”

Two lines from Peckinpah’s films came to mind. One, a quote from his father, that’s spoken by Joel McCrea in Ride the High Country: “All I want is to enter my house justified.” The other, written by Peckinpah, is from The Wild Bunch: “We all dream of being a child again. Even the worst of us – perhaps the worst most of all.”

I apologized to Mathew for having interrupted his privacy, and hiked back down the creek.

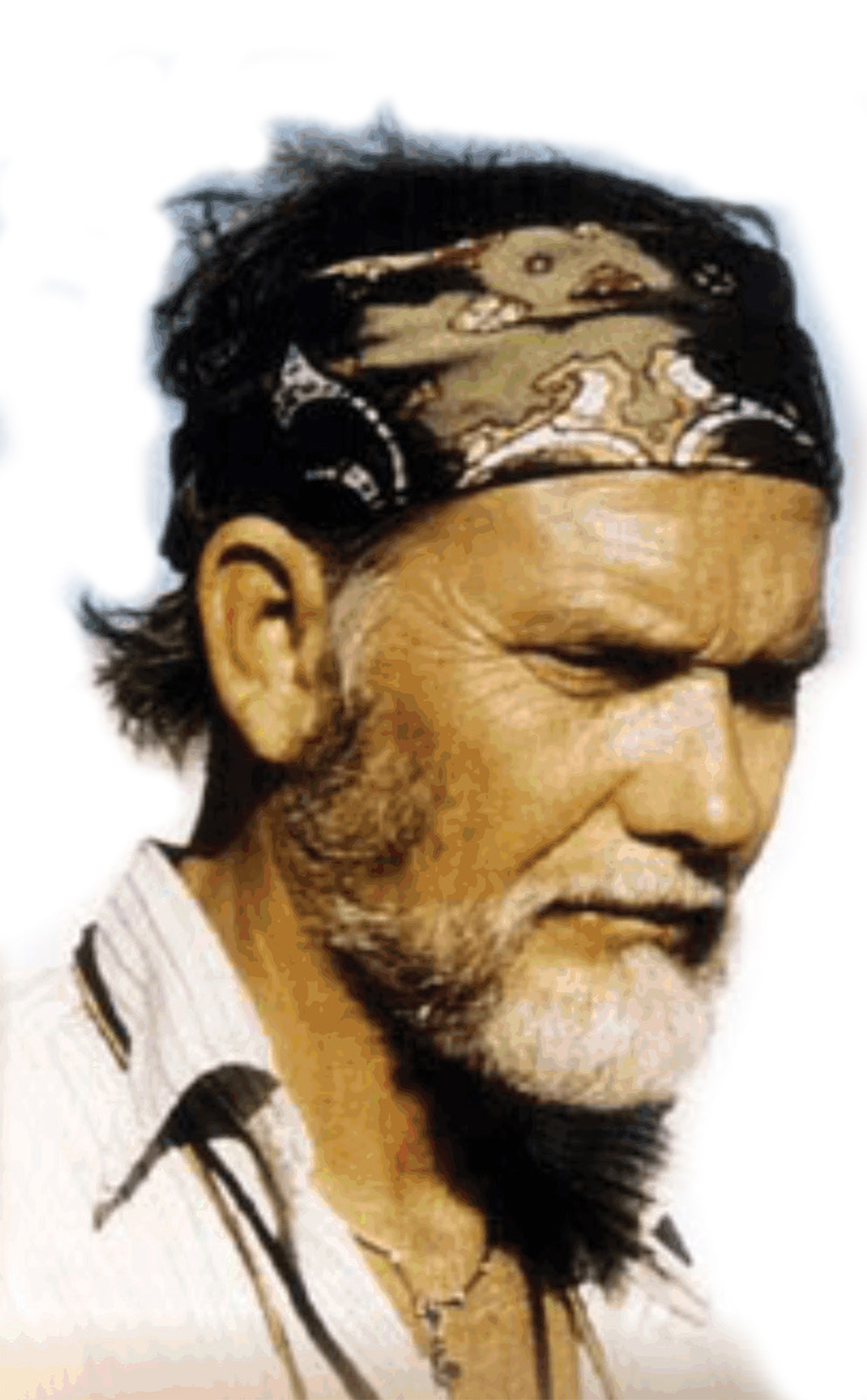

- During Sam Peckinpah’s admired, controversial, and often troubled career, he directed more than 15 feature films.

- During Peckinpah’s final years, the Murray Hotel in downtown Livingston, Montana, served as his residence and base of operations.

- Peckinpah’s cabin on Six Mile Creek south of Livingston was his retreat.

- During Sam Peckinpah’s admired, controversial, and often troubled career, he directed more than 15 feature films.

- Peckinpah’s cabin on Six Mile Creek in Montana’s Paradise Valley recalled aspects of his childhood. Photo by Don Ellis

- During Sam Peckinpah’s admired, controversial, and often troubled career, he directed more than 15 feature films.

Kate Axlund

Posted at 23:29h, 30 SeptemberOnce he fired at Matthew and hit the edge the of the bedroom door. Bearly missed him. I cooked once for Sam at the six mile cabin. Fresh elk liver. Had to try twice as when he’s said rare, he meant raw. Got it right the second round!

No one ever mentions “The Ballad of Cable Houge” when they mention his movies. I loved that one as well!