01 Jun History: Working the Lode

The antique mall below Last Chance Gulch in Helena, Montana is full of temptations. Myriad treasures fill the rooms, many beyond price. An enormous glass bowl full of colorful matchbooks draws my eye. Atop them lies a tattered brown book. About the size of a checkbook, it proves to be a pocket diary similar to those given away these days at local businesses. But this particular diary was printed in 1902. Though a few pages are missing and there’s a hole in the leather cover, its price — only $5 — proves irresistible. I pay for the diary and take it with me, thrilled at finding another uniquely shaped piece of the jigsaw puzzle that is Montana’s history.

On the cover, embossed in gold, are the words “Laird & Lee’s Diary and Time Saver.” The page that might have revealed the owner’s name is torn out. The book has a curve to it, perhaps due to time spent in a back pocket. Some pages have been used as scratch paper, and taxes for 1906 are jotted on another.

Around 1906, the Bureau of Agriculture, Labor, and Industry of the State of Montana reported that there were about 10,000 men engaged in mining in the Treasure State. The diarist appears to have been one of them: The most frequent notations in the book concern the locating of mines. “Locating” is a legal term for staking a claim. This became common during the California gold rush when 49ers drove stakes into the ground to mark areas they claimed.

For a mere $5, a tattered pocket diary returned a wealth of Montana mining history.

The Montana Bureau of Mines and Geology at Montana Technological University in Butte maintains thousands of Montana mining records and was a good starting place as I set out to uncover the diarist’s story. A reference in the diary to staking the “MagPie” and the “Blue Jay” seems to provide a clue, but no easy answers: The mines’ names aren’t unique.

I find more tantalizing hints on the worn, faded pages. One mine was located for “self,” while another was located for “CDM by W.T. Parkison.” The archives of the Montana Historical Society in Helena turn up the Parkison family in old city directories. Often, a pioneer family lost its connection to its descendants as succeeding generations Anglicized their names. With the Parkisons, it appears to be more a matter of bad spelling. One year they are referred to as “Parkinson” — the next, “Parkenson” — then they are dubbed “Parkison.” Across the references, first names, addresses, and occupations ensure that they are all the same family. During several years, W.T. is listed as a student at the Helena Business College, a bookkeeper for a publishing company, a mine superintendent, an assistant chemist, an assayer, and a miner.

It’s still not certain whether or not W.T. is the diarist, but his family is an interesting find. His father, W.H. Parkison, was a well-known Montana pioneer. Born in Pennsylvania in 1814, his memories include the nation’s grief at the deaths of Thomas Jefferson and John Adams in 1826. He came to Montana as a steamboat captain, and, in 1853, he brought a number of West Point graduates up the Missouri River to Fort Benton, then a trading post on the river, to survey the famous Mullen Road, which connects Fort Benton with Walla Walla, Washington.

The senior Parkison’s wife’s story was nearly lost due to latter-day misspellings. Even her obituary writers spelled her name “Parkinson.” As the teenage bride of a nearly 50-year-old adventurer, she had begun her 1864 wedding journey from Denver, Colorado to Virginia City, Montana in a fine carriage pulled by high-stepping thoroughbreds. The journey wasn’t easy. Though the carriage survived the trip, it was dragged into the rough mining community by a team of oxen.

With such colorful family connections, it’s tempting to conclude that the diary belonged to young Parkison, but wishful thinking isn’t proof so I continue my search. In handwriting neater than the diarist’s customary scrawl is “Mrs. Thos. Sullivan, No 562 Franklin St., Cambridge T, Cambridge Mass.” Another complete address is that of “Charles Couch, 19 Doane Street, Boston, Mass.” A letter to the Cambridge address elicits no response. A letter to Doane Street is returned to sender.

Charles Couch may have had mining interests. The Boston and Montana Consolidated Copper and Silver Mining Company operated in the Treasure State. Its superintendent was Thomas Couch. However, the most cursory examination of old census records shows that only some names were unique. Still, it’s another lead for me to follow.

“Following a lead” is one of many mining terms that have become common. A trip to Boston or Cambridge might provide some answers, but it would be a pretty expensive loss if it didn’t “pan out” — a mining term from gold-panning days.

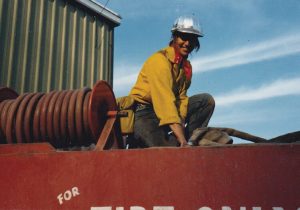

Unbeknownst to the author, she filled a water truck during the 1988 Combination Fire at a mine where the mystery diarist had worked 80 years earlier. Courtesy of Lyndel Meikle

Having checked the archives for the few names that appear in the diary, I seem to have hit a dead end. Nonetheless, there are other nuggets to be gleaned from the diary’s pages. Shopping lists occasionally appear. On more than one occasion, a bottle of “fluid” was purchased, at least once for someone other than the diarist. Could this have been — dare it be said — alcohol?

For years, the diary remains a mystery in my home, to be worked on occasionally between more mundane chores. The passage of time is a good thing. Archivists at the Montana Historical Society spent years digitizing their index to tens of thousands of historical documents. This means that, since my original record search in 2004, I can search the name “Parkison” by computer. The electronic search turns up some hits.

Viewing the actual papers from the Montana Historical Society still requires a trip to Helena. The archivist brings boxes of records up to the reading room. Finally, in the correspondence of Paul A. Fusz, I find a letter from W.T. Parkison. I open the old diary and turn its brittle pages with increasing hope. Then, as a miner might have said, “Eureka!” Parkison’s signatures in the letter and the diary are identical. As a bonus, I realize the mysterious “CDM” is likely to have been Parkison’s relative, Charles D. McLure, general manager of the Granite-BiMetallic Consolidated Mining Company.

During this search, I discover some interesting characters from Montana’s past. With W.T. Parkison identified, it is easy to follow his life by reading through old Montana papers, which document everything from social events with his family and his ownership of the Apex Mine near Virginia City to his untimely death in 1933 from a chemical explosion in an assay office of the giant Anaconda Copper Mining Company in Conda, Idaho.

Idle curiosity prompts me to search through libraries, biographies, newspapers, maps, and archives. Pioneers who had been “lost” by simple misspellings are found. One mystery is solved, but others remain: Who was Mrs. Sullivan? What sort of “fluid” was it? How did a 100-year-old diary find its way from a back pocket to a giant brandy snifter full of matchbooks?

Just when the vein appears to have played out, I strike another lead: A faded, penciled note on the inside cover of the diary reads, “Security Building, St. Louis.” Though not much of an address, could the reference point to a location like New York’s Empire State Building — so well-known that a street number was unnecessary?

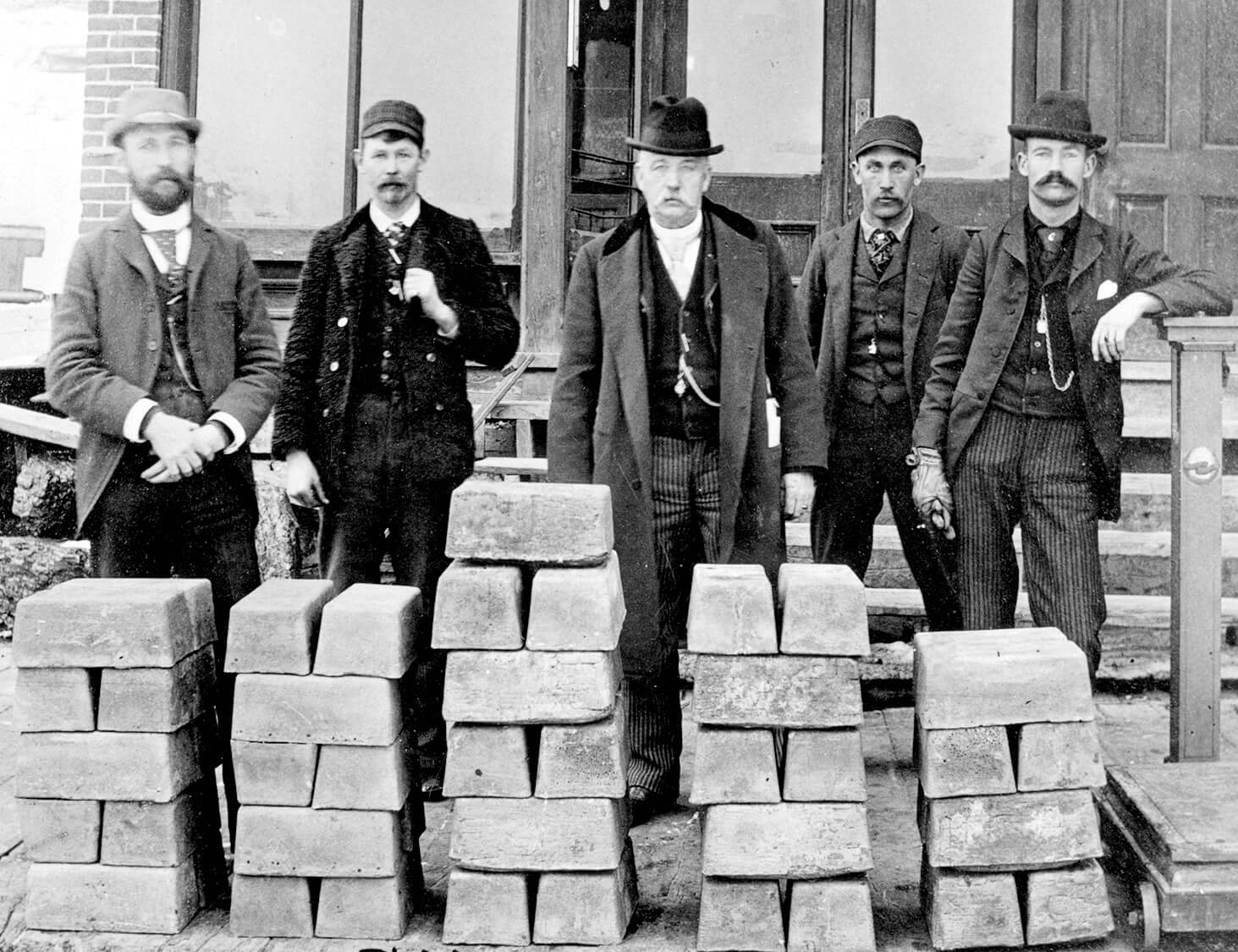

My hunch proves to be correct. The Security Building, which dates back to 1892, has been restored by the Lawrence Group, a small architectural firm that established its headquarters there. A call to the company, and a more than helpful discussion with David Ohlemeyer, reveals that during the building’s restoration, the company found a box in the basement containing old photos of Montana miners. As it turns out, Granite-BiMetallic once had its offices in the Security Building. Photos of the smelter and company officers were preserved in the box. My discoveries swing back and forth through Montana’s history like the pendulum on an antique clock.

In 1988, 16 years before acquiring the diary, I worked for the U.S. Forest Service on the Combination Fire near Philipsburg, Montana. Coincidentally, the Combination and Black Pine mines had been holdings of C.D. McLure. While I was filling a tanker with water at the Black Pine Mine, I asked mine employees if I could take a colorful rock from the tailings. They laughed and proclaimed, “Take them all!”

Ironically, 80 years before, W.T. Parkison had worked at the same mine. As it were, history is where you find it.

Lyndel Meikle was born in Helena, Montana. After serving as a flight attendant on troop transports for the Flying Tigers during the Vietnam War, she found a peaceful refuge in Yosemite National Park. A national park ranger since 1973, she finished that 43-year career at Grant-Kohrs Ranch National Historic Site in Deer Lodge, Montana.

No Comments