24 Nov History: Keeping Chinese Culture Alive on the Frontier

Every year since 1993, Butte has held Montana’s “shortest, loudest, coldest” parade for the Lunar New Year to celebrate the city’s historic Chinese community. Butte was once home to one of the largest Chinatowns in the Rocky Mountain region. The parade passes sites that once featured thriving gardens, restaurants, gambling halls, laundries, and religious temples, though few brick-and-mortar remnants persist today.

The institutions that remain in town work hard to honor the experiences of Chinese Montanans. Pekin Noodle Parlor, considered the longest continuously operating Chinese restaurant in America, links the present with the past through recipes that stretch back more than 100 years. The Mai Wah Society, which sponsors the New Year parade, includes a restored Chinese mercantile, noodle parlor, and museum. By hosting the parade, the Mai Wah Society and those who take part connect to the traditions of Chinese Montanans who worked hard to make a life under the Big Sky.

The Pekin Noodle Parlor is the longest continuously operating Chinese restaurant in the United States. Courtesy of CREATIVE COMMONS

Chinese migrants first arrived in Montana in the early 1860s, along with other settlers drawn by the prospects of wealth in mining. Montana’s Chinese population reached its height at more than 2,500 in 1890. They worked as miners and merchants, built the railroads, and started businesses. However, from the late-19th through the mid-20th centuries, American laws restricted Chinese migrants’ livelihoods, marriage prospects, and ability to become citizens. Due to racial animosity, Chinese communities faced boycotts, destruction of property, and the ever-present threat of mob violence. They were often described in newspapers with vulgar language and racist remarks. Yet, Chinese Montanans persevered and made a life in the region. They celebrated their traditions and holidays, asserting their commitment to keep their culture alive in a land far from home.

The annual celebration of Chinese New Year is an important event, providing solidarity, comfort, and societal continuity. Observed by many Asian cultures, this holiday falls between late January and mid-February, depending on the lunar cycle. Also known as Spring Festival or Lunar New Year, it is the most important holiday of the year, with traditions including feasting, gift giving, debt repayment, family reunions, and tidings of hope. Sociologist Rose Hum Lee, born in Butte in 1904, noted in her study of the religious practices of Chinatowns in the Rocky Mountain region that, “The festival of foremost importance is New Year. … Preparations begin during the late summer, when orders for delicacies and decorations are dispatched to China and to San Francisco wholesalers. Huge boxes of foodstuffs, firecrackers, religious and festive decorations arrive during the fall.”

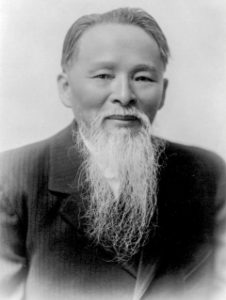

Dr. Huie Pock was a prominent and well-respected Chinese doctor in Butte, where his herbal medicine and acupuncture practice provided treatment for Chinese and Euro-American patients alike. COURTESY OF MAI WAH SOCIETY

In 1895, a reporter for the Anaconda Standard wrote about the importance of the holiday for Chinese Montanans, describing the celebration as the “Fourth of July, Thanksgiving, Christmas, and New Year all in one week instead of distributing them about the year.” While the comparison is apt, the reporter did not communicate that Chinese Montanans, so far from loved ones, felt tremendous longing during these observances at not being able to reunite with family, a key tradition during the New Year celebrations. Instead, Chinese Montanans — whether in Chinatowns with hundreds of residents such as those in Butte or Helena, or in tiny communities across the central and eastern part of Montana — adapted to conditions in the American West and kept alive the traditions that provided strength, enjoyment, and cultural connectedness.

While many Chinese Montanans celebrated the Chinese New Year where they resided, some occasionally traveled to larger population centers. A reporter in the small mining community of Neihart noted in 1899 that Tom Gong and Lee Gee traveled nearly 250 miles to be with friends during this most important of cultural traditions.

Other larger population centers across Montana also celebrated. A 1903 report from Butte recounts:

If you go down into Chinatown tomorrow, you will see the usual sights and hear the customary sounds attendant upon the great Chinese festival day. You will see the red papers pasted over the doors … the big Chinese lantern hung to the windows, newly burnished up; the crowds of idle Chinese bent on merry-making hanging around the stores and gaming places; the firecracker, paper-strewn streets, and all the rest of it.

A participant from Butte’s Chinatown noted the proper ritual observance:

Devout worshippers seeking prosperity for their businesses and families in China, visit the Temple and make personal offerings. The altar table before Kwan Ti [Guan Di] is laden with wine, roasted melon seeds, tangerines, oranges, chicken, bowls of rice, and slabs of cooked and roasted pork. The worshippers are dressed in their newest attire.

A report from the Whitefish Pilot commented on the festivities from the Chinese community in that town, numbering around 30. The 1908 report captures many of the elements of the celebration, emphasizing feasts and fireworks:

Visitors in Chinatown during this season are treated to various kinds of presents that come from their native land, such as nuts, candy, Chinese drinks, and other things. A leading feature in the celebration is the shooting off of fireworks, which are used in large quantities. Tom Quong, who is the leading Chinese shopkeeper in Whitefish, has been holding the front rank for hospitality since the first of the month, and everybody who has visited his place has been treated to some reminder of the occasion.

This altar from Butte’s Chinese Temple features a statue of Guan Di. COURTESY OF BUTTE-SILVER BOW PUBLIC ARCHIVES

For many Chinese Montanans, the New Year festivities became a way of building fellowship and goodwill across the larger community. During the first two decades of the 1900s, Bozeman restaurateur Chin Ah Ban frequently invited “city officials and prominent business men and women” to dine with him for New Year’s feasts. Guests included mayors, attorneys, bankers, business leaders, and more. Chin shared Chinese cuisine with the guests, who commented they “had never partaken of the Chinese dishes before them, but found them delightful.”

The type of guests featured at Chin’s feasts were similar to the dignitaries who enjoyed Butte resident Dr. Huie Pock’s hospitality at a large New Year celebration in 1896. The local newspaper reported that:

Dr. Huie Pock … gave a very elaborate dinner in honor of their New Year to a number of American friends last night. … The menu consisted of 13 courses, with different brands of imported Chinese wines and liquors with each, as follows: Bird’s Nest Soup; Bird’s Nest and Chicken Fricasee; Fish Fins with Minced Ham and Chicken; En Ka Va and Liquorine; Rice a la Chinese; Imported Chinese Pork, Cooked a la Pekin, with Coffee Sauce; Macaroni and Chinese Dried Oysters; Chicken, seasoned with Dates and Chestnuts a la Hong Kong; Dried Abalone, seasoned with Corean Dates; Jelly Fish seasoned with Lily Root and Mushrooms a la Wah Hai Wai; Stewed Octopus and Dried Star Fish with Haw Rinds a la Kong Suie; Imported Chinese Oranges; Liquor Extract of Lily Root.

During a period when Chinese temples suffered vandalism, arson, robbery, and destruction of important religious artifacts, Chinese Montanans maintained traditions despite the reality that openly practicing their spiritual beliefs could bring harm. They found strength and solidarity in a land far from home through the continuation of cultural practices.

Mark T. Johnson is a professor with the University of Notre Dame. His research focuses on the history of Chinese communities in Montana, detailed in his book The Middle Kingdom Under the Big Sky: A History of the Chinese Experience in Montana (2022). Raised in Great Falls, he now lives in Helena.

Douglas G Kaufman

Posted at 17:34h, 03 JanuaryWow that story is both heartbreaking and uplifting! Thanks for telling the story of these wonderful hardworking citizens of the Treasure State who did so much for all and without much deserved praise!