20 Aug Outside: Guilt by Association

Each spring in the mid-1990s my dad and I traveled to the Florida Keys and hung out with a business associate who considered public water, even if five boats were anchored on a single tarpon flat, to be his domain. As fists shook and obscenities spewed, he’d shout, “Those are our fish, too!”

Once, the businessman, who I’ll call “the Conch,” gunned our boat between a sexy flats skiff and a pack of happy tarpon, then cut the throttle as those fish approached. I kept my back to the anglers and didn’t launch a single cast as those fish swam past, mutiny from the Lilly Pad’s prow. It wouldn’t have been so bad if the Lilly Pad wasn’t so ubiquitous — she measured 28-feet from bow to stern, carried a V-hull and her flying bridge threatened low-flying aircraft. She was as inconspicuous on the shallow flats as the Nimitz might be on your local trout stream.

To make matters worse, each time we passed some staked-out dudes, the Conch, who wore ratty shorts, high-top hoop shoes, sleeveless T-shirts and a ball cap with the bill turned back, would shout, “What! Are you going on an African safari?” These were guys who paid $700 for a day on the water with a guide and an equal amount on the latest khaki fly-fishing fashion.

The day after my protest I was driving up the Keys highway in a built Jeep with a guide friend. For entertainment I said, “Hey Brucey, have you seen those jokers in that boat with the flying bridge?”

The guide sprouted a perplexed look and spat, “Oh my gosh, yes! That guy poached a pod of tarpon from Jim Teeny and me last night. He’s either going to get shot or he’s going to find his boat on the bottom of the Atlantic. People are talking about this.”

I don’t know what, exactly, I expected from those first trips to the Keys. Certainly, it wasn’t a full-on assault of the established guide community. And it wasn’t a big-time fish-fest, either. If a single tarpon, permit or bonefish arrived at the boat I’d be a happy man. If we strictly fished for dorado or sailfish, pulling plugs and skirts in the Gulf Stream, that was cool, too. More than anything, I wanted to visit the Keys and take in the sights and sounds, to confront my Hemingway fascination, and to drink beers in Key West and smoke cigars outside in shorts, bare-chested at midnight. It seemed like something aspiring novelists should do.

The first year I went to the Keys, the fishing, and everything else for that matter, exceeded expectation, mostly because there wasn’t any expectation — I hadn’t studied tarpon or even prepared adequately to fish for them. I didn’t even know if we’d fish and, if so, which species we might pursue. We didn’t even know if the Conch owned a boat. Three hours into our trip there was no way to lose; Dad and I were flying first class to Marathon, gratis. In that drumming haze at 30,000 feet, somewhere over Kansas, I assume, and just after I said, “Yes, yes, I believe I will have another Cutty Sark,” I felt like a young life was being lived to its fullest and prospects seemed infinite — fresh, unknown land ahead, laced with tropical weather and warm Caribbean water.

It turned out that the Conch did own a boat, the aforementioned Lilly Pad, and we were tooling out of a channel on the Atlantic side of the Keys, just two hours after our flight touched down in Marathon.

My dad and the Conch rode high in the flying bridge, I scanned flats from the stern. Perhaps 15 minutes passed before I said, “What are those?” and pointed to the left. The Conch shouted, “Tarpon!” and cut the throttle. I loaded line and cast a green cockroach. Ten minutes later I brought a merciful 50- or 60-pound tarpon into the boat. Twenty minutes after that I hooked a small permit. Later, I hooked a big, migratory tarpon weighing at least 100 pounds. My 8-weight threatened to snap and I vowed to arrive the following year with saltwater wisdom and nothing less substantial than a meat stick in tow. That, I understand now, was the beginning of the end.

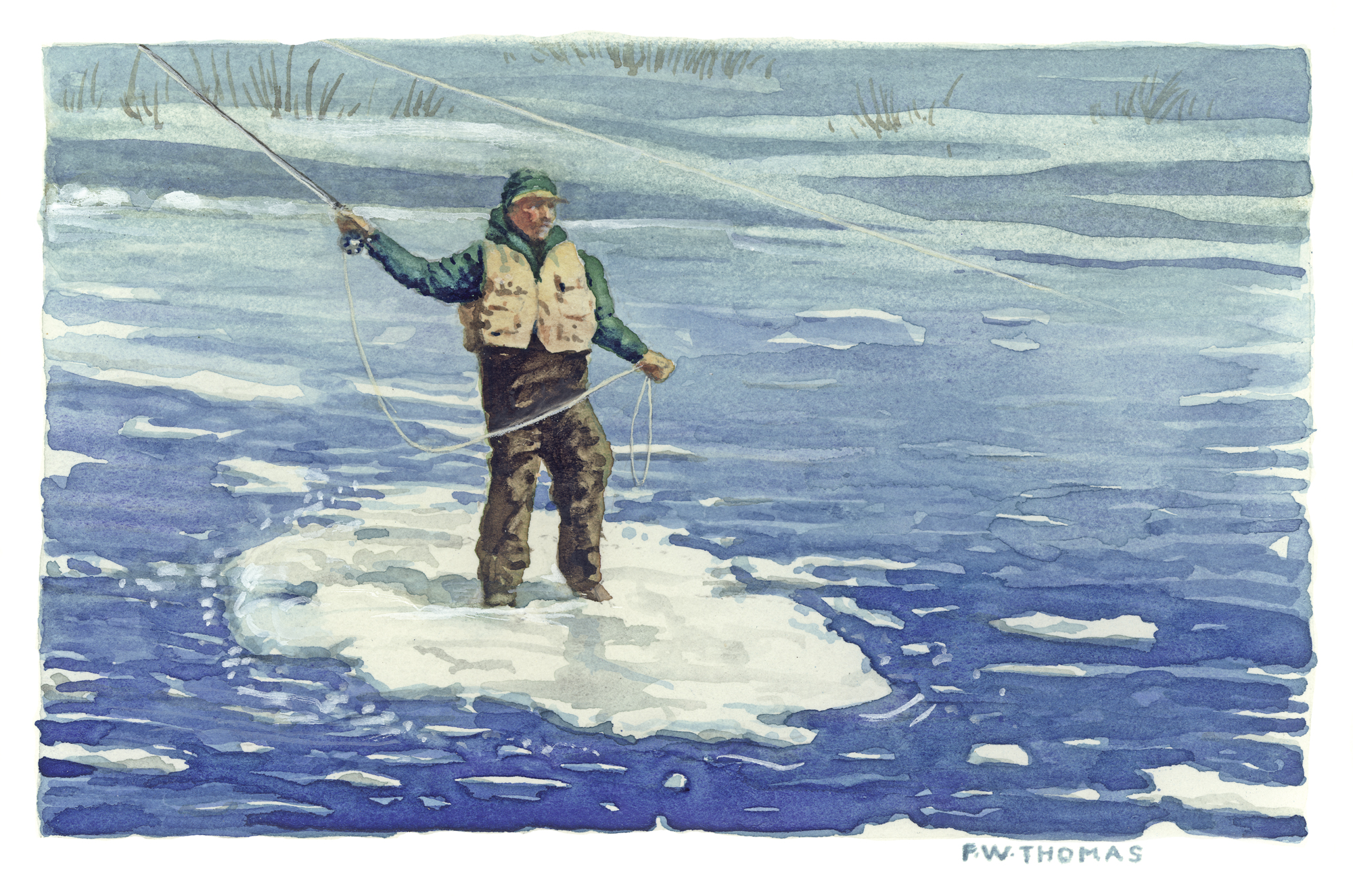

The next year dad and I arrived in Marathon with all sorts of expectation. I read every book on tarpon I could find, including John Cole’s underrated gem, Tarpon Quest, which I consider the most honest literary depiction of tarpon fishing. I spoke with longtime tarpon guides and milked them for advice. They supplied proven flies and constructed Bimini twists, a far cry from the blood knots and improved cinches I’d used the year prior. This time I wanted to be Tarpon Man, not some trout hack from the Rockies who was more interested in cigars, coffee shops and Duval Street than a fish on the end of his line. I had something to prove and my attire, those khaki safari clothes, placed me as a flats angler, much to the Conch’s disgust.

The Conch, more successful than ever, arranged for delivery of a new boat, a 40-foot cigar-shaped powerhouse with twin 250 Yamahas attached to its stern. If the Lilly Pad was conspicuous, the new ride was downright colossal. Brought down on a calm weekend from New Jersey, clipping along at 70 miles an hour, it arrived with some Mafiosos at the helm and a surgically enhanced babe on its bow. Its cargo space — i.e. the cooler — was littered with Heineken beer. The Conch invited my father aboard and told me to stay behind. As they pushed away from the bulkhead I glanced from the silicone squeeze to my dad and realized the feelings he must have had when I was in high school requesting keys and speeding away on Friday nights with friends.

Fortunately, my father survived all that theater and the next day we were fishing dorado 20 miles off the coast, directly in the shipping lane. As a tanker bore down, Dad and I exchanged nervous glances, but nothing now seemed shocking. I can say this: You’ll never know how truly large and fast oil tankers are until you reside directly under one’s bow while your oblivious skipper winds monofilament around a flying fish. As the horn blasted, the Conch hit the throttle and we sped out of the way, then turned the nose of that boat toward Cuba. For once, I saw purpose in those twin 250s.

That afternoon, on an endless ocean, the Conch cut across the bow of a rickety fishing boat and the circus continued. By now we were closer to Havana than Key West and that boat turned into our wake. As the Conch shook fists, that foreign boat clipped our marlin skirts with its propeller. When the instigator asked, “Why’d he do that?” I answered, “Because he decided not to shoot us.”

Flying back to Seattle that year I looked like a whipped puppy with broad eyes, bad posture and a chin nearly dragging on the ground. Which placed me among the ranks of spoiled anglers who consider a trip of merit only if the fish feel frisky. It’s not all our faults. Writers ranging from Zane to McGuane set us up for these disasters, focusing mostly on willing combatants, rendering success only possible through personal angling glory.

I’d chased tarpon for two weeks, jumped a few and landed none. As the plane touched down in Seattle I held an equal amount of disdain for scribes and those film editors who clip two weeks of footage into a power-packed half-hour TV show, sufficiently bolstering anglers’ expectations beyond reason. I admit that my life revolves around fish and fishing and during times of trial I rank with the worst, able to blame just about anything, except myself, for a dismal catch rate. If the Conch was to blame I was an equal influence in the final score, my casting having dissolved to infantile when pods of 100-pounders swam by. And when I hooked a good fish I applied too much pressure and pulled a hook free or babied it into oblivion. There was a fine line between knowing too little and caring too much and I’d probably crossed the boundary on each side.

Year three provided equal fireworks, literally, as one day the Conch found a piece of flotsam in the Gulf Stream and considered options for the fish that finned underneath. First he cast lures at a few tripletails. Then he reached into a gear bag, pulled out a quarter-stick of dynamite and, just as two other sportboats arrived on the scene, lit the fuse and let fly. I remember the concussion not being as loud as I expected. Nonetheless, three tripletails and a small dorado lay shocked on the surface. We scooped them up and roared away. That’s when I understood that expectation and circumstance, rather than place, direct the outcome of a fishing trip.

Despite my occasional disgust for the Conch’s etiquette, there was also something uplifting in his attitude, a carefree, like-it-or-else mentality that I’ve only occasionally grasped, and only for brief periods, in my life. Yes, we may have taken a bite out of some other fishermen’s days, but we also sped away from Florida with the most outlandish stories to tell, and my father and I were witness to another way of life, an attitude and ethic far different from ours, a perspective, good or bad, that would cement our resolve or change us completely. For the aspiring novelist this was a point missed during a bout of tarpon tunnel vision.

A couple days after the dynamite episode, the Conch flew back to Michigan, graciously leaving us with a skiff and the house — for three weeks we’d fish tarpon the way we wanted to, staked out or cruising the flats, adhering to unwritten rules, waving to the safari guys instead of raising a finger at them.

Unfortunately, perfection was a ghost. After three days on the flats I had that old, familiar feeling — entitlement and anger in the face of blind fortune. And there was another feeling, too, this one centered deep in my gut. My dad says he knew the problem was serious when I stepped off the bow, sat in the bottom of the boat and said, “Tell me when you see something.”

That night, nearly two weeks after the pain began, I landed in the emergency room at Fisherman’s Hospital, a burst appendix having turned toxic. As nurses wheeled me into the ER, and as my dad implored, “Don’t leave us,” I thought back to that moment when the Mafiosos took my father for ransom and he floated away on a Heineken breeze.

A month later I was back in Seattle, 30 pounds lighter than when I left. That portion of my Florida life was over, my own tarpon quest having lived up to Cole’s and exceeded it in some ways. In truth, there were a few tarpon conquests I’ve overlooked here. The point is, what’s memorable and pertinent has little to do with those tarpon and is fixed instead on the periphery.

Including this: One early evening, with the Lilly Pad anchored near several bomb craters, the Conch looped some line around a bent beer can, attached a live pinfish underneath, and cast that offering over dark water. That can bobbed in the chop for five minutes, then ducked under and the Conch immediately set the hook. A grand tarpon swirled on the surface, ran 20 yards then leaped in the air.

“You see,” the Conch shouted after taking a swig off another Corona, “We don’t need all those safari clothes to catch fish. We don’t need no stinkin’ guide.” With a toothy grin he concluded, “This is easy!” As we clipped away from the anchor and bounced through the chop, our flying bridge heaving to, our shouts melting on a broad ocean and a building wind, I found the answer to the traveling angler’s quandary: Expect nothing and you can’t lose.

No Comments