02 Jun Guardian of the Grizzlies

By most empirical measures, Doug Peacock is an undisputed winner. America’s most visible and vocal defender of grizzly bears, he has won battles over land management and prevailed in skirmishes over the fate of individual bears. His guerilla tactics have inspired environmental activists around the world, and he’s achieved two outcomes he could scarcely have imagined as a young insurgent: We have more grizzlies in more places than any time in the last century, and Peacock himself has grown old.

Peacock considers his role as an insurgent conservationist.

But Peacock, who splits his time between Montana’s Paradise Valley and the Sonoran borderlands of southern Arizona, doesn’t particularly feel like a victor. His long view of the fate of his totemic species — North America’s great brown and white bears — is that it depends less on conflict than its opposite expression: tolerance.

Whether we extend clemency to bears or persecute them as disruptive predators will determine the near-term fate of grizzly bears, especially those that roam the Yellowstone Plateau of Wyoming, Montana, and Idaho. Yellowstone National Park bears have been classified as a federally endangered species since 1975, but last December, the governors of the three states petitioned the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service to remove protections and allow states to manage them as trophy game animals, which would include sport hunting. Advocates for delisting grizzlies point to population estimates that suggest a recent record number of bears in and around the park.

The bookshelf in his study is dedicated to objects with personal histories — natural and otherwise.

But Peacock, who first encountered Yellowstone’s griz in the early 1970s — as he sought his own refuge in the park’s backcountry from trauma earned as a Vietnam War medic — says focusing on numeric benchmarks misses the point of recovery. “Classically trained Western wildlife biologists have trouble wrapping their heads around any other concept, but the counting-mallards and counting-deer theory of game management just don’t apply anymore, and especially to the griz,” says Peacock. “We’re dealing with forces that are beyond our comprehension, let alone our control.”

He’s talking about the searing impacts of climate change, which Peacock thinks will undo all the incremental habitat work that’s been completed over the last several human — and grizzly — generations. This includes unstoppable wildfires, the unrecoverable loss of obligate species, such as high-country whitebark pine and cutthroat trout, and low-country drought that pushes deer, cows, and humans into grizzly country. “You can’t simply raise a certain number of bears and say the bears are doing fine,” says Peacock. “Bears are not going to be able to stay in those protected places, because they will become less protected as habitat changes. So, if you want to talk about recovery, you’re going to have to talk about letting bears move to new habitats.”

This is where human tolerance makes all the difference.

When he’s feeling hopeful, Peacock indulges in a very specific dream. It starts with a wildlife- friendly underpass or overpass on Interstate 90, between Livingston and Big Timber, that allows wandering grizzlies to move north from the Gallatin and Absaroka ranges into the Crazy Mountains. From there, they would be free to move into the Little Belt and Big Snowy ranges, where they might mingle with their estranged cousins, eastward outcasts from the Bob Marshall Wilderness and Glacier National Park.

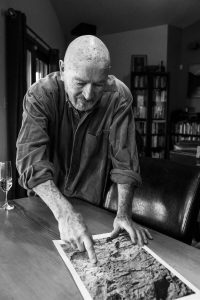

Peacock points out migration corridors on a map of the Yellowstone Plateau.

This genetically mingled population of grizzlies could, with human tolerance, then repopulate the river corridors of eastern Montana, including the lower Yellowstone and Missouri. That, Peacock says, is a durable definition of grizzly bear recovery, letting the great bears reoccupy the habitats where they were first documented by Lewis and Clark and other early explorers of the Northern Plains. Indeed, it may be the only way grizzlies — along with fellow high country travelers like wolverines, mountain goats, and wild sheep — survive the loss of alpine habitat throughout the Rockies.

Grizzly bears move across an open slope in the Northern Rockies.

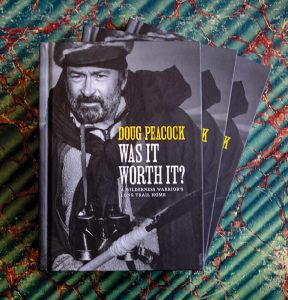

All these reconsiderations of bear survival — and a lifetime of dogfighting for grizzlies — are recounted in Peacock’s latest book Was It Worth It?: A Wilderness Warrior’s Long Trail Home. Published earlier this year by Patagonia, it borrows its title from an inscription Peacock found in the remote desert of southern Arizona during one of his many solo treks. Etched on a boulder near a hidden water source many miles from any road or town was the enigmatic scrawl, along with the date 1909: “Was it worth it?”

An Uneasy Evangelist

Native Americans enumerated significant events of the previous year by recording them on the tanned hide of a lodge. These were called the winter counts, and you can read Peacock’s book as his own winter count, taking stock of a lifetime of paying attention to nature’s sentinels. These include documenting declines in coastal salmon and steelhead runs, witnessing the erosion of the great forests of the Russian Far East and Amazon basin, chronicling the last Mexican grizzlies, and tracking man-eating tigers through India.

Peacock never intended to carry the expectations of a constituency on his broad shoulders (it’s not lost on many observers that he looks a little like a bear himself). He was, he admits, selfish in his pursuits and exclusive in his company. One of Edward Abbey’s original monkey-wrenchers and the model for Abbey’s charmingly anarchist character Hayduke, Peacock later found adventurous fellowship in the likes of Patagonia founder Yvon Chouinard, The North Face founder Douglas Tompkins, and television journalist Tom Brokaw.

With his companions or alone, Peacock explored the wild side of wherever he was, which, often as not, were the unexplored canyons of the American Southwest, forests of eastern Asia, or unmapped peaks from Chile to arctic Canada’s Beaufort Sea. The journeys have been unified by his interest in the welfare of apex predators, which have been pushed into our last scraps of wildlands. “I never intended to have a life so intertwined with griz,” says Peacock, who calls his first encounters with the species in Yellowstone a “pleasant accident” that rewired his mind. “Those bears redirected my life and gave me a purpose when I really didn’t have options.”

Peacock was the inspiration behind Edward Abbey’s

legendary fictional character Hayduke. The two writers and environmental activists were fast friends and frequent wilderness companions.

Writing about them has been equally unexpected. Was It Worth It?, Peacock’s sixth book, is a collection of essays and ruminations on both the costs and gifts of advocating for wildlife and wild places. The pointed question posed by the title is sharpened by what Peacock says is humanity’s systematic persecution of bears and wolves.

But he also thinks that the charity we extend to predators can offer us a lesson in persevering through existential change. “Bears are climate refugees, but we are too,” he says. “Human beings have to get their heads out of their asses and realize that we are a planet of refugees. Humans. Animals. Everything is in flux right now, and we will all need to move to the last hospitable places. We shouldn’t wish for greener pastures anymore, but for just enough habitat and land and food and resources to survive. We should see ourselves akin to bears more and more, not less. Our fates are truly mingled.”

Peacock contributes to a podcast from a makeshift studio in his Paradise Valley home.

The idea of shared reliance on wild places as both an ancient idea and an increasingly essential human requirement is at the core of Peacock’s writing and activism. He has advocated for the designation of federal wilderness areas, the conservation of wild bison, and for what he calls “creative mischief” to stymie the industrialization of landscapes.

Until recently, his calls to action have been based on hope, not doom. “I’m not a pessimistic person,” he says. “I take action, and I work really hard at fighting for wild causes that I consider worth fighting.”

However, climate change has dimmed his view: “The last chapter of the book is devoted to that beast of our time, and it’s coming for everything,” he says.

A Man Out of Time

Peacock acknowledges that his view of the planet’s future can sound singularly bleak. While he’s not particularly hopeful about humanity, he’s deeply devoted to humans. “The book is a byproduct of where I wrote it — sitting outside, either in the woods, or in the shade of Montana, or in the wintertime dust of Arizona,” he says. “It’s a product of so much productive anger based on my love of lost places. It’s a collection of beginnings and endings and, until I wrote them down, their meaning wasn’t revealed to me.”

If there’s a theme to the book, it’s that apex predators — the “equal-opportunity man-eaters,” he calls our cartoon versions of bears and big cats — make any place more interesting. It’s easy to imagine a primitive Peacock hiking amidst short-faced bears and sabretooth tigers, his proximity to mythic beasts filling him with purpose and productive fear. He hungers for the magnitude of nature, the “flush of life in any swarm, flock, or school of wildness.”

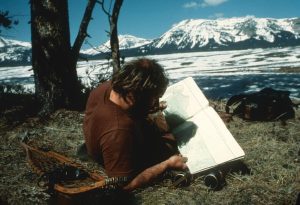

Where are the bears? Peacock studies a Yellowstone map in the spring of 1978. Photo courtesy of the Peacock family collection.

“The force of animal multitude, that’s something not enough people experience,” Peacock says. “If you wanted to speculate on the origins of human culture and language, that’s how it started, [as] ways to communicate the multitude of life we see in wild animals. We don’t have 60 million bison anymore, but outside my window in Montana, I can often see a couple hundred elk. That’s life-enduring material, whether 300,000 years ago or yesterday.”

Today, Peacock is a man out of time, ready to fight the conveniences that make it easier for us to reduce that multitude into smaller units. “I’ve been really lucky,” he says. “I’ve glimpsed the edge, that quiet forest where something predacious is going on. You sense an animal that’s hunting you. Everything gets quiet. It doesn’t happen very often, but it’s the universe of our evolution as humans, the foundation of our relationship with the world. That’s an experience worth protecting.”

You can also read Peacock’s book, which he expects will be his last, as a coda. “I was in a hurry to be done,” he says. “I wanted to put a cap on it, just in case I croaked or fell off a mountain or whatever. I’m catching glimpses of my own mortality. I have some time, I imagine, but I don’t count on it anymore. I’ve never been cautious, but I find myself being a lot more cautious these days, just for the useful reason that I want to hang around. I have family, a granddaughter. And a couple dogs. So you need to get your work done and you need to tell the people in your life who are important to you that you love them. Don’t leave anything unturned.”

As for the prevailing question of the book: Was his path as a wilderness warrior worth the miles and the mischief? To answer that, he guides the reader to exquisite moments of multitudinous wildlife, to flamingos boiling out of a Namibian oasis, scores of javelina flushing across the high mesas of Arizona, and a grizzly walking through a milling herd of grazing elk.

No Comments