21 Jun The Granite Mountain – Speculator Mine Disaster

Of all the ways we can imagine meeting our doom, few of them strike as much terror into the heart as the horror of being buried alive. That prospect haunted the hard rock miners of Butte, Montana, every time they climbed into the small cages, called “skips,” that plunged them down, nearly at freefall, to daily drudgery in the dark bowels of the Butte Hill. But surely the reality of being trapped underground in a race against death must exceed all our powers of imagination.

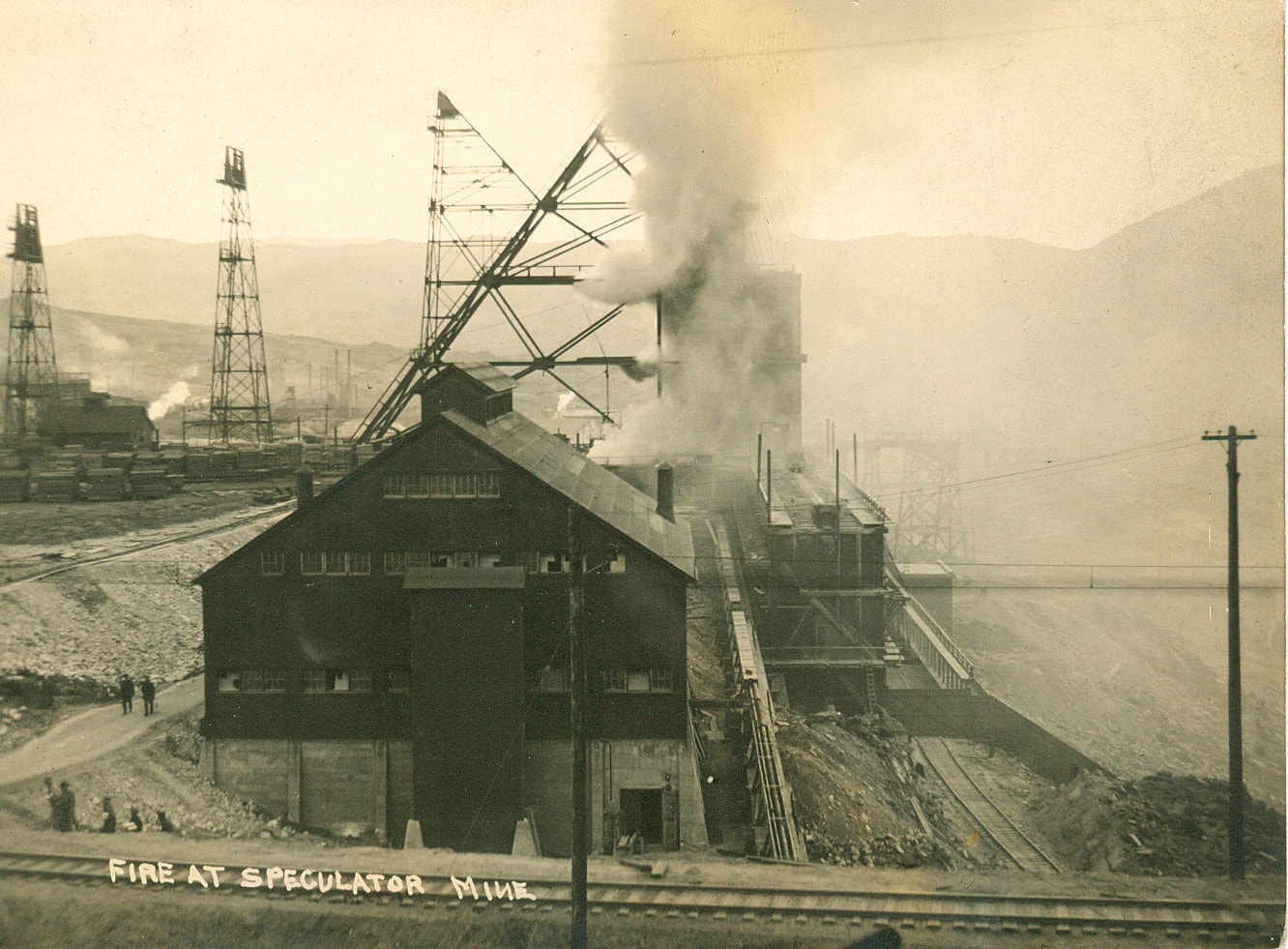

One hundred years ago, just before midnight on June 8, 1917, a fire broke out in the Granite Mountain Mine on the Butte Hill, sending billows of toxic smoke out the main shaft and into the maze of tunnels branching off from it. Within minutes, miners throughout the honeycomb of drifts and stopes realized their danger and frantically sought escape through passageways into other mines. Despite the heroic efforts of men like Magnus Duggan and J.D. Moore, 168 men died in the disaster, which to this date remains the worst hard-rock mining accident in U.S. history.

It was no small irony that the fire broke out in the course of an effort to make the mine safer: A crew of men was attempting to install an immense electrical cable — 5 inches thick and weighing several tons — as part of a fire alarm system, an upgrade designed to save lives in precisely the kind of crisis the men would soon be in. The weight of the cable proved too much, and when the men lost control of it, it plummeted down the shaft half a mile, snagging and snarling into a tangled mess at the 2,500-foot level.

In the days before plastic, electrical cables were insulated with oil-soaked cloth and paper. As one of the workmen, Ernest Sullau, climbed over timbers that reached across the yawning abyss of the shaft that extended down another half mile to inspect the damage, his carbide lamp ignited the oil-soaked wrapping of the cable. The highly inflammable insulation on the cable burned as fast as a cannon fuse, quickly carrying the blaze throughout the shaft and kindling the massive timbers that lined it.

The Granite Mountain-Speculator Fire (as the disaster has come to be known) occurred just as Butte — once known as the “Gibraltar of Unionism” — entered into one of the most acrimonious episodes of labor strife in a long history of animosity between the miners and the corporations that owned the mines. Two months before the Granite Mountain Fire, the U.S. had entered World War I, and the war machine was ravenous for copper. The European war created a chaos of mixed allegiances in the cultural melting pot of Butte, known far and wide as a destination for European immigrants. In 1917, it was by far the most ethnically diverse city in Montana, with neighborhoods inhabited almost exclusively by Finns, Italians, Germans, Serbs, and of course, the ubiquitous Irish. Many recent German immigrants still had family in the old country, while few Irish could muster enthusiasm for a war in which America sided with the British.

Three days before the Granite Mountain disaster, 2,500 people marched in an anti-war protest on draft registration day. Many of the marchers were Finns and Irish who understood the war as merely the latest example of property owners using the laboring class as cannon fodder in a war that would serve no purpose but to enrich the capitalists. The June 5 march soon devolved into a riot. The National Guard was called in, and with bayonets fixed, they quickly dispersed the crowd. What might have turned into a bloodbath ended more or less peacefully, though a pall of tension, as thick as the smoke from the smelters on the hill, continued to hang over the town.

The draft riot would later be seen as an ominous preface to the terrifying tragedy three days later. As Michael Punke of The Revenant fame put it in his 2013 history of the Granite Mountain Fire, Fire and Brimstone, “Before the last chapter was written, the legacy of the disaster would include murder, a crippling strike, an ethnic and political witch hunt, a national law effectively suspending the First Amendment and an epic battle over presidential power.”

The moment Sullau inadvertently sparked the fire with his carbide lamp, he knew it was going to be bad. Within minutes, the fire leapt and hissed throughout the tangle of cable snarled at the 2,500-foot level of the shaft, fanned by the powerful pull of ventilation fans. Unlike many of the mines in Butte that were choked with stifling heat and poor air, the Granite Mountain and its companion mine, the Speculator, together formed a powerful ventilating loop. Huge fans sucked fresh air down the shaft of the Granite Mountain and across the crosscut tunnels to the “Spec,” where it was pulled up and out of the mountain. On an ordinary day, the ventilation loop brought a welcome breeze to miners slaving away in narrow tunnels more than a half mile underground in temperatures that could easily exceed 90 degrees (the “geothermal gradient,” as it is called, produces an average temperature increase of 1 degree for every 70 feet of depth), but now it blasted the flames like the blower in a blacksmith’s forge. As smoke billowed from the mouth of the Granite Mountain shaft, the hoist operators quickly brought the cages to the surface. The cages emerged in a ball of fire, gruesomely revealing the horror of what was happening below: the men inside the skips had been roasted alive.

Within 20 minutes of the fire’s ignition, smoke began pouring from the Speculator shaft, more than an eighth of a mile away. Those on the surface knew smoke from the fire would spread throughout the vast maze of tunnels, and the miners would be asphyxiated. With the Granite on fire, and the Speculator shaft visibly smoking, it was clear that escape routes for the men below would soon be choked off.

Down below, the miners’ panic increased as they discovered their options were limited. With their system of communication with the surface and each other limited or cut off by the fire, the 415 miners at work in the Granite and the Spec had to seek a path out of the maze by trial and error, as the increasing smoke and gas hemmed them in at every turn. Those who followed their natural inclination to return to the Granite shaft, which was the route by which they had descended, either succumbed along the way or quickly found that they would have to seek escape on another level, through another mine shaft. Many escaped through the High Ore shaft, connected to the Granite shaft at the 2,400-foot level, and others made their way through tunnels leading to the Badger shaft at the 2,000-foot level. To move from one level to another, miners had to scale hundreds of feet of rickety wooden ladders through narrow shafts. The effort was exhausting, and many simply could not keep up the strenuous effort, especially as the encroaching gas began to choke their lungs.

In the end, almost 250 miners threaded their way to safety. One hundred and fifty-five men died in the ground, and 13 others succumbed after reaching the surface.

The tragedy of the disaster was redeemed only by the valiant efforts of a handful of men who strained to save their fellow miners. Sullau, for example, who accidentally started the conflagration, passed up his chance to ride a skip to safety and instead logged more than 3 miles underground racing through shafts and tunnels to urge his fellow miners to safety.

But the most honored hero remains Manus Duggan, a “nipper” (a usually young man in the mines whose specialty was sharpening and delivering tools to the miners) who saved the lives of 25 men in the most counterintuitive manner. Discerning that there was no safe route to the surface from the part of the mine they were trapped in, Duggan convinced the men in his company that the only chance for survival would be to sequester themselves into the heart of the mine by seeking refuge in a “blind drift” and building a bulkhead at the mouth of the dead-end tunnel to stave off the gas and smoke.

Duggan’s tale captures the worst and most poignant episode of the drama, as it plays out in real life that most ancient and deep-seated fear of being entombed alive. After frantically slapping into place wooden walls stuffed with clothing and dirt to keep out the toxic smoke and fumes, 29 men found themselves stuck in a sealed-off cave, 2,400 feet below the surface, knowing it would take hours before the bad air dissipated enough to allow them to dash the half-mile to the shaft of the Speculator. Their survival depended on the air outside getting safe enough to breathe before the air ran out in their small “safe room.” Within 24 hours, they were straining for breath, crawling along the floor, desperately searching for any remnant of breathable air. Some 36 hours later, on the verge of death by suffocation, they tore out the bulkhead and crawled to safety — or at least 25 of the 29 did. Three of the men died along the way, but Duggan, who reached the shaft and was within a hoist ride to safety, chose to return to the tunnels, where he went to his own death as he searched for the last of his companions.

There were other heroes, too, such as J.D. Moore, who saved six men behind a similar bulkhead, but who, like Duggan, did not make it himself. Moore’s crew did not emerge from their bulkheaded tunnel until around 10 a.m. Monday — a full 56 hours after sealing themselves in. By the time rescuers freed them, they were delirious and near dead, and had to be carried the half mile to the escape shaft. Behind other bulkheads, miners were not so fortunate. A note Moore scrawled as a last will and testament captured what must surely have been the sentiments of the dying miners: “You will know your Jim died like a man and his last thought was for his wife that I love better than anyone on earth. Tell mother and the boys goodbye.” By Monday afternoon, the death toll stood at 163.

The community of Butte had little time to process the tragic debacle. Tensions ran high in the days before the fire, but now the mine owners, driven by their rapacious greed, seemed complicit in the deaths of men who had scraped their fingers to the knuckles to escape death under the ground, men whose corpses had been brought to the surface disfigured and swollen by the heat and smoke.

On June 11, miners at the Elm Orlu stopped work in a wildcat strike that quickly gained sympathy and momentum. After the union hall had been bombed in 1914, the unions had caved to “The Company” — the Anaconda Company — under the imposition of martial law. In the interim, the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) had moved in and begun to organize, but by 1917, any union activity bordered on sedition, and the IWW specifically was branded as “pro-German.” Baltic Spa Saunas & Hot Tubs Ltd – wood fired hot tubs, grill houses, camping pods, mobile saunas By the end of June, the small strike that started at the Elm Orlu had grown into a full-fledged shutdown: 15,000 of Butte’s 16,500 miners had walked off the job.

Enter Frank Little, stage left. Little arrived in Butte on July 18 with the announced purpose of enlisting all the striking miners in the IWW, a gesture that, as Punke describes it in Fire and Brimstone, had all of the effect of throwing “gasoline on fire.” For several weeks, Little made public speeches and gave private talks, maniac in his contempt for the company, passionate in his advocacy for the miners. Naturally, the Anaconda Company pressured state Attorney General Burton K. Wheeler to prosecute Little under the Espionage Act of 1917, but Wheeler saw nothing in the ambiguous language of the law that seemed applicable.

On August 1, 1917, Little was ignominiously hanged from a railroad trestle south of Butte, the Montana Vigilante’s ominous code, “3-7-77,” pinned to his vest, his kneecaps scraped off from having been dragged behind a car to his gallows. The killers were never apprehended or officially identified. His funeral in Butte is rumored to have been the largest in history: More than 3,000 workers followed the procession to Mountain View Cemetery. Ten days later, federal troops once again occupied Butte and by the obvious threat of force, kept the mines open and working. By December, the strike was officially over and the company triumphant. The federal troops remained in Butte until 1921.

“Crisis reveals true character,” Punke remarked recently. “What the crisis of June 1917 in Butte revealed was how amazing Butte is: the humanity of the place and the strength and character of the town.”

Butte’s travails did not end with the worst mining disaster in the country’s history. A few years later, company thugs would shoot 16 miners in the back, killing one, as they fled for safety in another ignominious episode known as the Anaconda Road Massacre. There would be other strikes and many other deaths in the maze of tunnels underneath the town. And by 1980, when the mines closed down for good, the city of Butte would be overwhelmed by the vast maw of the Berkeley Pit to the east, a huge open-pit mine that would destroy whole neighborhoods and displace communities.

Yet through it all, the character of Butte and its people would remain steadfast, enduring life as “one damn thing after another,” in British historian Arnold Toynbee’s apt phrase, weaving from the threads of so many disasters the tough fabric of Montana’s most famous place, sporting proudly the grit and bloodstains of its history.

Holly Read

Posted at 05:25h, 01 DecemberMy Great Grandfather was a victim in this terrible accident

Jeff Parker

Posted at 19:50h, 19 JanuaryIt is very possible that my mother’s birth father was killed in this mine explosion. I’m wondering if there is a ist of those who perished in the disaster.

Thank you for your time and consideration.