23 Jul Image of the West: George Catlin’s American Buffalo

THIS SUMMER THE NATIONAL MUSEUM OF WILDLIFE ART is proud to partner with the Smithsonian American Art Museum to present 40 original paintings by explorer-artist George Catlin. Catlin was one of the first artists of European descent to chronicle the massive herds of buffalo that once roamed the Great Plains. While Catlin was primarily interested in depicting the ways of the native tribes he encountered in the North American interior, many of his works directly or indirectly incorporate buffalo, on which many tribes relied for food, clothing and shelter.

Catlin began his professional career as a lawyer, but soon turned to painting. In 1826, he saw a delegation of American Indians in Philadelphia and became fascinated by their appearance and culture. He vowed to record their life ways before they were completely altered by European incursion. By 1830, he was making his first of five expeditions into the West to gather material.

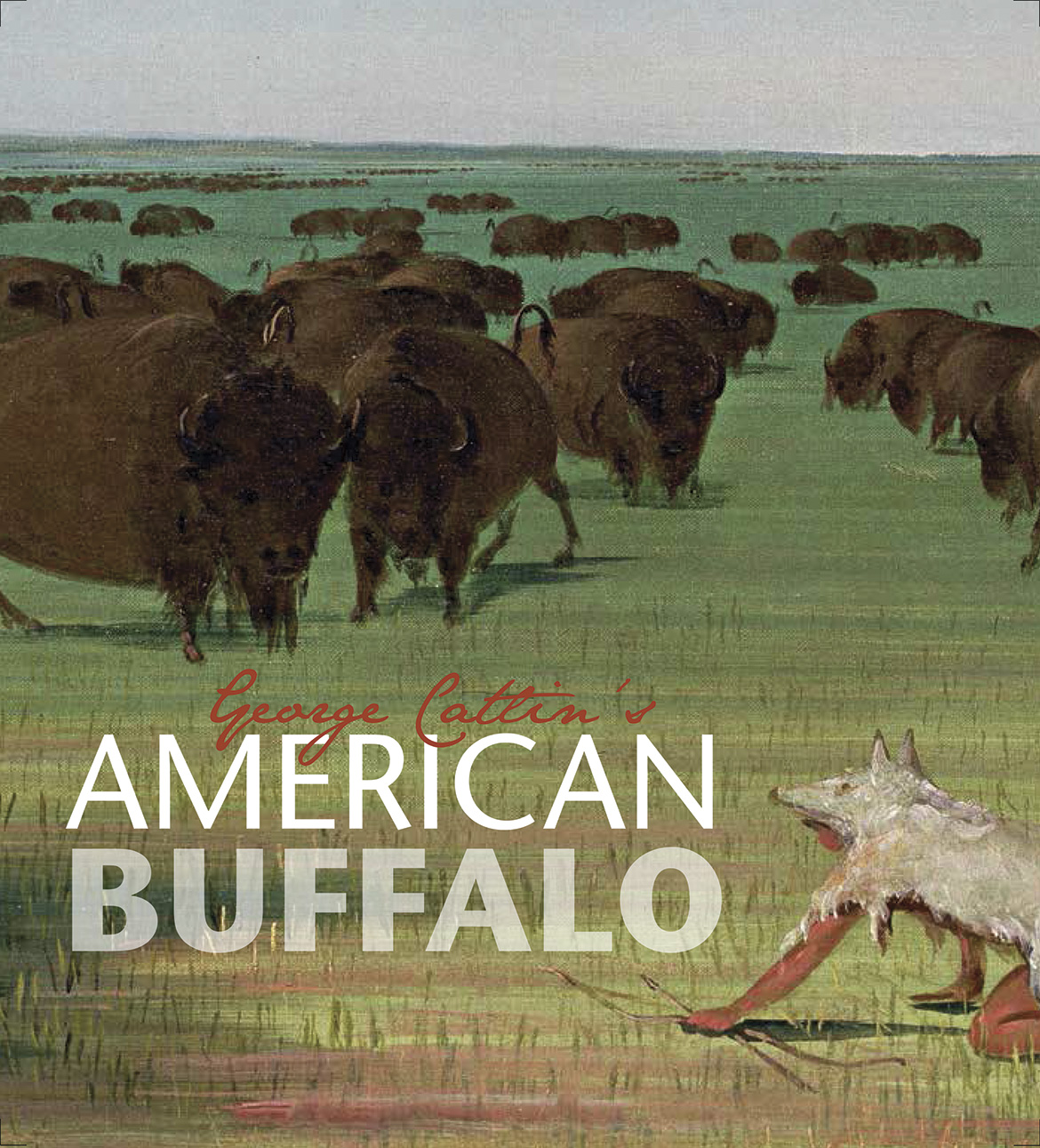

Buffalo were still plentiful when Catlin made his westward expeditions, but he sensed even then that without some greater measure of restraint on the part of advancing Europeans, buffalo would soon be eradicated from the plains. His warnings went unheeded and within 50 years buffalo numbers had dropped from millions to only a few hundred. This decimation had a tremendous impact on many Plains tribes, whose reliance on the buffalo left them increasingly without their primary sustaining resource. After Catlin’s images became widely known on the East Coast and in Europe, the iconography of the buffalo grew to symbolize both the bounty of the American wilderness and the tragic squander of that gift thanks to the advancing tide of civilization. Catlin’s Buffalo Bull, Grazing on the Prairie epitomizes this vision: wild, iconic and tragic at the same time.

The catalogue accompanying George Catlin’s American Buffalo delves into the artist’s work, but also connects the issues with which he was concerned to contemporary matters about sustainability, conservation and the environment. The following is an excerpt from the catalog essay, a brief personal narrative about how Catlin’s work connects with us today.

I sit on a small jet taking off from Jackson Hole, Wyoming, just south of Yellowstone National Park. Yellowstone was the epicenter of buffalo recovery in the late 1800s and is currently home to a herd numbering about 3,000. I am headed to Oklahoma City, near the largest remaining parcel of tallgrass prairie in the United States, which is home to about 2,500 buffalo. Much of the land between these two places provided habitat for the millions of buffalo that once roamed America’s Great Plains. And, in most places, where there were buffalo, there were American Indians, who relied on these animals for food, shelter, and clothing.

Flying at 40,000 feet, going 500 miles an hour for three hours, I am struck by the sheer scope of the buffalo’s former habitat. An estimated 30 million of the big, burly beasts inhabited the ground beneath the sky and clouds I fly through, populating the open lands stretching from Mexico to Canada. Relatively few explorers of European descent saw these great herds; fewer still recorded what they saw for others to see, bearing witness to the incredible sight of a landscape blackened by living, breathing buffalo (or, as they are properly known, bison). George Catlin, one of the first artists of European descent to travel up the Missouri River through the northern range of the buffalo, not only saw it, but he also recorded it in word and image. His stirring words and vibrant paintings resonated with audiences in the eastern United States and Europe during his time and reverberate with meaning even today.

As the plane flies over the rugged Rocky Mountains and enters the airspace above the flat farmlands of the American plains, the landscape transforms from snowcapped mountains and lush river valleys to a series of cultivated squares and circles in different shades of green and brown, indicating different crops or different harvest cycles. This is not prime forage for free-ranging herds of buffalo, but is instead a landscape divided, fenced, irrigated, seeded, fertilized, and harvested for the benefit of humans — a region that has been described as America’s Breadbasket. Catlin had a different idea of what this landscape could look like and how it could function. His idea is as complicated as he was, fraught with contradictions and biased by the tenor of his times, but his idea also speaks to contemporary concerns about a sustainable way to use the land also known as the Great Plains.

Though Catlin did not have the benefit of modern air travel, in his two volume book, Letters and Notes on the Manners, Customs, and Conditions of North American Indians, he projected himself into the sky, “lifted up upon an imaginary pair of wings” high above the continent. At first he saw an Edenic vision of “vast, and almost boundless plains of grass, which were speckled with the bands of grazing buffaloes!” But then his vision turned dark, as hunters of all varieties filled the land and hunted the buffalo to their death. These two opposite visions repeat throughout his Letters and Notes: One vision represents the way he thought the land might be if left alone or protected; the other represents the way he assumed the land would be, given the advancing tide of European American settlement.

The essay continues with an investigation of how a part of Catlin’s vision for “what might be” has the potential to come true today as various parties including American Indians, wealthy ranchers and conservationists coalesce around a land-use policy for the Great Plains that would reintroduce buffalo and provide a sustainable and healthy food source for generations to come.

The exhibit and portfolio section of the catalogue take a closer look at how the buffalo was incorporated into the lives of tribes such as the Mandan, Sioux, Crow and Comanche. Catlin was careful to record the variety of ways tribesmen hunted buffalo, a few of which recall methods employed before horses made a huge impact on Plains Indian culture. He also depicted buffalo habits and habitats, displaying an interest in the animal as something other than a source of food or robes. Finally, in his best-known work, Catlin painted striking portraits of the people he encountered, many dressed in their finest decorated buffalo robes.

Catlin’s work helped lay the foundation upon which much of the mythology of the Plains Indian and the American buffalo was built. His images depicting the deep connections between American Indians and buffalo remain unsurpassed in the art historical canon and his writings provide further insight into his perceptions. Because Catlin, more than any other early American artist, eloquently recorded and then published his thoughts, examining his images and text provides a rich opportunity to investigate essential aspects in the development of the American frontier ethos.

George Catlin’s American Buffalo is organized by the Smithsonian American Art Museum in collaboration with the National Museum of Wildlife Art in Jackson Hole, Wyoming. Generous support for the exhibition has been provided by Mary Anne and Richard W. Cree, and Lynn and Foster Friess. Additional support for the exhibition and the publication was provided by the William R. Kenan Jr. Endowment Fund and the Smithsonian Council for American Art. Support for Treasures to Go, the Museum’s traveling exhibition program, comes from The C.F. Foundation in Atlanta, Georgia.

Editor’s Note: Excerpted from the Catalog, George Catlin’s American Buffalo (Smithsonian American Art Museum in collaboration with Giles, 2013), the book is available at local bookstores and online for $45.

George Catlin’s American Buffalo Tour Itinerary:

National Museum of Wildlife Art: Jackson, Wyoming

May 10 – August 25, 2013

Palm Springs Art Museum: Palm Springs, California

October 1, 2013 – December 29, 2013

C.M. Russell Museum: Great Falls, Montana;

May 31, 2014 – September 14, 2014

Mennello Museum of American Art: Orlando, Florida

October 4, 2014 – January 1, 2015

Reynolda House Museum of American Art: Winston Salem, North Carolina

February 12, 2015 – May 3, 2015

- “Buffalo Chase, a Single Death” | Oil on Canvas | 1832 -1833

No Comments