25 Aug Images of the West: From Prostitutes to Polkas

SHARP ROCKY CLIFFS RIDE ABOVE Silver Gate, Montana, a tiny smattering of log structures just outside the northeast gate of Yellowstone National Park. Only seven year-round residents make their home in the narrow meadow between mountains. I have had the pleasure of recreating in this unique town since I was 12 years old. I have been a visitor, an employee and employer, a barmaid and waitress, business and property owner, a school bus driver, and a staff member in the operations tent during the 1988 Yellowstone fires. I have loved Silver Gate from my first encounter 57 years ago. Since then, I have wanted to be here most of the time; even when I was privileged enough to take a European trip at 18, I longed to be in Silver Gate. It is my heart-home.

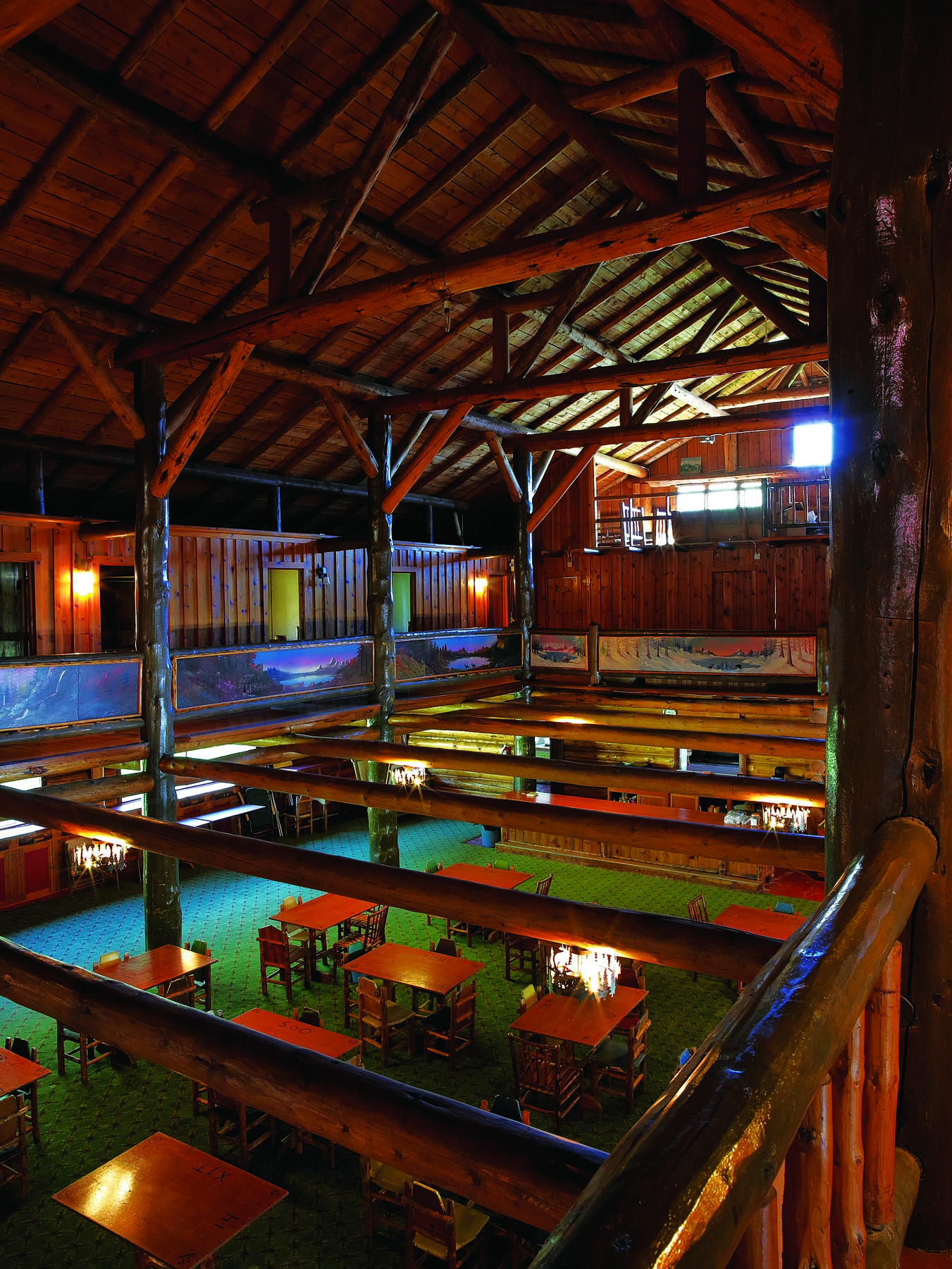

At the far west end of Silver Gate sits an old dance hall, the Range Rider Lodge, known simply as the Rider to locals. In my teens I read there, met friends by the fire, sometimes pouted, danced and worked as a hostess. For a few years I was a barmaid jumping chairs to serve a very full house. I loved the place so much that I chose it for my wedding ceremony and in 1966 I became the first bride ever married there. Now, as the co-owner of the Log Cabin Café across the street, I am a fellow businessperson and neighbor.

Over the years I have witnessed many mutations of the Rider. Some of them subtle, some dramatic. Just as the Rider revised itself with each new owner, so did my own experiences alter me. The building’s changes resonate with the changes in my life, my era and the American culture during the late 20th century. This is the story of those changes.

Road crews finished the Beartooth Highway (US 212) in 1937, but it remained gravel. P.R. Gorham, a hotel owner from Scobey, Mont., saw an investment opportunity in the road connecting the high alpine Beartooth Mountains with undiscovered northeast Yellowstone. He gambled that the highway would bring crowds of tourists over the nearly 11,000-foot pass on their way to Yellowstone National Park. The 68-mile byway, a marvel of 1930s engineering, rises 2,800 feet in 12 miles. Treacherous zigzags and switchbacks traverse alpine territory with incredible vistas and hairpin turns that have nauseated many a traveler. But, Gorham won his bet. The highway did bring tourists arriving over the Beartooth Pass in their Model Ts to play and stay in his “resort,” which is now the Range Rider Lodge.

Gorham brought in construction crews and hired locals to create a spacious indoor “playground” offering gambling, drinking and prostitution. Production crews built the Gorham Chalet, as it was then called, using whole logs hauled from the surrounding forest. It took brute strength and mules with a block and tackle to hoist the logs into place.

Pine poles provided the materials for interior furniture, much of which remains in the Rider today. Gorham hired a furniture maker rumored to have had so violent a temper that he threw tools and broke furniture into kindling when things went wrong. Amazingly, given the Montana winters at 7,389 feet, the Gorham Chalet restaurant, bar and tiny rooms upstairs opened on time in 1938, offering pleasure to soothe Depression-era distress.

Its 1930 roots in gambling and prostitution are still evident in the building’s architecture; the huge barn-shaped structure dominates tiny Silver Gate. Each door to the 20 rooms bordering the second story catwalk have a woman’s name on it. Neither elaborate nor spacious, only three things complete the furnishings in each room: a bed and a small dresser with a pitcher on it.

Beneath the catwalk above the dining room, log-framed oil paintings remain preserved. Created by an itinerant painter named Pletan, these images feature the style and colors of mountain and lake scenes popular in the ’40s and ’50s. Their quaintness speaks of a bygone era and balances the huge fireplace at the opposite end of the lodge.

On each side of the fireplace, saloon-style swinging doors practically shout that gambling took place behind them. Back in the day, with law enforcement a sweet distance away, either over the Beartooth Pass or through Yellowstone Park to Gardiner, illegal activities flourished here. It’s easy to picture gamblers lined up at the bar and ladies of the night waving from the front balconies to their customers. In my mind, the “ladies” are dressed in plenty of black lace and red, yellow and pink satin.

My own times in the Rider conjure up images of myself in costume too. My dress signified my personal values, especially my impatience with the cultural limitations for women in that time. Then, as now, I was often unwilling to accept gender prescriptions. Like Rosie the Riveter, I rebelled against them in the way I dressed.

Early in 1960, my first year as an employee in Silver Gate, I was required to wear a dress for work. But as soon as my shift ended, I donned a long, dark coat and a very large-brimmed cowboy hat. I made my own statement striding confidently through the double doors of the Rider to meet friends in that get-up.

Later, as a hostess at the Rider, dressing “like a lady” for work was also obligatory. Dresses were as common then as they are uncommon now. Jeans or shorts are the garments of choice now for virtually everyone in the valley, a fact that certainly points to a sea change in ideas about how women should dress and behave.

In the latter half of 1966, I put aside my cowboy hat temporarily, giving up my railing against gender requirements in service of a formal wedding. I chose a long ivory linen dress that matched the elegance of the Rider at that time. I walked down a white carpet to the fireplace, then we enjoyed dinner with white tablecloths, live music and a waxed dance floor. It was a fleeting expression of refinement for both the building and me!

In 1969, three years after our wedding, my husband and I bought the Timberline Motel at the opposite end of Silver Gate. We did almost anything to keep us afloat, including working in other motels and bars. I was that barmaid serving a jam-packed house every weekend in my favorite red-and-white Coca-Cola pants reserved for those weekend dance parties at the Rider.

The dances may have been regular but they sure weren’t dull. Some dances were outrageous, but parties weren’t the only activities there. The Range Rider was a great community gathering place for years. It hosted diverse activities, including regular talks by park rangers and nature films. Then there was the time that a group of us gathered to learn the polka. I can’t remember what I wore for that occasion, but I think it was mostly a smile. I never did learn to polka, though we all sure laughed a lot.

The Range Rider is not open much now. These days some people tell the story that the place is haunted. Could it be its ghosts see all of us in turn, from tempting prostitutes to a young bride in wedding finery, from dances to official updates during the 1988 fires, from motorcycles in the bar to polka lessons?

The Rider is a place where memories glide over the events of my life, the people I have been and the clothes I have worn to express those selves. They take me from rebellious teen to feminist scholar. My understanding about current ideas regarding women’s place in the culture of our time have developed there, brought into play with this building and its mystique, some 50 years ago. Now, at almost 70, I dance with ease, one of the many spirits here.

- The cowboy motif is highlighted with the room’s curtains.

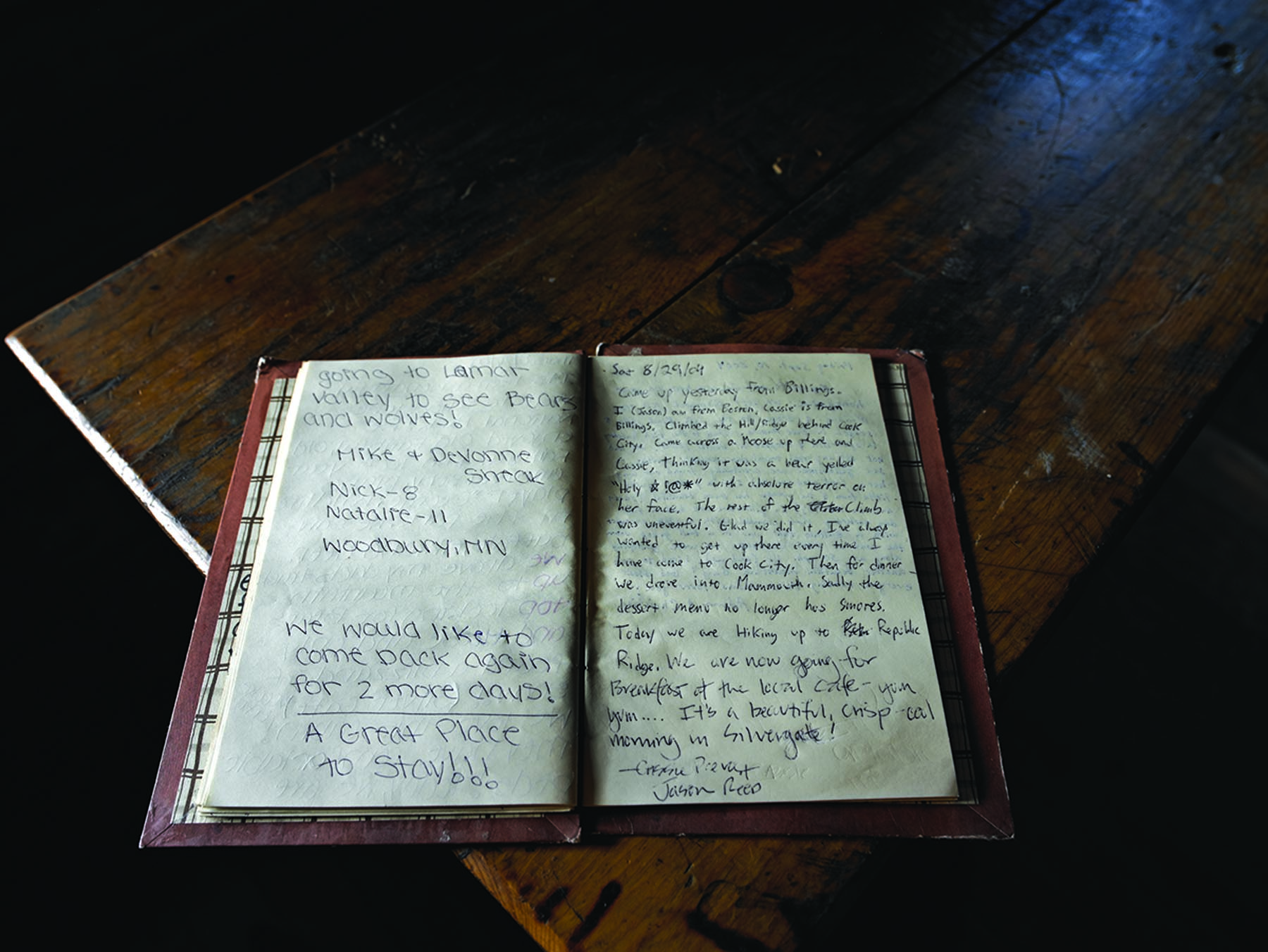

- The guestbook from room #6 praises the virtues of the Range Rider and Yellowstone National Park.

- The rustic façade and sign of the massive log structured Range Rider Lodge, built in 1938.

- Aluminum wildlife décor hangs in the men’s room.

- All room numbers are rough cut and named after women.

Hardy Pruuel

Posted at 00:57h, 07 December,I worked for the NPS while in college during the summers of ’67, ’68, & ’69 on the road maintenance crew on the Beartooth Highway. Spent many Saturday nights at the Range Riders to have a few beers. As there was no band there at that time, the bar tender would let me play the old upright piano which was on a very small stage in a the bar area. The patrons loved any live music they could dance a 2-step to, and since I mainly played boogie, blues, and ragtime tunes, they didn’t mind it at all. And many times I’d notice a free beer would be placed on top of the piano. Great times. There was an elderly couple, George and Ann Herman, who ran the Silver Gate post office, which was across the street from the Range Riders. I had PO Box #1, and would stop in a couple of times a week to get mail, and they took a liking to me and would invite me in for coffee and to chat. They were so nice.