12 Feb Finding Another Way

A trail re-route to save a species

The 1,200-mile Pacific Northwest Trail, that stretches from Glacier National Park to the Pacific Ocean, has the potential to put the diminishing Yaak grizzly population at risk.

Last year was the 50th anniversary of the National Trails Act; this year seems a good one to stop and applaud the foresight of bipartisan leaders of back-then who realized the American public, in times of stress, would seek clarity in the wide-open spaces of the great outdoors, a land seemingly beyond the throw of firelight from the national and global bonfires that remind us of our need for the solace of nature — and of the power wild country has to shape the best in us. What is wild country? Writer Doug Peacock describes it best: “Country where things live that can kill and eat you.” He says it only partly tongue-in-cheek, for he is, after all, speaking of humility — a quality as rare some days as the wild country itself.

The grizzly bear population in the Yaak Valley is on the brink of extinction. Less than 30 bears now call the Yaak Valley home.

For more than 20 years, I’ve worked with a small community service and conservation organization — the Yaak Valley Forest Council — in Montana’s largest and most northwestern county, Lincoln. The million-acre Yaak Valley, in the most northwestern corner of the county, is Montana’s only rainforest. While the rest of Western Montana was carved by retreating glaciers, the vast majority of the Yaak (the Kootenai word for “arrow,” due to the shape of the Yaak River, which charges down into the Kootenai River, the largest tributary to the Columbia and lowest elevation in Montana) sat lower, beneath thick blue ice in the new world of glacier-killing heat.

The Yaak emerged late, the last to come out from beneath the ice sheet, like a second-chance Garden of Eden: a do-over. Nothing has gone extinct in the Yaak since then, but our grizzly bear population is at the edge of vanishing; a 2012 DNA study showed only 22 bears remain, and every one of them also travels back and forth into Canada. (Official estimates now range from 25 to 27.) Females do not breed until 6 years of age, and as such are the second-slowest reproducing land mammal in North America. The Yaak’s grizzlies live as if on an island, cut off from other populations in Yellowstone and the North Cascades, and even the nearby Cabinet Mountains. (The U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service has combined the two populations, the Cabinet and the Yaak, into a single entity for management purposes, despite the fact that there is no documented genetic exchange between them and only four recorded instances of a grizzly passing from one ecosystem into the next.) The loss of one breeding age female in the Yaak could easily determine whether they recover or blink out, like a fire gone cold.

The Yaak emerged late, the last to come out from beneath the ice sheet, like a second-chance Garden of Eden: a do-over. Nothing has gone extinct in the Yaak since then, but our grizzly bear population is at the edge of vanishing; a 2012 DNA study showed only 22 bears remain, and every one of them also travels back and forth into Canada. (Official estimates now range from 25 to 27.) Females do not breed until 6 years of age, and as such are the second-slowest reproducing land mammal in North America. The Yaak’s grizzlies live as if on an island, cut off from other populations in Yellowstone and the North Cascades, and even the nearby Cabinet Mountains. (The U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service has combined the two populations, the Cabinet and the Yaak, into a single entity for management purposes, despite the fact that there is no documented genetic exchange between them and only four recorded instances of a grizzly passing from one ecosystem into the next.) The loss of one breeding age female in the Yaak could easily determine whether they recover or blink out, like a fire gone cold.

And there’s trouble in the Garden.

For several decades, a hiker named Ron Strickland, with a proposal for a 1,200-mile Pacific Northwest Trail stretching from Glacier National Park to the Pacific Ocean, has lobbied Congress and the U.S. Forest Service (USFS) to authorize such a trail. The USFS and Fish & Wildlife have always turned him down on the grounds that a high-volume thru-hiker trail would have negative effects on the endangered grizzlies. But in 2009, after 31 years of rejection, the Pacific Northwest Trail Association (PNTA), founded by Strickland, succeeded in convincing Rep. Norm Dicks and Sen. Maria Cantwell of Washington State to attach a trail authorization as a rider to the must-pass 2009 omnibus spending bill. There was no consultation with nor knowledge by Montanans about Cantwell’s rider. It simply became law.

The resulting 1,200-mile trail passes from the Continental Divide in Glacier National Park through Western Montana, along myriad logging and paved roads in the Yaak, on its way to the Idaho Panhandle, and then through Washington to the Pacific where it would also connect as a spur to the immensely popular Pacific Crest Trail.

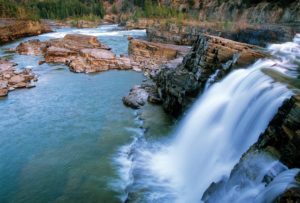

An alternative route runs along part of the scenic Kootenai River.

What does this have to do with fish or fishing? Little, yet. The few bears that remain are sleeping, as we read this. They will awaken, however, to another season of thru-hikers competing for what little alpine habitat exists in the low-elevation Yaak. It’s not a good mix, piling in thru-hikers on top of the most critical designated core grizzly habitat in the Yaak.

Fortunately, an alternative scenic route is possible, one that avoids designated core habitat for the threatened grizzlies in the Yaak. Conservationists in all three affected states (Montana, Idaho, Washington) are advocating to re-route the current trail. A southern scenic alternative near the Kootenai River would be an ethical choice for hikers, exposing them to the opportunity, if they wished, to re-provision in the rural communities of Libby or Troy, and to access the Kootenai River with its famed population of native rainbows. A southern route would also involve less “road-walking” than the currently authorized route in the upper Yaak’s grizzly stronghold.

I’m sure Dicks and Cantwell were unaware of the study authorized by Congress in 1980, with the findings by Charles Jonkel that a northern route as proposed by the PNTA would be harmful to Montana, while a southern route — down out of the mountains and through Treasure Valley, through cool cedar forests and along the idyllic Kootenai River before going back up into the Selkirks — would be the best alternative (other than no trail in Montana at all).

And it’s possible that current trail advocates, unaware of the 1980 study, also are not yet aware of the 2018 study by bear biologists Lance Craighead and Wayne McCrory, which resulted in similar findings: The existing alpine route in the Yaak is the worst possible route for grizzly bear recovery.

It would seem that a Washington-based nonprofit devoted to hiking in the great outdoors would want to take these scientific findings to heart and work with states like Montana to find a route that doesn’t put hikers and grizzlies in each other’s way, in harm’s way. I believe there is a hiker-ethos that would likewise consider it a value-added experience — knowing that their targeted route aided small economies and gave grizzlies a chance to recover in a place where they have not done so yet.

It would seem that a Washington-based nonprofit devoted to hiking in the great outdoors would want to take these scientific findings to heart and work with states like Montana to find a route that doesn’t put hikers and grizzlies in each other’s way, in harm’s way. I believe there is a hiker-ethos that would likewise consider it a value-added experience — knowing that their targeted route aided small economies and gave grizzlies a chance to recover in a place where they have not done so yet.

Unfortunately, the PNTA, partnering with the Forest Service (Region Six has been given directorship over the entire 1,200-mile trail), has been advertising unauthorized “alternate” routes, also through the heart of territory in the Yaak previously dedicated by the Forest Service as core grizzly habitat. The PNTA advertised the current Yaak route as providing hikers a chance for the humbling experience of “sleeping out with these incredible creatures.”

This is not the best way to recover the most endangered population of grizzlies in Montana. The southern scenic alternative would be more prudent for both bears and hikers. And without waiting for the Congressionally-required Comprehensive Management Plan to govern wherever a final trail is established, the Kootenai National Forest has proposed several large clearcuts on top of the existing trail, while Region Six (out of Portland, Oregon) has mischaracterized the southern scenic route as being on a highway. The Kootenai National Forest is proposing several new spur trails to the current route, also in Priority 1 critical designated core grizzly habitat, even as the Kootenai participates in re-route discussions with other parties.

Ironically, two wildfires in the Yaak Valley this summer took place on the existing route and the proposed re-route, respectively, burning thousands of acres in the area through which the thru-hikers would have been traveling without the ability to be notified. Local search and rescue volunteers agree that extraction efforts from the international border country where the Montana section of trail is located (both the existing trail and the re-route proposal) would be extremely problematic. As well, the fires will further concentrate our last few grizzlies in these burned areas, as they seek the pulse of higher nutrients distributed by the fire.

In this time of polarization to the point of Balkanization, the West has an opportunity to stand strong and make decisions that work across borders, across walls. Decisions made in Washington and Idaho regarding Montana need not necessarily precipitate a clash that results in the revocation of the Pacific Northwest Trail in Montana, though indeed, no trail in Montana might be the best option for grizzly bears, and even for timber interests. We owe the legacy of the National Trails Act to craft with care our decisions for a wild and rejuvenating future that accommodates not just our own species, but those others that are most endangered as well.

written by rick bass

No Comments