24 Jul Artist of the West: Sara Mast’s encaustic paintings explore the cosmos

EXPLORER. RESEARCHER. ASTRONOMER. Philosopher. Artist.

Sara Mast is all these things. Through her encaustic paintings she delves into the innermost constructs of the psyche and the outermost reaches of the universe.

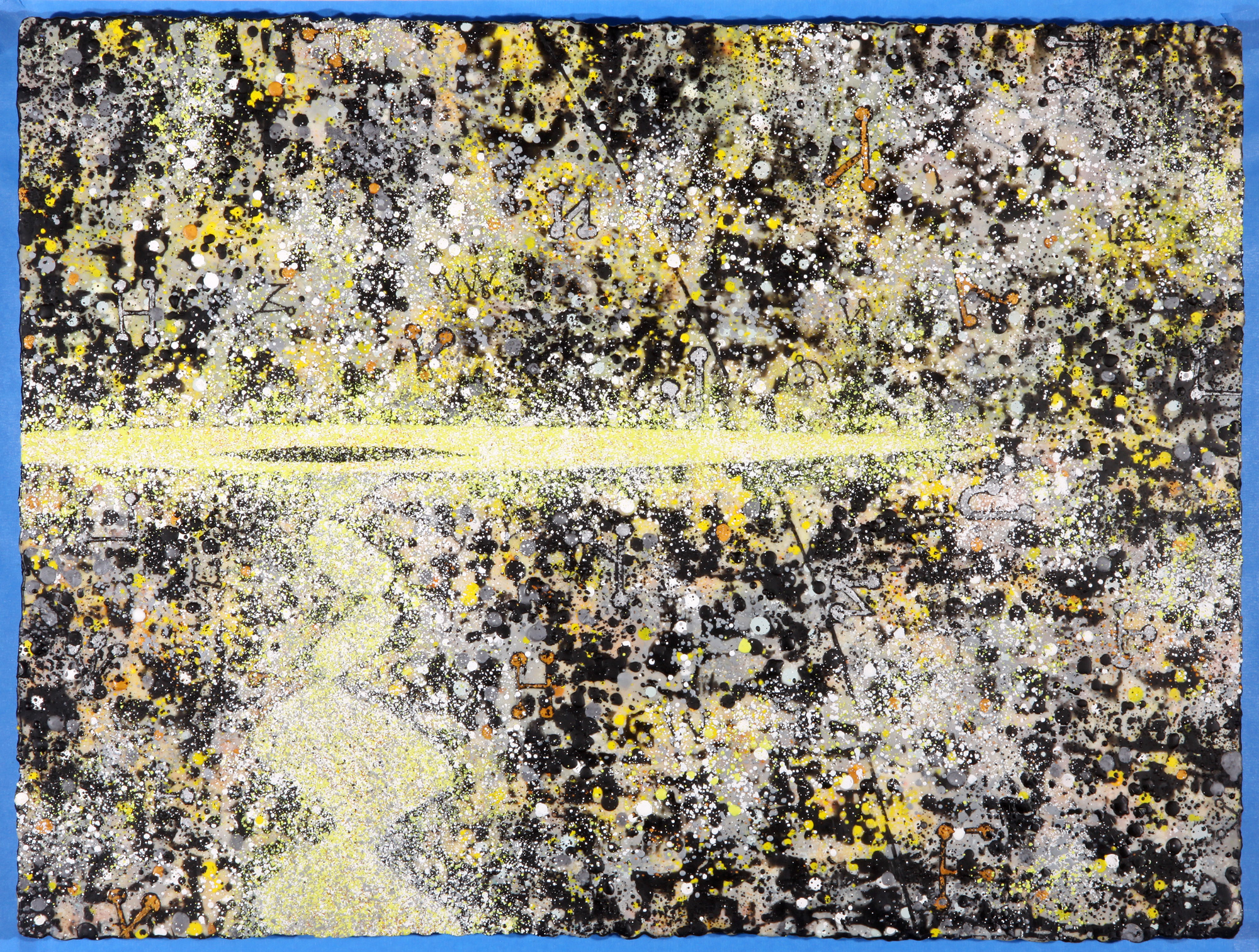

Separated from the world by a wall of windows, her studio, white as the clean slate, reflects the work she’s done and the work that’s yet to come. This is a period of transition from the outer world to the inner life, from macrocosm to microcosm, from the whole of the universe to the personal journey of her father. Only a few pieces from her last series linger on the back wall.

“There’s something in that one I want to remember,” she says, getting up from her desk, a separate workspace from her painting area. She walks over and puts a hand on the uneven surface, the built-up layers of wax overlaid transfers of star maps, ancient texts partially covered with paint and pigment.

With research books stacked around her laptop, Mast spreads the pages of a “sketch” book — a paper-bag brown composition book, its gridded pages densely filled with writing. “I write a lot,” she says, pointing to the five or six books she’s already completed this year. Opening to a section of yellow highlighted words, “It is cyclical, orbital, elliptical, spinning, spiraling all these movements describe the process of becoming.” Reading the small neat black letters is like peeking over the ledge into her creative mind.

“I’m thinking about the painting … the DNA piece,” she says. Then she opens a digital photograph of the double helix nebula, approximately 300 light years from the enormous black hole at the center of the Milky Way. “Things like this keep me wondering,” referring to the nearly impossible repetition of patterns in our own bodies to the heavenly bodies of the universe.

The studio brings to mind a late-candled evening from the scent of her beeswax, warm and fluid, sitting in electric pots. On her thigh-high work table about a dozen muffin-sized tins pool with melted wax and paint. Some of them solidified, with tilted brushes left like broken clocks.

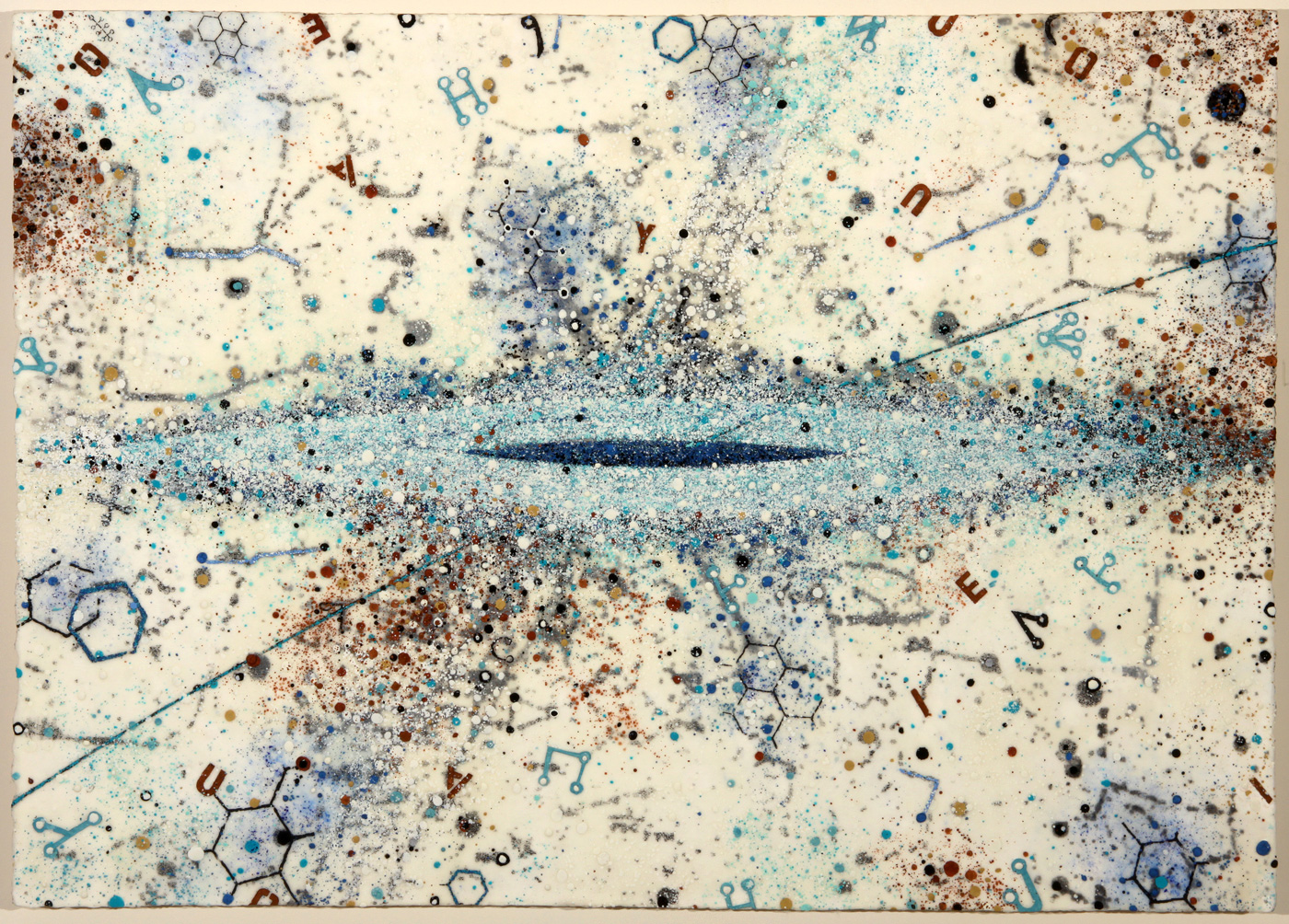

A 22- by 30-inch piece she’s recently started sits centered on the table top. Swirls of blue nebulas connected by invisible orbits. Dots of gold. A spattering of white. Mast presses a single-sided razor to the dark colored layer and begins to scratch, removing the darkest part, balling up the excess from the blade and rolling it into a ball before adding it to a pile — a tree-like mound of color-streaked spheres.

“The process is as much additive as it is subtractive,” Mast says, unearthing a black transfer symbol. “I forgot I had that under there … I kind of like it. I’ll keep it.”

And she stops scraping, moving to another blue splattered nebula. The encaustic process, the layering of wax and paint, allows her to isolate a particular area and take it to a different depth than other parts of the piece, something that would be nearly impossible with an oil painting.

In Montana, Mast is represented by Visions West gallery, but her work goes well beyond the borders of regional genre. Jackie Pernot, gallery director at Chicago Art Source represents Mast’s work. Pernot has an affinity for encaustic art, especially Mast’s.

“I have always been drawn to the unique characteristics of it, the smell, the warmth of the tone, the feel of the wax and the texture,” she says. “I think Sara Mast’s work is really unique … the way she uses details and her whole method of looking outward and inward simultaneously is intriguing.”

It’s also something her clients respond to.

“There are embedded symbols that pique your interest — just so many things you can linger on, things you can pull out of them over time,” Pernot says. “Mast’s paintings are rich, even if they’re somewhat open-ended. When I’m looking at her pieces some of them have that type of cave drawing feeling, but they are very scientific as well as historical, and they reference our current technology, which is also very interesting.”

Sometimes the more a piece speaks to the artist personally, the more relatable that piece becomes to the viewer. Such is the case with Mast’s work.

“Looking at it you certainly see the references she’s making to the universe and they do feel very personal at the same time,” Pernot says. “There’s a depth to her work. You have the feeling that it’s continuing beyond the surface and beyond the piece itself.”

Included in her current painting are ancient alphabet symbols, the Cabala’s Tree of Life structure, and “Buckyball” shapes (think soccer balls or geodesic domes).

Standing at her work bench Mast concentrates on the piece in front of her. At times her scraping is almost frantic: a focused erasure or a miner at last finding gold. At other times it’s slower, more exploratory. As she works she talks about a theory she’d read: “It was a theory on comets, how they bombarded the Earth and seeded our planet. At first scientists couldn’t believe that bacteria could survive the atmosphere, but then they discovered the outer shells were shaped like Buckyballs,” she says, explaining her inclusion of the objects, often at the center of the nebulas. “Like a protective seed’s shell.”

Soon to be included in this painting are the images from her father’s work.

“This is my new series,” she says. “I got a grant from Montana State University for a research project that’s related to my father’s life.”

Her father, an inventor and a physicist, worked for Theodore Edison (Thomas Edison’s son) for a few years and participated in the 1933-34 World’s Fair, A Century of Progress, in Chicago. She plans to incorporate her father’s work into her own, in a series she’s calling Following the Thread: Mapping the Inventive Mind.

“I want to experience science through my father’s experiences,” she says. “In my previous work I’d been thinking about the outer edges of the cosmos. Now I’m going interior and how my father’s perspective on science made me into an artist who loves science.”

She recently visited the Thomas Edison Museum in West Orange, Fla., and discovered that many of her father’s philosophical ideas about science and engineering were instilled in him when he met Thomas Edison as a youngster, and were reinforced later in his work with his son, Theodore.

“In contrast to the work of a scientist or an engineer, my life’s work as a painter is dedicated to probing the imagination,” she says. “I’m really looking for those connections between our own cosmology and science with everything from neuroscience to star charts and how we’re evolving along with our own perceptions of the universe and ourselves.”

Yellow-edged pages peek out from old file folders on her desk. A stack of notes, type-written on thin paper. These are her father’s original notations and thoughts.

“I’m very influenced by his designs,” she says. “They were sleek, very Modernist. They echoed the idea of spacecraft. He always said, ‘The best design is the simplest design.’”

As she works, taking away layers of wax she discovers a symbol from an ancient alphabet she’d transferred to the canvas in the early stages of the painting. The celestial alphabet from the Book of Raziel, where the lines of each letter stands for the spaces between stars.

“The idea that language comes from the stars is fascinating,” she says, moving her sharp razor more slowly, careful to only unearth the painting to a certain point and no further. “There’s so much information out there, our mind is not enough to understand it all. We need a mind/body/spirit integrated way of experiencing — you can’t get there from any one angle.”

Painter Catherine Courtenaye follows Mast’s work and believes Mast has gotten to a place where not many artists have been able to find.

“Her paintings embody her wide-ranging research and her own temperament: she’s truly passionate about astrophysics and contemporary painting, and also a fervent Jungian,” Courtenaye says. “She has forged a body of work that makes the collective unconscious visible and palpable — a feat with which generations of artists have struggled.”

Considering her latest series, which concentrated on her own cosmological perspective, Courtenaye feels Mast has some serious things to say about our world and beyond.

“Her recent paintings, suggesting the explosive fairy dust of cosmic beginnings and endings, create their own convincing reality,” she says. “They suggest a primal remembering, while peering into our shared future. Although her sources include ancient signs and symbols, and her chosen medium of wax and pigment is archaic, her recent paintings have a modern, fresh zing to them.”

If, as Joseph Campbell once said, “We need a new mythology for our time,” then perhaps we should be looking to the encaustic works of Sara Mast for those stories.

- Encaustic artist, Sara Mast.

- Ocean of Stars • encaustic on paper mounted on panel • 22″ x 30″

- OUR BIRTH • encaustic on paper mounted on panel • 22″ x 30″

- “Eye of the Storm” | Encaustic on Paper Mounted on Panel | 32 x 40 inches

No Comments