11 Dec Artist of the West: The Ways of the Old West

In the small town of Channelview, Texas, a young boy stands on scaffolding and reaches up to paint the white front tooth of a smiling woman who is 24 feet tall. It’s 1967, and Gary Lynn Roberts is working for his family’s sign painting business, creating a billboard that advertises the latest attraction at the drive-in movie theater. Since age 11, he’s been painting window displays and hand-lettering advertisements, from the san-serif specials on grocery store windows and Humphrey Bogart’s face on a “Casablanca” movie poster, to giant hamburgers and Easter bunnies on storefronts, and a towering elephant on a water tank. That early practice paid off, and by age 14, Roberts was selling his Western canvases at regional art shows and was a professional fine artist by age 22.

Ruth 1:16 | oil | 60 x 48 inches

“I love God. I love my family. I love this country, and that’s what I try to depict in my paintings. If you know me, you know that’s who I am,” he says.

Born in 1953 as a third-generation artist and the son of noted Western painter Joe Rader Roberts, Gary Lynn always knew the creative life was his calling. “Once someone asked my father, ‘How long has Gary Lynn been in painting?’ And he said, ‘I don’t know how long he’s been painting, but I used to wipe my brush on his diaper when he crawled by.’ That’s how long I’ve been around painting. It’s all I ever wanted to do,” Roberts says.

Today, the Montana-based artist mixes Realism with Impressionism to create narrative works that depict the quiet moments and melodramas of the early frontier in the American West. He doesn’t paint historical scenes, but his work reflects the period between the 1870s and early 1990s when the Union Pacific was wending its way westward, barbed wire was patented, and frontier characters met the Native American tribes already living off the land. His childhood experiences in Texas, training horses and participating in rodeos, added to his affection for the history, people, and landscapes of the region.

“When I was a kid, I loved the history of America. I happen to think the people who settled the West were some of the strongest, bravest people ever,” Roberts says. “I’ll paint a snow scene, and people will say, ‘Oh, it would be so nice to live back then.’ And I’m going, ‘I like my thermostat!’ To live off the land, you had to be strong people. I try to depict that in my paintings: the strength of these people who could survive in this and make a country out of it — they built America.”

Boom Town Drifters | oil | 30 x 46 inches

Roberts regularly participates in the C.M. Russell Museum’s annual fall auction in Great Falls, Montana, and he is one of 22 members of the Skull Society of Artists, a group of living artists who are selected by the museum because their work celebrates the themes and traditions of the Old West, as Charlie Russell’s once did. “Nature can beat you to death, and I try to depict that in my paintings, but I also try to make them romantic too,” Roberts says. “Cowboys had a tough life, and how warm does that candlelight feel. I want to tell a story and create emotion. I want the viewer to feel something when they look at my paintings.”

Lately, Roberts has particularly enjoyed portraying street scenes, and his early start in sign painting has reappeared in a way he didn’t expect. In the signage above a clapboard building or subtly included in the façade of a barn, he will add a collector’s name or business logo to personalize a commission or giclée. “That’s where the sign painting I was doing back when I was 14 is really tying into what I am doing now in my 60s; it’s all interconnected,” Roberts says.

Trouble In The Pines | oil | 24 x 30 inches

Terry Ray, the owner of the West Lives On Gallery in Jackson Hole, Wyoming, says that Roberts is known for his storytelling ability. “When he first came to us, it was obvious he had talent with Western pieces, and we liked it a lot, and so did our client base,” Ray says. “His art has improved over the years, and so has his national notoriety. He is very well known and very well sought after as a collectible artist.”

Roberts first visited Montana 20 years ago to participate in the C.M. Russell Museum’s auction. In 2007, he and his wife, Nancy, moved to the Bitterroot Valley from their native Texas with their two daughters, Mary and Anna. A typical workday starts early, with Roberts arriving at his studio in Stevensville each morning and returning home in the evening at about 7 p.m. “In the studio, I enjoy the smell of lumber because there’s a frame shop there, too,” he says. The artist works six days a week, resting on Sunday.

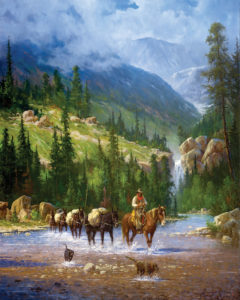

The Outfitter | oil | 24 x 36 inches

While art was his calling from a young age, Roberts admits it’s not the life for everyone. He recalls an explaination he once gave to a reporter after his work sold for greater than its estimate at auction. “An artist gives everything he has, especially at a national level. We put everything we have into that painting, and a museum does all they can to promote it,” Roberts says. “But 20 minutes before the auction, it’s out of your control; it’s in God’s hands. And you feel like you are naked on the corner of a busy intersection. Then when you get your first bid, someone throws you a fig leaf. And then when it sells above its high estimate, you walk away in a robe. Sometimes, it’s not always successful, and you’re looking for a bush to hide behind. That’s the life. This has to be a labor of love, or you will have a long, tough life. There are easier ways to make a living. It must pull at your heartstrings and all of that.”

Based in Bozeman, Montana, Christine Rogel is a freelance writer, the editor in chief of Western Art & Architecture, and the managing editor of Big Sky Journal.

No Comments