01 Aug Round Up: The Montana Modernists

This wave of postwar artists needed to express themselves differently from the Western illustrative work permeating the state. Their experiences, their point of view, and the changing world they found themselves in required something more. As Robert DeWeese noted, “The art students in 1949 were a completely different lot. They’d been in the war all over the world, and they were hungry for all of it.” It is not a leap to suggest that so many veterans who had seen the world, the war, the dropping of the atomic bomb, the devastation of Europe, and the reckoning with fascism needed a new way to communicate.

Johnson, Stockton, Wilber, Senska, and the DeWeeses understood that bringing Modernism to Montana meant they needed to take imagery already in art, the land, and translate that into a more expandable vocabulary that could include a broader context than that supplied by illustrative Western narratives, as told by men.

What holds these artists together is not their style, although all of them trace their lineage to Modernism, especially the work of Paul Cezanne, but rather their philosophy, their attention to the changing aesthetics buzzing throughout the country, and their discussions — political and academic — that would come across on the canvas and in the clay. The late nights, the conversations that lingered like so much smoke drifting across the room, bred a heady atmosphere. These artists shared a philosophical aesthetic clearly at the forefront of Montana at that time. They believed in expressing the essential nature of place and winnowing objects down to the barest minimum needed to voice their perspectives. These artists pushed against Montana’s mythical past to come away with a style of Modernism that offered Montanans a viable alternative to recognize themselves and form their own identity. In order to be a Montanan, a person did not have to bushwhack in the wilderness or wrangle cattle on the open range. A Montanan could embrace an intellectual and academic freedom, love cats, or investigate the political landscape.

Identity is strongly tied to storytelling. Personal narratives, the bombastic style of advertising, media, and historical factors often morph into mythologies. The Montana Modernists began to deconstruct that mythology, which they encountered all around them. It is only by providing a broader context for establishing a narrative that people can begin to understand their place within that story.

The Montana Modernists did that through their art, by providing a fresh canvas on which all Montanans could see themselves portrayed. They translated the experience of living in Montana through patterns, composition, and form. They tossed aside nostalgic imagery and instead related experiences to emotional and tactile responses that occurred in the moment: the notion of home and gardens, the feeling of a blizzard wiping out one’s sense of direction, and the hard work of tending to livestock on a daily basis. They opened up a way for Montanans to see themselves as something other than a mere trope, and they invited women to the conversation for the first time.

Place, education, and community — both individually and considered as a whole — contributed to developing a lasting impact on Montana and a way of seeing that had lasting effects on the struggle for an elastic yet authentic Montana narrative.

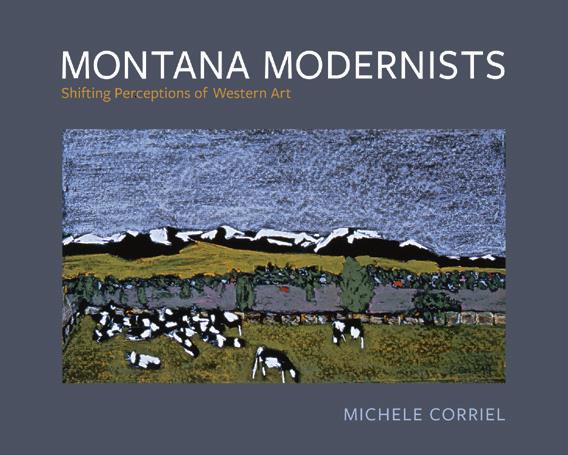

Excerpted from The Montana Modernists: Shifting Perceptions of Western Art (Washington State University Press, fall 2022), which discloses the untold story of art in Montana. Through the work of six artists — Isabelle Johnson, Bill Stockton, Jessie Wilber, Frances Senska, Robert DeWeese, and Gennie DeWeese — Michele Corriel, MA, PhD reveals the historical impact of these artists on contemporary art. Excerpted with permission from Washington State University Press.

No Comments