01 Aug Outside: Sacred Spaces

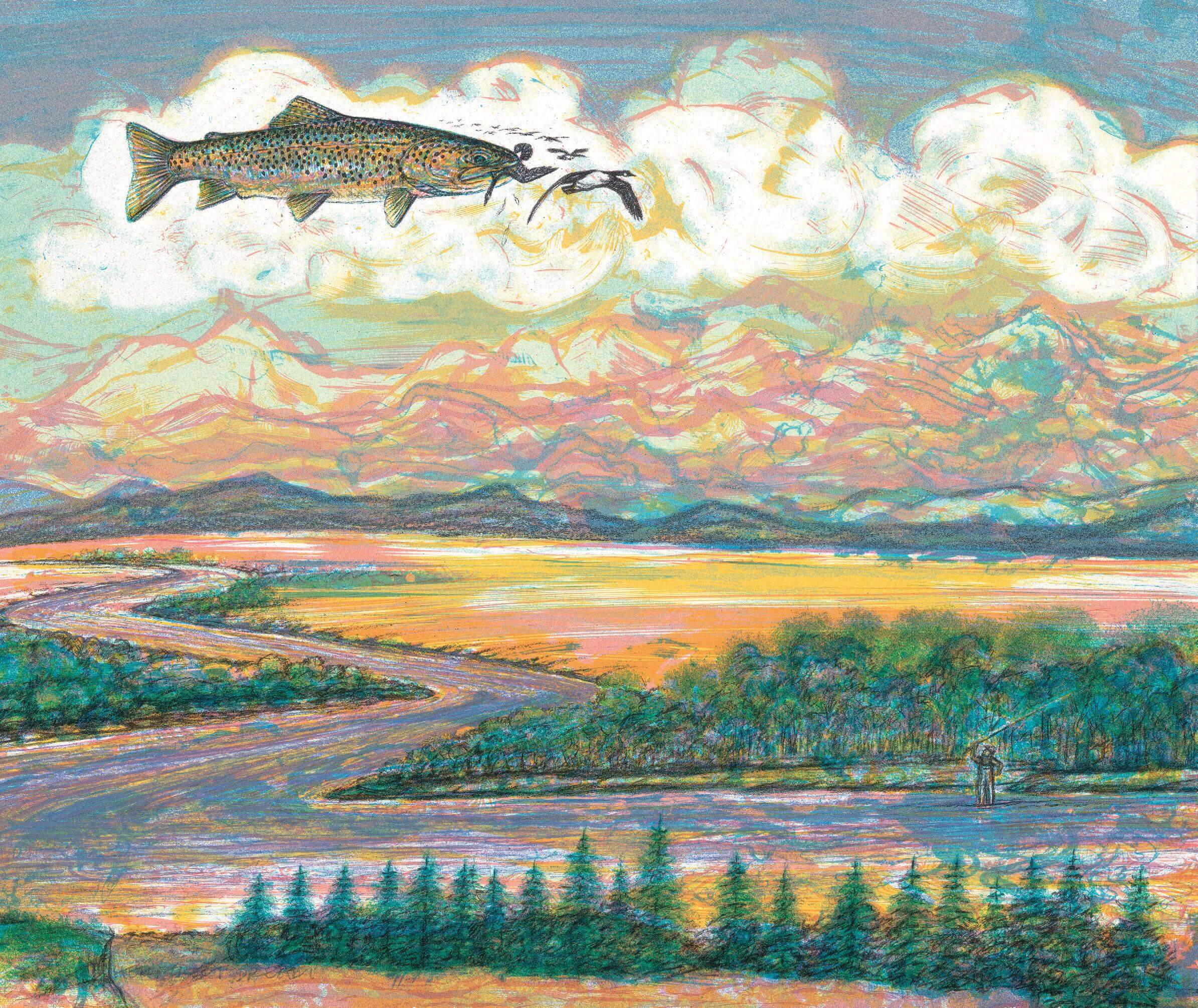

I live in a land of sacred spaces. The Triple Rock sits on the bank of the historic Blackfoot River in northwest Montana, in an area known as the Crown of the Continent, one of the last contiguous untamed landscapes in the U.S. There, nature’s melange of wildlife, mountains, rivers, and sky all blend into one magnificent landscape. I live in a log cabin overlooking the river, nestled between the Garnets to the south and Game Ridge to the north.

The Blackfoot River is known for its pristine, gin-clear waters and wild trout: bulls, cutthroats, rainbows, and browns. Fed by natural springs and melting snow on the west side of the Continental Divide, the river runs cold and fast, rushing downhill over more than 132 miles of gravel beds, cobbles, and massive boulders. It’s no wonder these waters are revered by fly anglers worldwide.

Beside our cabin is a regal stand of ponderosa pines and Douglas firs, surrounded by clusters of low-lying bearberry and larkspur. The cool shade of the green canopy opens into golden meadows strewn with silver sagebrush, stonecrop, and more than 200 species of native grasses and wildflowers. Beguiling names like owl clover and rosy pussytoes, Indian paintbrush, and fuzzy tongue penstemon evoke images and textures that are beyond beautiful. Pink bell-shaped crowns of kinnikinnick intermingle with native sedges and tufts of bluestem. Thousands of rocks left by melting glaciers lie scattered across the wide expanse of grasslands covering the valley floor as far as the eye can see. I can feel — almost hear — the hum of the Underland.

The Blackfoot Valley is hallowed ground, its story still unfolding through a rich oral and written history dating back a millennium, when Salish and Kootenai tribes followed the Kokalahishkit Trail to their summer bison hunting grounds. Merriweather Lewis walked the valley in 1806 on his return trip to rejoin his partner William Clark on the east side of the Continental Divide. Norman Maclean’s novella A River Runs Through It, written more than a century later, is based on the author’s personal experiences growing up around and fishing the Blackfoot River. It is truly an iconic place.

In the spring, if you catch the mid-morning sun just after it climbs over Morrison Peak, you can see the faint indentation of Native American travois marks in the front pasture. Three ancient stone cairns sheathed in muted shades of yellow and orange lichen rest upon a slight rise, still beckoning weary souls to the river’s edge.

Our cabin sits in solitude on a grassy bench atop a steep granite ledge overlooking the river. It’s a secluded spot, hidden from view by mature larch and cottonwoods, interspersed with scrubby junipers and red-osier dogwood that share the sandy bank below us. We have few neighbors, and most are the four-footed kind who prefer a solitary lifestyle: grizzly bears, wolves, mountain lions, elk, moose, and fox, to name a few. Some are predators, some prey, but all are keepers of this pastoral valley that sustains us.

Mornings at the Triple Rock are exhilarating; waking up to the sounds of the Big Blackfoot River as it splashes its way downstream, slapping at the massive multi-colored boulders rising above the surface of the water, is like nothing else I’ve known. The air is alive with the raucous cackle of bald eagles, osprey, and red-tailed hawks. Kestrels skim the valley floor, hunting for field mice and grasshoppers.

I often stand at our front gate, leaning against the peeling green, weathered railing, and watch clouds, sometimes for hours, tumble over Sheep Mountain into the west end of the valley. Clouds in all variations of shapes and sizes drift one after another against a cerulean sky, stacked tightly like the sterling silver teaspoons in my mother’s antique chest.

Evenings are captivating too, watching the nighthawks’ spectacular aerial shows, listening to the whirr of their vibrating wings as they plummet toward the valley floor before abruptly shifting into a horizontal glide. A gaggle of geese flies over, honking and squawking. Ravens chatter noisily as they return to their nocturnal roost across the river. I am in good company.

In the summer, visitors driving down our road are usually fly anglers and their guides, who often travel a great distance to wet a line in one of the most celebrated trout waters in Montana. Now and then we exchange greetings at the river’s edge, and pleasantries often lead to questions and comments about fish. Have you seen any trout rising? What insects have you seen? We’re here for the salmon fly hatch. Sometimes, as if on cue, a bald eagle will glide past and we stop to watch, mesmerized by its remarkable wingspan.

But anglers become more scarce as winter approaches. Trout settle deep in the river, some burrow securely into glacial gravel beds, others rest in deep dark pools beneath overhanging ancient mudstone shelves. The forest floor is peaty with decaying undergrowth and caches of damp shredded pine cones, leaving saffron and amaranth smudges of color.

Winters are frigid in these parts. Temperatures can drop into single digits for weeks at a time, with occasional minus-40 degree days and a cold so bitter that it’s literally breathtaking. Once-golden meadows lay dormant beneath the snowpack, and biting gale-force winds strip the valley of its foliage and texture.

The tamaracks, celebrated in the fall for their brilliant splashes of crimson gold, lose all trace of color and fade to sepia. Twisted gray junipers, stacked at the river’s edge, appear soot-black against the chalk-white backdrop of the snowy hillsides. The silence is profound, and a quiet calm blankets the valley.

Yet, it’s still magical. Fences and tree branches sparkle with hoarfrost. Tiny ice crystals twinkle as they spin and pirouette in the sunlight, streaming through the frozen air. In the fast-moving waters beneath the surface of the river, anchor ice clings to the rocks on the bottom, its turquoise color appearing strangely tropical.

The county snowplow clears the 4-mile stretch of road past our front gate. Beyond that, it’s impassable until the spring thaw. Our road can be dangerous and unpredictable in a snowstorm. Rarely does a visitor stop by on a whim. I often walk our road at dusk, watching the last blush of alpenglow linger on the ridgeline. The stars are brilliant, illuminating a night sky dominated by the Milky Way and occasional northern lights.

Standing in the middle of the road, in the last remaining moments of twilight, I often hear the muffled hoot of a great-horned owl. I open the gate and turn toward home, already anticipating the first hint of dawn and the promise of another day in this most sacred of places.

Deborah Houlihan O’Connell is a freelance writer whose essays and poetry are inspired by our inherent connection to nature and the wildlife and landscape that surrounds us. She lives with her husband, Jerry, and two dogs on the banks of the Blackfoot River in western Montana. When she isn’t writing, she’s out walking in the wilderness.

No Comments