22 Aug Yellowstone Traditions: A Quite Revolution

Harry Howard has been summoned from his office at the headquarters of Yellowstone Traditions, a construction company whose work could belong to craftsmen centuries past.

A doorknob turns somewhere down the hall, followed by the sound of shoes clacking across a floor of reclaimed bricks.

In the waiting area, a few chairs mill about a coffee table that’s stacked with home magazines, undoubtedly containing volumes of YT’s work. Nearby, a fast-looking road bike leans against the front desk.

The clacking grows louder, sounding strange. Each footfall delivers one click, instead of the heel-toe double you’d expect from a stiff-soled Italian leather loafer.

Harry rounds the corner in shorts that look equally comfortable on a desk chair or a bicycle seat. It’s the metal cleat on the ball of each foot that does the clacking. When his shoes aren’t rapping against the floor, they’re snapping into his road bike’s clipless pedals.

He rides to work most days in the summer and dresses quite casually — even by Bozeman’s standards — for a leader of a company that caters to those investing passionately in structures of limitless beauty. But there’s something soothing about him, about his confidence in his own ways and in the ability of the company to create precisely what their clients seek.

Harry, in his 50s, was raised in New Jersey on the Hudson, looking out over New York City.

“I knew I didn’t belong there,” he says.

His family had a farm and lake cottage in Quebec, where he spent summers exploring pastures and woods and very old buildings.

After high school, he worked a year for a French Canadian, doing everything from tapping trees and making maple syrup to deconstructing old barns and out buildings to sell piecemeal. That’s where he fell in love with the aesthetic of place, and of that which embodies the old, analog thingliness that can only be wrought by time, by thought and by hard-ridden hands.

Shortly thereafter, he headed west, and at the age of 25 he came to Montana. Almost immediately, he began restacking and restoring turn-of-the-century log buildings.

“I got really disappointed with how the West was getting developed. There was no regard for history,” he says. “My desire was to contribute something different, something in tune with the landscape and the history of those who’d come before.”

Harry partnered with the founders of Yellowstone Log Restoration and began building original structures from reclaimed materials. And so Yellowstone Traditions was born. They hired subcontractors, craftsmen and project managers, jobsite supervisors and accountants, and eventually expanded to own their own materials yard and cabinet shop.

Today, YT is run by owners Harry Howard, Ron Adams, Justin Bowland and JoLin Freman and employs 45 people. In the 25 years intervening, the company has completed 400 or so building projects.

Sure, plenty of construction companies build more than 400 homes in one year, but Harry says YT is unlike any other builder. He may be right. Only six of YT’s buildings have changed hands since 1986.

“These are not short-term ventures,” Harry says. “These are generational projects, and we’ve become deep, long-term friends with just about every one of our clients.”

With history as their guide, YT hasn’t had much to do with housing developments. You won’t see most of their work from any public road, and it’s not unusual for the nearest named town to lie more than 40 miles away.

They specialize in remote ranches and recreational properties, where sometimes there’s no electricity to the area. In that case, they’ll utilize alternative energy systems during construction, which later power the home.

And these properties aren’t just remote, they tend to be expansive. Their 400 projects sit on more than 2 million acres — more landmass than the entire state of Connecticut.

“Many of these have been tired properties that our clients had the resources to restore the streams and the vegetation and the habitat — probably better than the national parks. It’s a strange, quiet revolution,” Harry says.

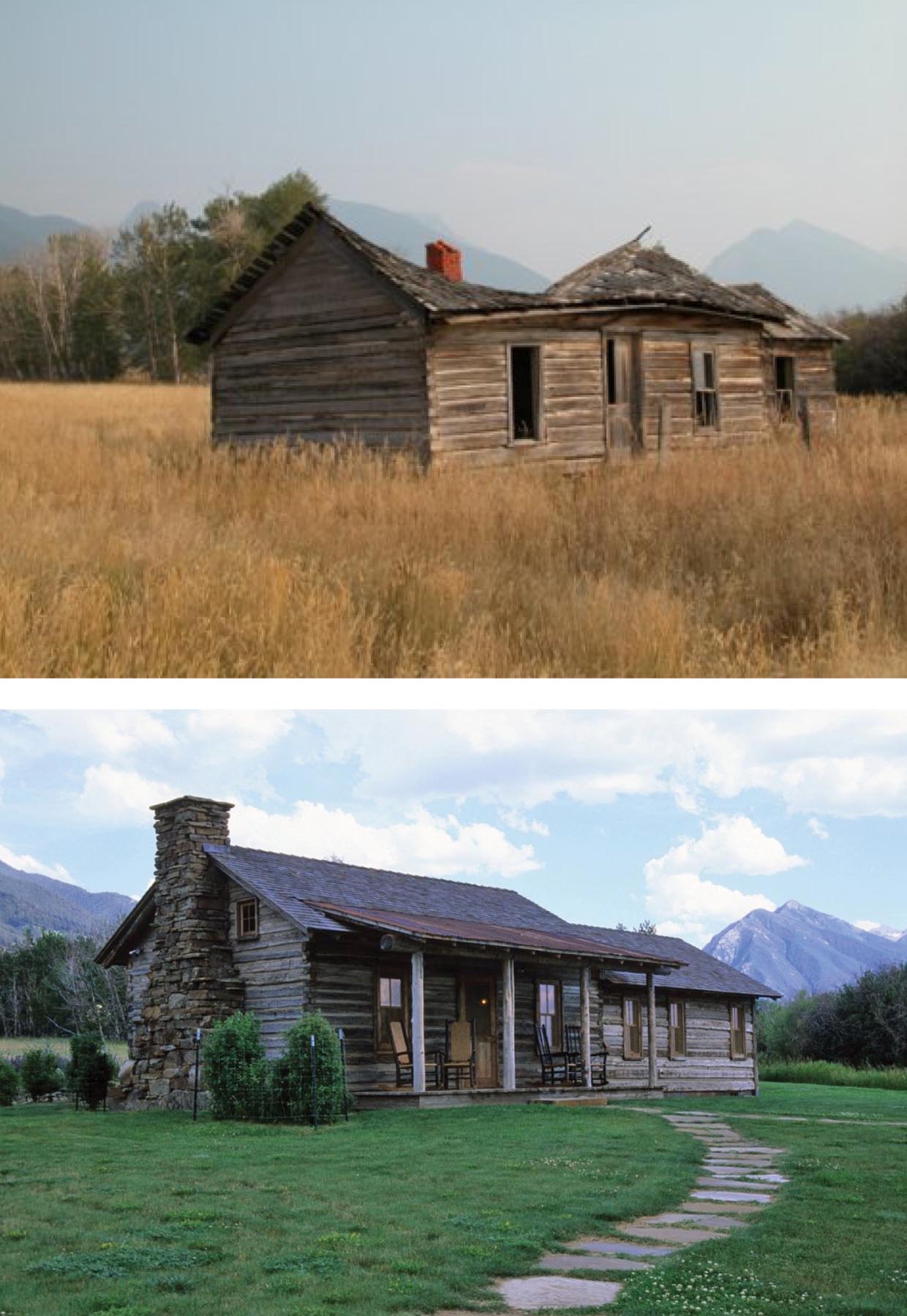

Revolution, or perhaps reformation, best describes what YT has been up to. They’ve played a key role in popularizing reclaimed and found materials, giving the West an identity rooted in its hardscrabble history.

“Once upon a time, people had more time than money, and old structures reflect that,” Harry says. “Our structures reflect that.”

But that doesn’t mean they don’t know how to invent. Their innovative finishes seem to look backward and forward all at once, from floors of thick cowhides stitched together in tessellation to 300-year-old Spanish colonial doors to wavy mesquite wood flooring, where each board is scribed to precisely fit the one beside it.

And YT’s structures span just about every conceivable size and cost, from a 400-square-foot chicken-coop-turned-guest-cabin where the owners labored alongside the construction crew to a lavish 30,000-square-foot home to a functional 70,000-foot-arena.

YT’s body of work has left an indelible mark on the way we now build in the West, and they have been the guiding visionary behind it all.

“This work has been the joy of my life — raising my family and raising this company, which is like family. What a joy it’s been,” he says.

- YT worked with Miller Architects on this sub-alpine home that overlooks one of Montana’s pristine mountain valleys. YT’s craftsmen integrated a palette of bark on cedar logs, antique hand hewn beams and reclaimed siding in finite detailing on both the interior and exterior of the home.

No Comments