23 Jul Books: Writing the West (Winter 2011)

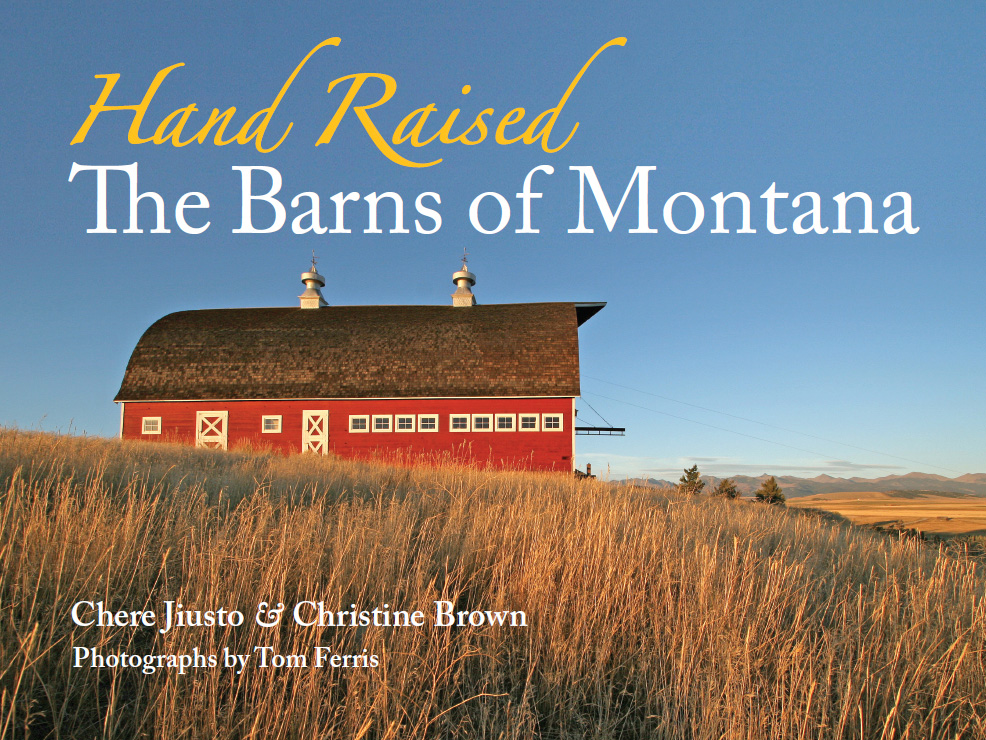

Hand Raised: The Barns of Montana

This comprehensive history and photo essay of historic barns featured in Hand Raised: The Barns of Montana (Montana Historical Society Press; $39.95) is as much a tome to the hardworking people of Big Sky Country as it is a showcase of regional architecture. In this book, with its intriguing color photos of 140 different structures, photographer Tom Ferris captures the practical and romantic essence of barns along the landscape.

Alongside the photos, authors Chere Jiusto and Christine W. Brown do great justice to the legacy of the barn, by wrapping detailed research into these buildings and highlighting foremost the people who keep more than the structures standing, but who are dedicated to a way of life. From the elegant 1885 J.C. Adams stone barn in Missouri River country to the humble hand-hewn, chinked log sheds of the Dewey Twin barns, circa 1877, of Beaverhead County, the stories layered into these buildings bring depth to the book.

More than a nostalgic notion, Hand Raised: The Barns of Montana, offers a call to action. As our culture shifts from small farm to a global model, the old barns are vanishing at a rapid rate. The last chapter, “Preserving the Legacy”, is a quiet call to action. The authors suggest a new kind of barn raising, one that encompasses reusing or moving the structures to repurpose them as public buildings, museums or even homes.

Geology Underfoot in Yellowstone Country

Geology Underfoot in Yellowstone Country (Mountain Press Publishing; $24), by Marc S. Hendrix, states in the first line of the preface that it’s “designed to be an easy-to-understand introduction to the geology and geologic history of Yellowstone Country.” This meant two potential things to me: 1) That it might be a dry read; and 2) That the book might also be tailor-made for me, someone who doesn’t know schist from shale.

Turns out I was wrong on the first count and right on the second. The book is a highly readable guide that explains all that complex geology-speak in layman’s terms without speaking down to the reader. I never once came close to nodding off while reading this book, and as a bonus I learned a boatload about the unique geologic region that is Yellowstone Country. The author takes readers to more than 20 sites in the region that illuminate its geologic history, from hundreds of millions of years ago when it was a seafloor (!) to its current status as a hotbed of hot springs and raw mountains.

The softcover, 302-page book (on rugged paper stock for lugging in the field) is generously filled with GPS waypoints, color illustrations and maps (66), and color photographs (115), all accompanied with detailed captions that serve the page-flipper well. Readers of Geology Underfoot in Yellowstone Country are in good hands: the author is a geology professor at University of Montana at Missoula, and has traveled the world pursuing geological and geophysical information. So nodding off is not an option.

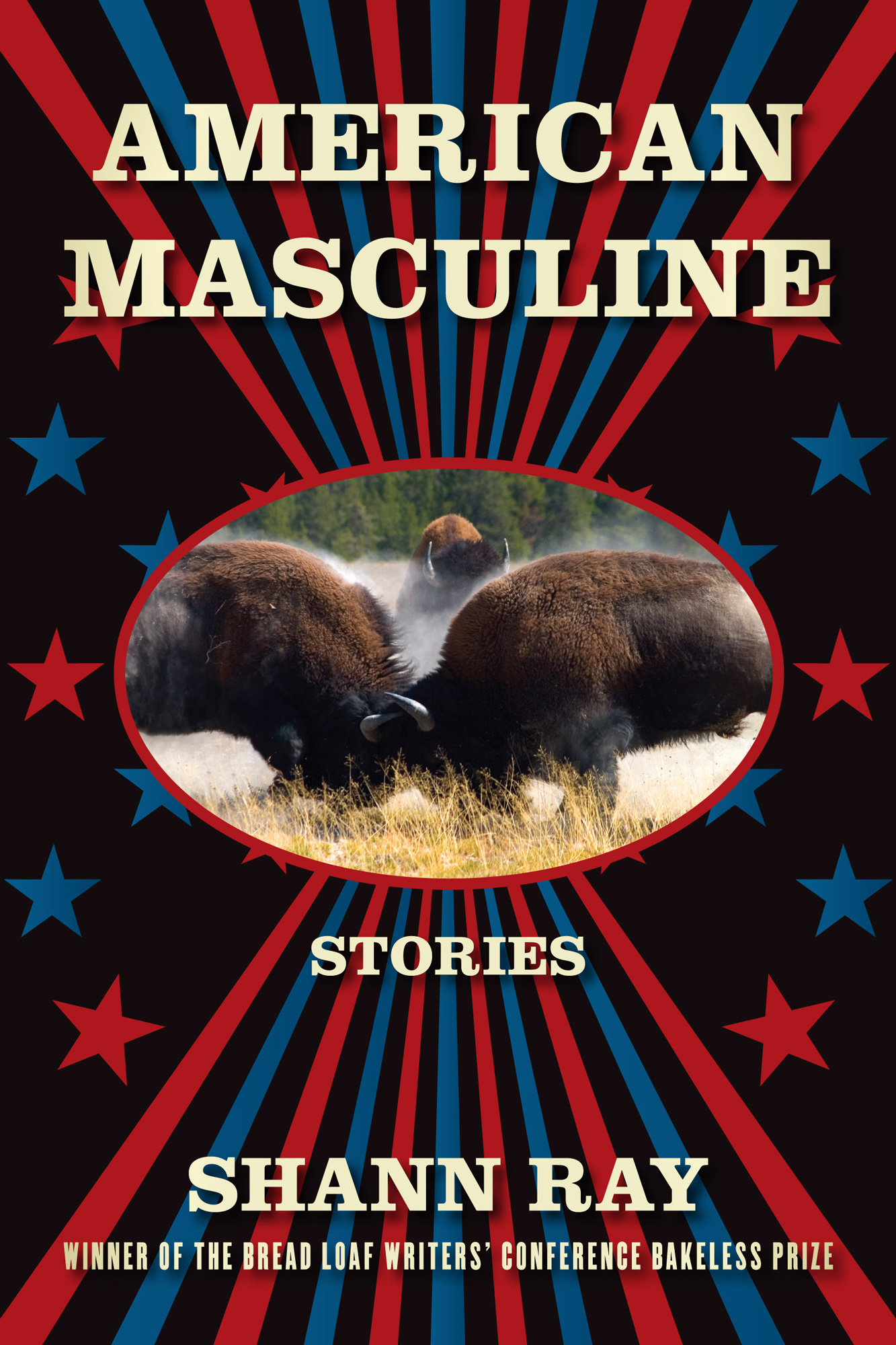

American Masculine

Author Shann Ray’s American Masculine (Graywolf Press; $15) is a boldly written collection of 10 multi-layered stories, no light fare here. These tales offer readers cold, cleaving blows of violence in which characters reveal their base selves, animal and pure, often unhealthy. These moments are braided with sharp instances of reflection that earn characters some scrap of personal insight or full-blown revelation. Set in the contemporary and historic West, social mores more so than the physical landscape shape the players and serve as a fitting backdrop for the emotional drama that unspools in the stories.

Each careful sentence is all absorbing and brims with sudden poetry that pauses the reader, then forces a reread to experience the wonder of Ray’s finely wrought words: “In her hand he finds a page torn from scripture, Isaiah in her fingers of bone, the hollow of her hand, the place that was home to the shape of his face.”

These stories read like parables, and as with the best of such tales, the reader comes away bothered, discomfited by the raw emotion therein, like a sliver wedged under a fingernail. It will work itself out over time, but until then it will let you know it’s there, demanding attention and hurting like hell.

Raptors of the West: Captured in Photographs

The artful new book, Raptors of the West: Captured in Photographs (Mountain Press; $30) is shot and presented by a trio of raptor enthusiasts and photographers. Kate Davis (founder of the nonprofit Raptors of the Rockies) and award-winning photographers Rob Palmer and Nick Dunlop collaborated on this new book that showcases, as the title promises, the full range of raptor birds that wheel the skies of the western U.S., from California condors to bald eagles to American kestrels to diminutive elf owls and more. They are arranged by habitat type and breeding-season region, but this glossy 240-page collection’s real strength resides in more than 400 full-color crisp, mesmerizing photographs and extended captions loaded with information.

For instance, did you know that a gyrfalcon nest in Greenland has been used continuously for 2,500 years? That peregrines’ diving speeds may top 220 miles per hour? That Swainson’s hawks migrate from North America to Argentina — a one-way trip of 6,200 miles? That 40 years ago, in the 1970s, only 12 bald eagle nests could be found in Montana, but today number 400 pairs? That in a 10-year lifespan, a single barn owl can eat roughly 11,000 mice (for free, and far less harmful than pesticides)?

The photographs, up-close and with stunning clarity, sing with tension, with the savage beauty of mid-air battles, with tender moments of fledgling owls frolicking, and lone falcons attacking flocks of starlings numbering in the tens of thousands.

Deserving hours of attention, Raptors of the West is an educational and visual feast that should sit on every home coffee table and schoolroom bookshelf.

The Fragrance of Grass

In his new memoir, The Fragrance of Grass (Lyons Press; $24.95), we learn that though Guy de la Valdene has led a privileged life, he has not been idle. In the prologue, he states: “I have hunted at least one hour a day for three months a year, ever since I was 8 years old. That translates into more than 5,000 hours in the field. … I can safely assume that I have had my hands on the stock of a gun for one whole year of the 65 that I have been around. I like to walk, and I know guns.”

Add to this lifetime of field experience a passion for birds (notably partridge), for dogs, for the outdoors, for fine women and fine food, then stir in formidable writing ability and a penchant for rumination, and you have an entertaining, informative book that is difficult to put down — and one that will appeal to a far wider audience than might be suspected. From his earliest days as a lucky youth growing up in a castle in France (complete with moat, servants, and a BB gun), through a lifetime of excessive kills (by his own estimation), de la Valdene recounts episodes that punctuate his lifelong quest to pursue game with a gun. The recurring theme that he has killed more than his share of game seems at odds with the life of a lover of the hunt, yet he explains it with poetic honesty: “ … instead of hunting with the purpose of killing, I now enter nature’s domain as I would enter the territory of dreams.”

The Fragrance of Grass takes its title from a slice of poetry by his chum, writer Jim Harrison: “Between the four pads of a dog’s foot, the fragrance of grass.” Most appropriate, as the book becomes especially poignant and humorous where his dogs are concerned: “Labs are the women to talk to on car trips, and pull under the blanket at ball games, dogs whose devotions are equally divided between their master and the food they are offered. Bird dogs are the crazy bitches who keep you up all night, begging for more.”

Despite relating a lifetime of memorable moments acquired in the fields, dining rooms, and blinds throughout Europe and North America, The Fragrance of Grass is really about a sportsman entering his later years with thoughtful, albeit conflicted, ease. De la Valdene now relishes a serene enjoyment of his 800-acre farm in Florida, where he walks daily to escape the invasive creep of modern life: “Of all the sounds that touch my soul these days, the most beautiful one of all is silence.”

The Shootist

Glendon Swarthout’s recently reissued 1975 novel, The Shootist (University of Nebraska Press; $16.95), may largely be remembered for the John Wayne film made of it (the screenplay of which was written by the author’s writer son, Miles Swarthout). But the book deserves the attention of this reissue, at the very least because it is a hell of a novel.

The writing is rich with period detail, pinning like a moth to a collector’s board that dusty but hopeful time when the Old West died and the young West was born, the old century acceding to the new. Swarthout plays this theme expertly, likening Queen Victoria’s recent passing with the title character J.B. Books’ imminent passing, two tough characters who have no place in the 20th century. In Books’ words, “Maybe we did outlive our time, maybe the both of us did belong in a museum — but we hung onto our pride, we never sold our guns, and they will tell the two of us that we went out in style.”

This new edition, a handsome oversize paperback, is prefaced with an entertaining introduction by Miles Swarthout in which he details his father’s novel, from idea to publication, from screenplay to screen. It’s filled with insights about John Wayne and the making of the Duke’s last film, a process chock full of irony, as the protagonist and the movie star, the historic Old West and the Old West of Hollywood — icons all — were going about the hard task of dying away. (It would be Wayne’s last film.)

Readers familiar with the movie should not make the mistake of skipping this novel. It is not only surprisingly different than its big-screen sibling, it is a prime example of first-rate storytelling and more than deserving of renewed attentions.

Swarthout’s description and use of language render The Shootist poignant and poetic, and, given its weighty subject matter, curiously uplifting: “The day was buoyant. A ship of tropic air had voyaged inland from the Gulf of Mexico with a freight of spices, and this day on the desert was informed with a balm and sensuality that made him long to cry out, not with pain but with delight.”

Blue Heaven

Willard Wyman’s Blue Heaven (University of Oklahoma Press; $21.95) is a fine follow-up to his award-winning 2005 novel, High Country. Though chronologically Blue Heaven is a prequel to that book, one need not read this first to enjoy the other (but you’ll want to). As with the previous book, on its surface Blue Heaven is a tale about a mule packer in the high country of Montana, but of course it is so much more than that.

Somewhat picaresque in its construction, the book traces protagonist Fenton Pardee’s spiritual and emotional maturation from its 1902 opening with a train wreck that portends much and ripples throughout the rest of the story. From the start, Pardee is nearly a man in full: He is possessed of an enviable certainty of character and conviction of his passions, even as he learns what they are throughout his life.

There is a subtle but powerful wryness to Wyman’s writing, reflective of Pardee’s demeanor, as when struggling with jerky offered by a friend while ruminating on why his horse died: “ ‘This jerky of yours,’ Fenton added, continuing to chew, ‘might give whatever killed her a good run for its money.’ ”

Love is a deeply probed topic in these pages — the emotional bonds between people, Pardee’s love of nature, the mountains that he spends a lifetime exploring, worrying about, and ruminating on and in, love of a way life repeatedly threatened by the inevitable encroachment of the modern world. The band of people in this small community not far from Missoula are more like family to each other than mere acquaintances. The author’s depictions of them as poking, prodding locals sometimes too much in each other’s lives never trends into farce.

Blue Heaven is a book to be savored as much for these engaging characters and side-tracks the story takes as for the sudden wry observations Pardee makes, rich and demanding of consideration by the reader. At times he comes across as almost too aloof and philosophical, but then the reader realizes, along with Pardee, that he is just a man learning and growing even as he and his loved ones age and succumb to the demands of an always-changing world, the alterations of trusted times and friendships, as with the end of this rich book, coming too soon.

(The book’s only flaw is not with Wyman’s award-worthy writing and storytelling skills, but with the multiple typographical errors a decent proofreader should have caught.)

No Comments