23 Jul Books: Writing the West (Winter 2009)

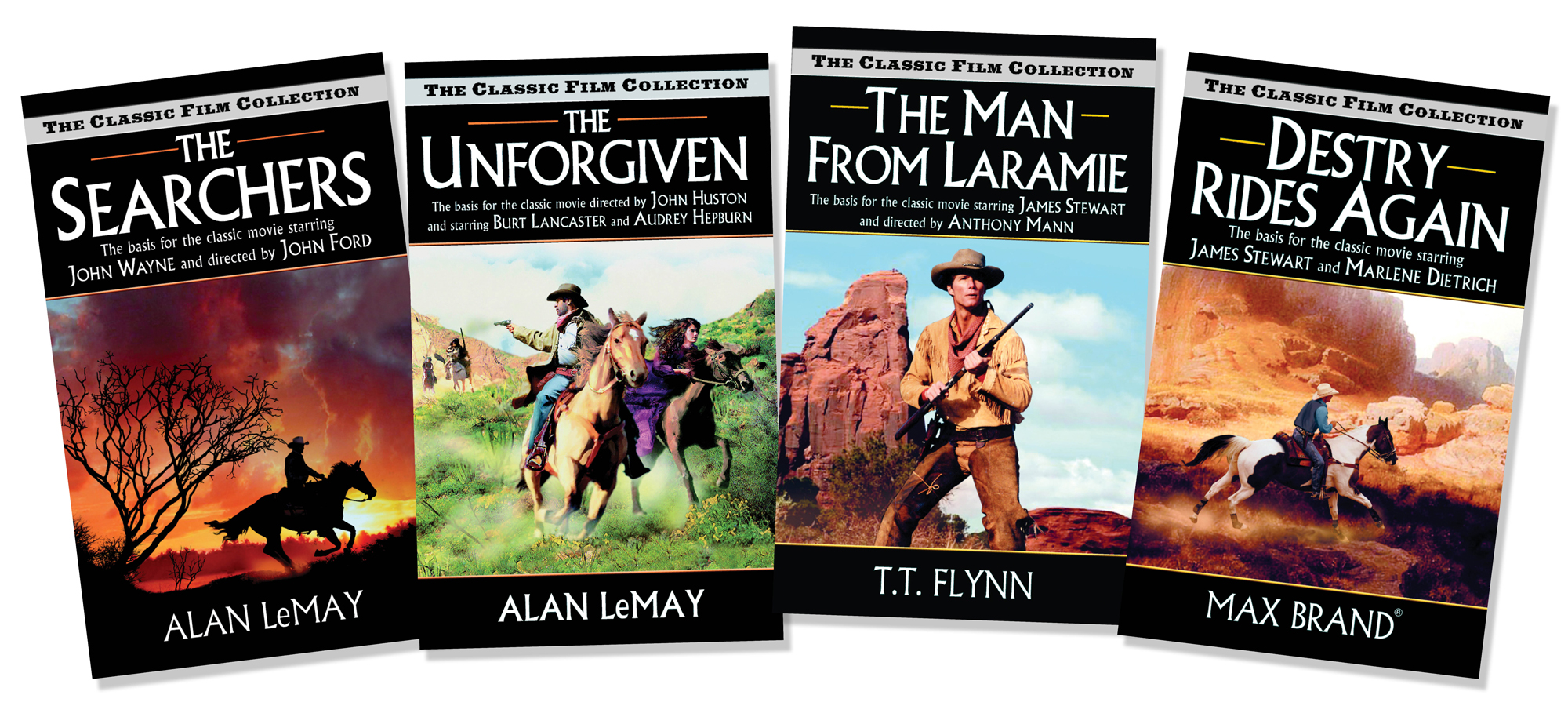

Classic Film Collection

In these high-tech, ricochet-speed days, a distinctive concept goes a long way in the publishing world, and the good folks at Dorchester Books have hit on a doozy: They’re reissuing classic Western novels that were at one time made into classic Hollywood films — hence the series’ name: The Classic Film Collection (Dorchester Publishing, $6.99).

Four novels were chosen as the inaugural offerings: The Man from Laramie by TT Flynn and Destry Rides Again by Max Brand, were each the basis for the now-classic Western films starring James Stewart. The other two novels, both by Alan LeMay, are The Searchers, which became the 1956 film with John Wayne (a film which Wayne considered his finest performance, by the way), and the last, The Unforgiven, the basis for the 1960 film starring Burt Lancaster and Audrey Hepburn (not the unrelated 1992 Clint Eastwood flick, Unforgiven).

Some potential readers will wonder why they should read the books if they’ve seen the films. Fair point, but the reasons for reading these classics are many. In the case of Flynn’s The Man from Laramie, a fistful of superlatives might do the convincing: When it was originally published in 1954, more than a half-million copies were in print. The film, starring James Stewart and directed by Anthony Mann, is credited with being instrumental in changing the way Americans viewed the Western. No longer was it a white hat/black hat world, but rather a sometimes dark place with morally complex themes. And now the book is back in print for the first time in 50 years.

At times these books, as with so many from which popular movies are made, share the thinnest of plot points with their celluloid counterparts, as with Brand’s Destry Rides Again, though both the book and the movie are well regarded. Such was not the case with the two films based on LeMay’s novels, which were faithful to the books nearly throughout, though the ending of the film version of The Searchers thunders off-trail enough that a reader may consider if the filmmaker, in this case the inimitable John Ford, was correct in his choice of ending for his famous film.

But the real reasons for reading LeMay’s work are for his historic accuracy, his rich descriptions and striking dialogue, and tightly woven plots by a master writer at the peak of his skills. Actually, the same can be said for the other authors here. Their long reputations for telling ripping adventures set in the Old West are well earned.

The books share a distinctive and unifying look, black with silver type surrounding full-color artwork, and though handsome, they are meant for reading. They are standard paperback size, offer an enhanced font that is easy on the eyes, and each book is priced at an acceptable $6.99. As a writer of Western fiction myself, I appreciate Dorchester’s continued dedication to the Western genre. Time and again media pundits have sounded the death knell for the genre, only to be proven incorrect as Western books — and movies (in fact, Hollywood has announced a handful of new Westerns in the coming year) — continue to maintain a solid audience of new and old readers, despite the fact that the heyday of paperback Western fiction (and film) peaked a few decades ago.

Dorchester is planning a March 2010 release for the second quartet in its Classic Film Collection. Here’s a heads-up: The Outlaw Josey Wales by Forrest Carter; Blood on the Moon by Luke Short; The Stalking Moon by TRC Olsen; and The Tall Men by Will Henry. The average fan of Westerns will have read one or two of these titles, but so long ago that a revisit will be well worth the time spent. And if it’s been a while since a book fan has considered picking up a Western… I’m here to tell ya, these ain’t yer grandpa’s oaters, but solid literary efforts that won’t fail to engage and entertain ’til the cows come home. Saddle up!

Bunkhouse Built

The cover of Bunkhouse Built, a Guide to Making Your Own Cowboy Gear, by Leif Videen (Mountain Press, $15), is light brown and has the look of hand-tooled leather — very cowboy. But the real treat is inside: chapter after chapter of practical, hands-on advice and detailed instruction on building and repairing cowboy gear, from hobbles to kerchief slides to halters, and all accompanied with step-by-step instructions.

In his introduction, the author calls the book “a well-rounded guide on putting together your own outfit.” Videen knows of what he speaks — he’s a working cowboy who “spends much of the year in remote mountain cow camps.”

Galloping in at a tight 128 pages, Bunkhouse Built sports folksy, heartfelt illustrations by the author and a fun — if a tad distracting — non-standard typeface. Detailed descriptions of tasks vital to the working cowboy: sewing, lacing, knot tying, tying a hitch, picketing a horse, and more are followed with a glossary of handy cowboyin’ terms.

For someone like myself who admires the “cowboyin’” way of life (but will probably never live it), I found the processes fascinating and informative. And if I were to take to the trail, I’d no doubt also find the book useful, too. Just in case, I’m ready for volumes two, three and four.

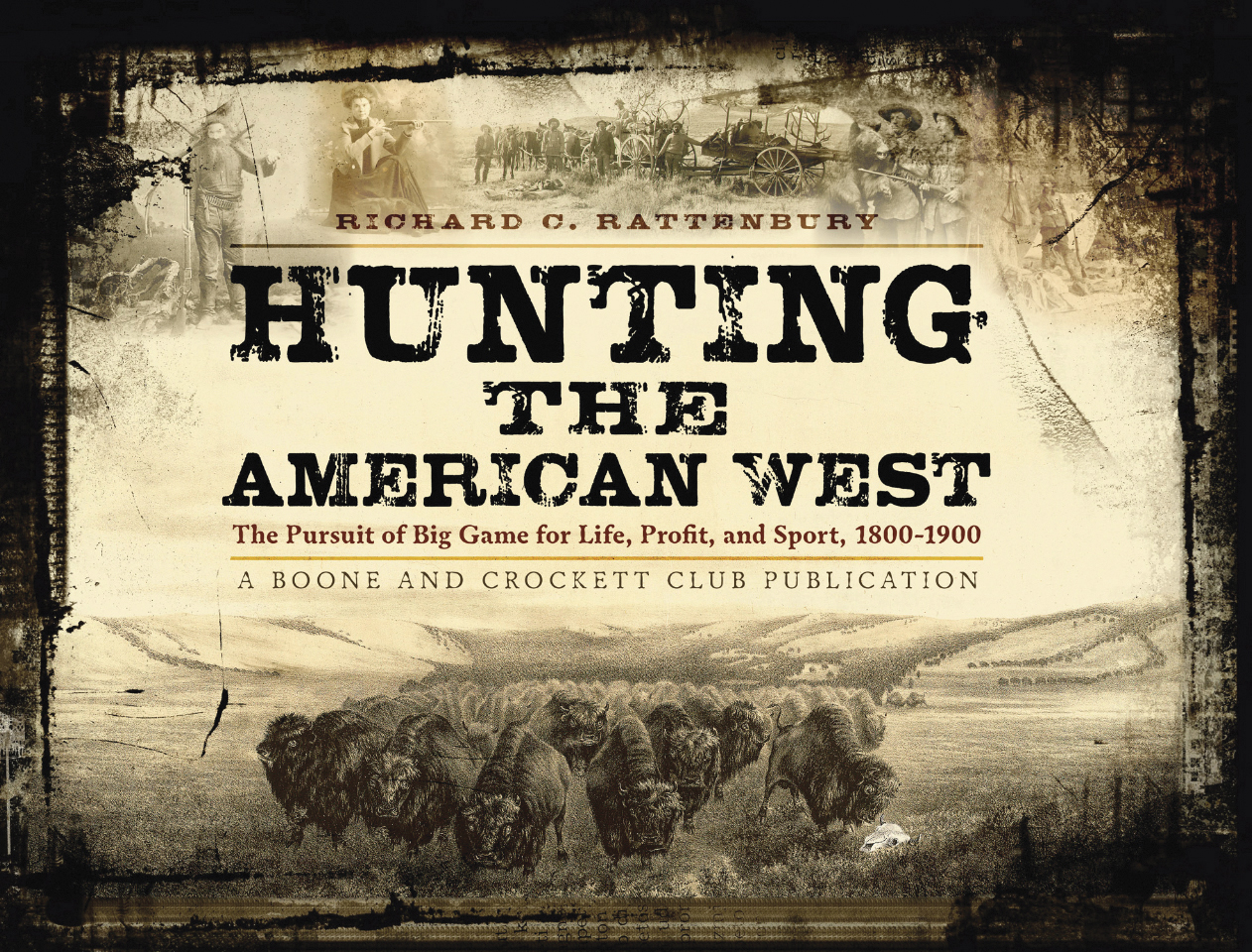

Hunting the American West

In style, in topic, and in size, Hunting the American West: The Pursuit of Big Game for Life, Profit, and Sport, 1800-1900 (Boone and Crockett Club, $49.95), by Richard C. Rattenbury, is a substantial undertaking by any measurement. The scholarly work encompasses the entirety of the pivotal 19th century and manages to be both a visual treat and a well-researched historical text that gathers in one convenient and handsome book all the overarching elements of the enormous topic of 19th century hunting in the American West.

As the Boone and Crockett Club’s director of publications, Julie Houk, says of hunting in the 19th century American West, “It was a period in which hunting evolved from a subsistence activity to a sport of aristocrats to market-driven devastation of our wildlife resources. It’s a saga that ultimately led to the rise of the hunter-conservation movement and the founding of the Boone and Crockett Club.”

Rattenbury explains how until mid-century, the big-game animals of the West were so abundant that, “with the obvious exception of sub-Saharan Africa, the diversity and magnitude of the West’s wildlife populations were rivaled nowhere else in the world. Such an abundant natural resource was bound to be exploited.” And exploited it was, for as much as it is a celebration of hunting in all its various forms and reasons, the author doesn’t shy away from focusing on the devastation of wild populations and the often permanent harm inflicted on them, and the subsequent negative effects caused by white European settlers.

The scope of its ambition notwithstanding, Hunting the American West is a sumptuous 400-page tome on thick, glossy stock. It offers readers lush color reproductions of Western artwork by such masters as Russell, Goodwin, Bodmer and Wyeth, plus hundreds of vintage illustrations, Native American artwork, and vintage and new photographs, each accompanied with an extended caption that offers new information instead of reworking text pulled from the chapters. Hunting the American West is a class act from front to back and is the rare book that will appeal to a variety of readers from sportsmen to history buffs, art fans, casual browsers, and conservationists.

Longhorns and Outlaws

In Longhorns and Outlaws by Linda Aksomitis (Coteau Books, $8.95), the year is 1901 and the age of the great Western cattle drives is well past its apex. Young Lucas Vogel, orphaned by the Galveston Hurricane the previous year, is forced on a Montana cattle drive with his only living relation, his cowboy brother, Gil. These begrudging partners embark unwittingly on a quest that will change them each in more ways than they could imagine.

Bookish by nature, Lucas resents the trail his brother chose for them. But when he discovers they are dogged by what he believes are real-life outlaws, the very type of men he’s obsessed with reading about, he can’t convince the other cowboys of the imminent danger. From here, the book heats up like campfire coffee in a chipped pot.

Though Longhorns and Outlaws is intended for young adults, full-grown trailhands will find its 185 well-written, snugly plotted pages entertaining and rich with history. Included in the book is a glossary of cowboy lingo and Dutch and French words; a note from the author attesting to the historical veracity of the book; and a solid list of other books suggested for further reading. And Longhorns and Outlaws is only the beginning … Aksomitis is planning an “Outlaw” series, with Kidnapped by Outlaws up next.

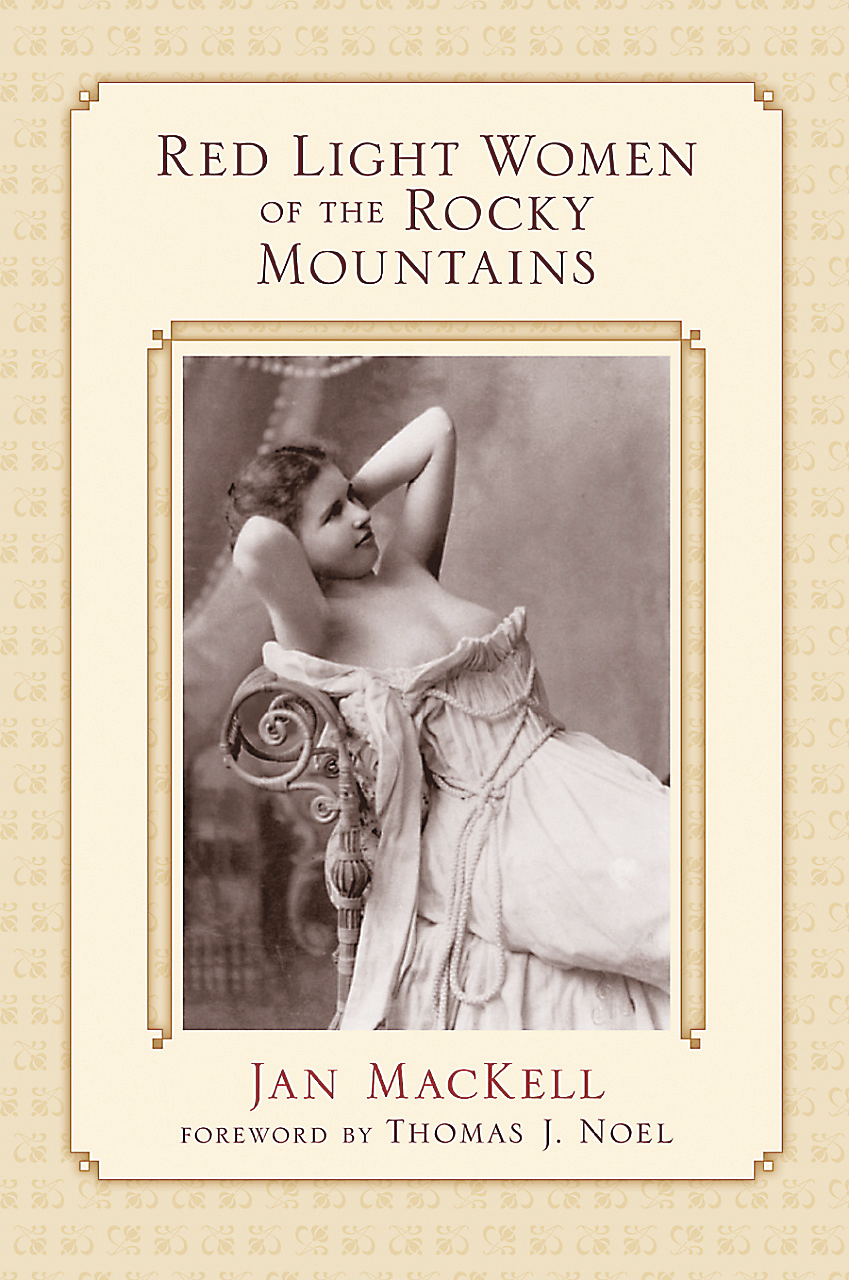

Red Light Women

Holy Hannah! If there ever was a book that tells us just who put the “Wild” in “Wild West,” it’s Jan Mackell’s Red Light Women of the Rocky Mountains (University of New Mexico Press, $34.95). From the sepia-tinted, scantily clad, reclining temptress on the cover, the reader can be sure there’s more to this book than meets the eye.

Shady ladies, soiled doves, women of the night — choose your euphemism for the Wild West’s hardest working girls — they all mean the same thing: The Old West was filled to the brim with women who chose or, as was more often the case, were forced into lives of prostitution. Many women found themselves settling for this, one of the few ways of making a living available to a woman in the male-dominated world of the Old West. In many cases, turning tricks was the only way many mothers, single and married, could feed their children.

The West’s mining camps, cow towns, and burgeoning cities were home to white women from the East seeking egress to a life more exciting than they had known back home. But they were also filled with minorities, who had an even more difficult time carving out a place for themselves in the Old West. Native American, Mexican and Chinese women were so poorly regarded they were often sold as little more than consumable goods, and treated worse than farm animals.

At its peak, Denver’s four-block-long run of brothels, gambling houses and opium dens included the “tenderloin district,” which provided home-offices for nearly 1,000 working girls, many operating out of “cribs” — small dens of squalor with a bed and little else, from which they plied their trade.

Some women such as Laura Evens, Mary “Chicago Joe” Welch, Jennie Rogers, and Mattie Silks (who actually had a sign on her parlor house that read, “Men taken in and done for”) had far more in mind than getting through the day, or night, as it were. Early on in their careers, these notorious and successful businesswomen realized that men would pay handsomely to spend time with a particular sort of woman (wholesome, if only in appearance) in a fancy establishment. So they set themselves up as “madams,” and treated their “girls” with respect. This at a time when most prostitutes received little more than vicious abuse at the hands of unscrupulous male saloon owners (themselves nothing more than thuggish crooks).

But for every take-charge woman who ended up a powerful, if not overtly respected businesswoman, there were thousands who were unable to escape the shackles of this exploitative, demeaning way of life.

In true scholarly fashion, Red Light Women of the Rocky Mountains depicts through obvious diligent research the good and the bad of this fascinating segment of U.S. history. Readers are presented with a clear picture of prostitutes and their trade in the Old West. Mackell teaches us what all those 1950s Western dramas never told us: Not all prostitutes were “soiled doves” with hearts of gold; disease and foul sanitary conditions were rampant; and reaching dotage was an elusive dream.

Mackell’s comprehensive book includes 81 black-and-white photographs, vintage and recent; three appendices listing prostitutes by name in three leading Western towns of the time (Leadville, Colorado, 1880; Butte, Montana, 1902; and Cheyenne, Wyoming, 1880); plus a copious notes section that offers more sources for the subject matter than the average reader would have thought possible.

The book, clocking in at 458 pages, is a hefty accomplishment and gives the impression of being an exhaustive work on the topic. It is Jan Mackell’s passion for her topic (this is her second book detailing prostitution in the Old West) and her conversational ability to carry the reader along in her scholarly yet accessible, engaging narrative — all the while imparting historic information — that helps make Red Light Women of the Rocky Mountains a satisfying read and a top-shelf reference work.

No Comments