24 Nov Books: Writing the West

In 2005, Gary and Jane Ferguson spent five days at a renowned paddling school in Ontario, where they put a little extra polish on their canoe skills amid experts and knocked the socks off of the 25-year-old instructor, who said to them in a note, “I think I’d first like to comment on your communication. It was amazing. I’ve never seen a couple work through the tricky moments as smoothly as you two. You guys have taught me what I’d like my communication to be like in a long term tandem relationship.” Just days later, Jane would die tragically in a canoeing accident on the Kopka River, and Gary would barely make it out with a broken leg. The Carry Home (Counterpoint, $25) is at its heart a very personal story of Jane’s loss and Gary’s struggle to come to terms with that loss and with the seeming betrayal of nature after a lifetime spent in its protection and interpretation. The Fergusons were partners in writing and in life. In their adventuring they are an aspirational guide for couples everywhere.

Taking the personal route is what has made Gary Ferguson’s books on wolves, troubled teenagers, hawks and the stories of the wild so ultimately powerful. You have the sense reading any of his work that he’s thrown himself into the project with a great passion and enthusiasm, fitting himself chameleon-like into any new challenge, absorbing the stories around him and wearing them like a second skin, then translating them through prose and poetry onto the page. His attention to detail in recalling conversations and situations doesn’t seem remotely implausible. And his willingness to turn that attention on himself and examine his personal story as it intertwined with Jane’s story, and then became their 25-year marriage and career together, makes this book singularly effective.

I met Gary in the early spring of 1996 when I was new to the editorial staff at Falcon Publishing. We seldom had authors make their way down the stairs and into our midst, and I had just finished reading Gary’s new book about the first year of the wolves that had just been released into Yellowstone. As a new Montanan, I had followed the story of the wolves closely and for someone new to book publishing, his brand of in-depth journalism, seasoned with the very personal spin that he put into the story set my expectations for future authors pretty high.

By 2005, Gary’s writing career had been inadvertently intertwined with my editorial career for almost a decade as he continued to work on books edited by colleagues. After Jane’s accident, the news moved quickly through the publishing grapevine, leaving those of us who had known of the Fergusons and their work stunned and saddened. Reading his words about her loss now, almost a decade later, you can feel how painfully difficult it was for him to see the world in the same way he did before. He points out as he’s about to leave on his very personal journey to carry Jane’s ashes home:

“I left on a fall morning when the Beartooths were shining, capped by a fresh smear of snow. Driving through our town of Red Lodge seemed normal, which even four months after Jane’s death was confusing: Merv the photographer walking down Broadway on his way to the bakery to sip coffee and swap jokes. Brad, looking serious in his orange patrol belt, waiting to guide the next batch of school kids over the crosswalk. Norm, wearing his one pair of brown Carharts, stooping over in front of the coffee shop, combing the sidewalk for cigarette butts. Suzy out washing the front windows of her store. Mr. Bill strolling up Broadway with his hands in his pockets, trolling for conversation. Long before we ever set foot here, a friend in Idaho told me over a beer that this small town in Montana was a friendly place not overly impressed with itself in the way towns in beautiful places can be. That’s part of why we stayed.”

What makes his story of losing Jane and then finding himself again successful and not cliché is that he brings the same deep journalistic eye to his own story of grief and redemption that he has brought to his other award-winning work. Through his personal and vivid recounting of their life together, this memoir becomes not an epitaph for his wife but a meditation on what it means to be a partner and to choose a life path together. It is also a recounting of the intimate journey Gary took into the wilderness to fulfill Jane’s wish for scattering her ashes in five separate places, a wish that she reminded him of just days before her loss. And it is a celebration of the healing power of wilderness, though not in the sense that the reader will ever think it was easy for him to heal and recover.

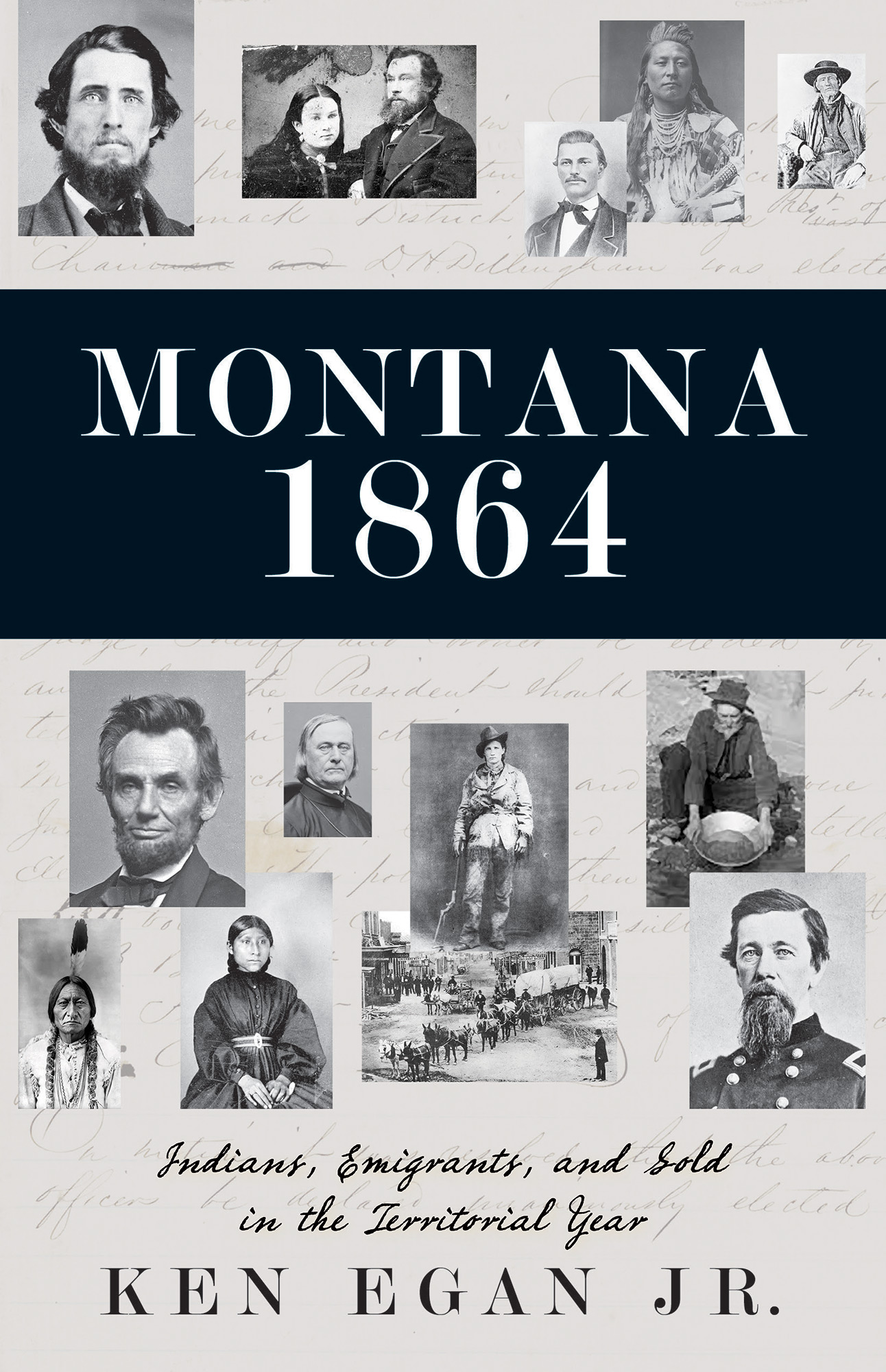

Montana 1864 by Ken Eagan, Jr., (Riverbend $19.95) is as important as it is entertaining, revealing the stories and connections that made up the fabric of Montana’s Territorial Year of 1864. Though readers will be familiar with many of the characters and episodes revealed in the book, the format, the author’s voice and his uncanny knack for making connections between them and the world at large offer a change in pitch that just may do a great service to the historiography of the state for years to come.

Eagan has an instinct for the difference between history and historiography and has a subtle hand to play in the choices he makes in sharing Montana’s story. He uses the Montana Memorial Train of 1964 that traveled from the Treasure State to the Chicago World’s Fair as a sort of touchstone and metaphor for the episodic choices he makes in the recounting of events both grand and ignominious. Even more than that, though, he has a striking appreciation for the packaging and marketing that has been part and parcel of Montana’s story from the beginning, but he doesn’t allow himself to be suckered in by the package.

Perhaps the most striking thing about this book is the fact that as an “anniversary” volume it offers much more than a paean to a glorious and wished-for past, placing Montana’s territorial history in a context that it often lacks. By 1864, the country has been at war for years; the political, philosophical and physical rifts at work in the East have not been unfelt in the West. Eagan deftly reveals the relationships between the epic struggle of the Civil War without adopting a “meanwhile back at the ranch” tone to describe them. He is similarly gifted in his ability to draw connections between Montana’s Native peoples and their voices and their struggles with the invading whites, be they miners or merchants.

The structure of the book is very appealing. For every month of the territorial year he relates what happened for several key characters, adopting a variety of points of view, and in so doing, capturing more truth (as opposed to “fact”) than is typical in a round-up of historical events timed for an anniversary. A book that should be read and discussed, Montana 1864 doesn’t presume to reveal a series of facts and dates or an “official version” of what happened in that fateful year. Instead it paints a picture of what might have happened because of its close connection to the human story and humans’ hands in creating that story, and is all the more valuable for it.

Burt Weissbourd’s thriller, In Velvet (Rare Bird Books, $24.95), is a dark thriller full of science and nature and gritty characters, heroes and villains who could be drawn from real life, and it is just farfetched enough that it won’t keep Yellowstone National Park’s near neighbors up at night with “what if” scenarios, but grounded enough in science and politics to make its thrilling twists and turns allow readers to suspend disbelief as needed. This novel offers enough villains and confusing loyalties to fill several books, as well as a few Western not-quite heroes who try to make things right, all set against the backdrop of modern-day science in the world’s first national park.

The story starts when Rachel, a bear biologist, finds one of the grizzlies she’s been observing feeding on the body of a microbiologist who has been studying thermophiles at a hot spring in the northwest corner of the park. At first, she assumes that the bear, who she has nicknamed Woolly Bugger, has killed Dr. Moody, but she soon realizes that something doesn’t seem quite right. Neither do the hugely palmated antlers starting to appear on the elk living in the area, nor the rising number of newborn animals with severe physical malformations. Of course, nothing is quite right. Men are being murdered, animals are dying and a corrupt local sheriff’s machinations have sent the region into chaos.

Rachel and a former lover, a volatile fishing guide named Rainey, end up working with a Chicago policewoman to fight a battle for the preservation of Yellowstone and the wildlife of the region. While many of the characters and situations that Weissbourd formulates play heavily to type, he effectively keeps the reader guessing about who is really behind the terrible events taking place, and takes his heroes and villains into gray areas that are often missing in this sort of thriller. All in all, it’s an enjoyable and unexpectedly entertaining read.

OF NOTE: Books, Music, Movies & More

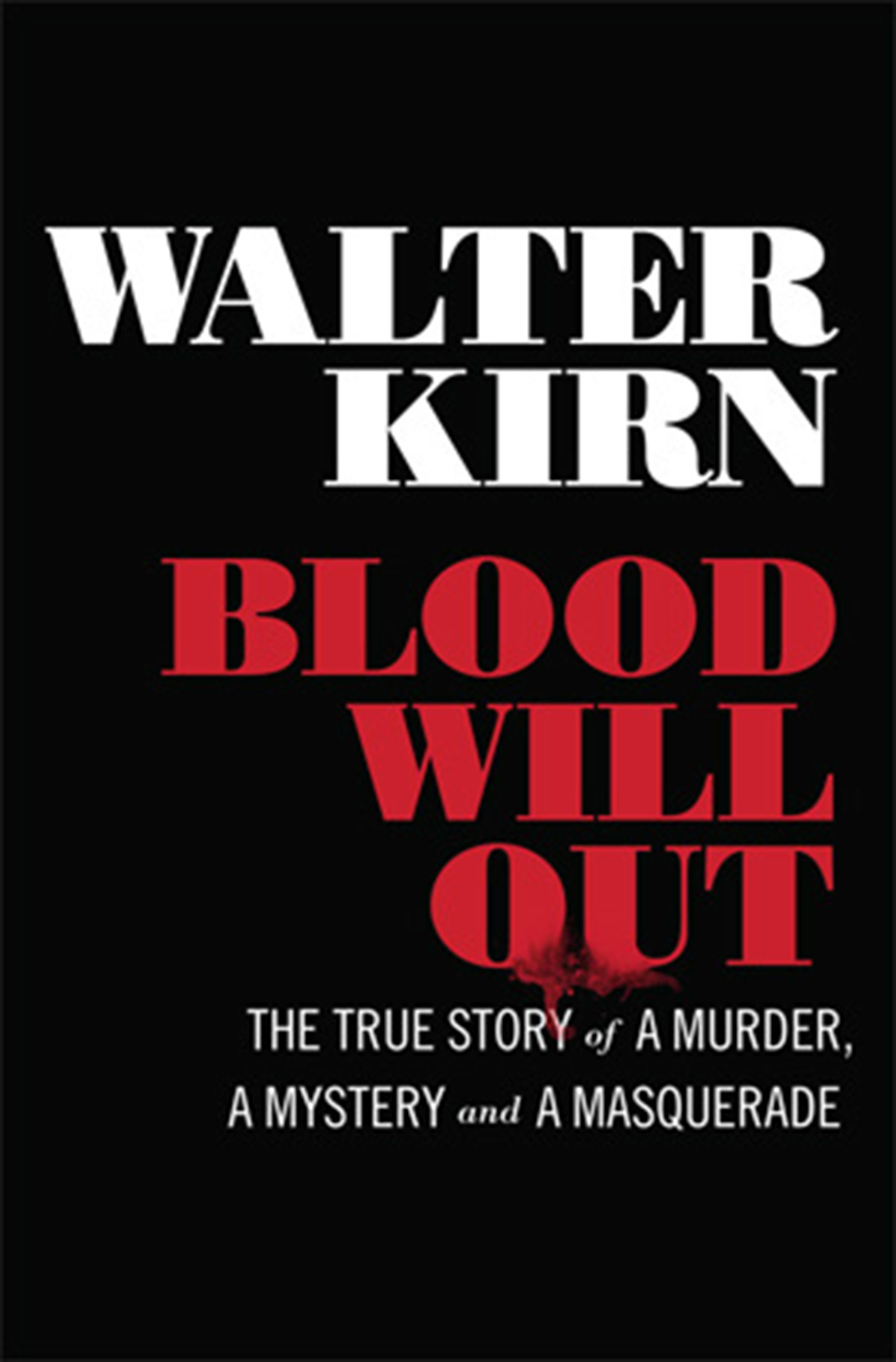

Blood Will Out by Livingston writer Walter Kirn (Liveright, $25.95) offers a view from Montana of the story of Christian Gerhartsreiter, the man who preferred to be known — and passed himself off as — Clark Rockefeller of the Rockefellers for years in the late 20th and early 21st century. The story of this imposter is relatively well known, once his fraud was uncovered and he was tried for the murder of a couple who had once offered him a home; he even inspired a Lifetime movie. What makes Kirn’s story exceptional is his willingness to turn his pen on himself, revealing his credulity as he befriends “Rockefeller” when he travels cross-country to bring him a rescue dog from Montana and continues their odd friendship over the years of continued deceptions. In Kirn’s skilled hands, the story of the imposter and his crimes becomes hard to put down, wondering where the twists and turns of the story will finally end up.

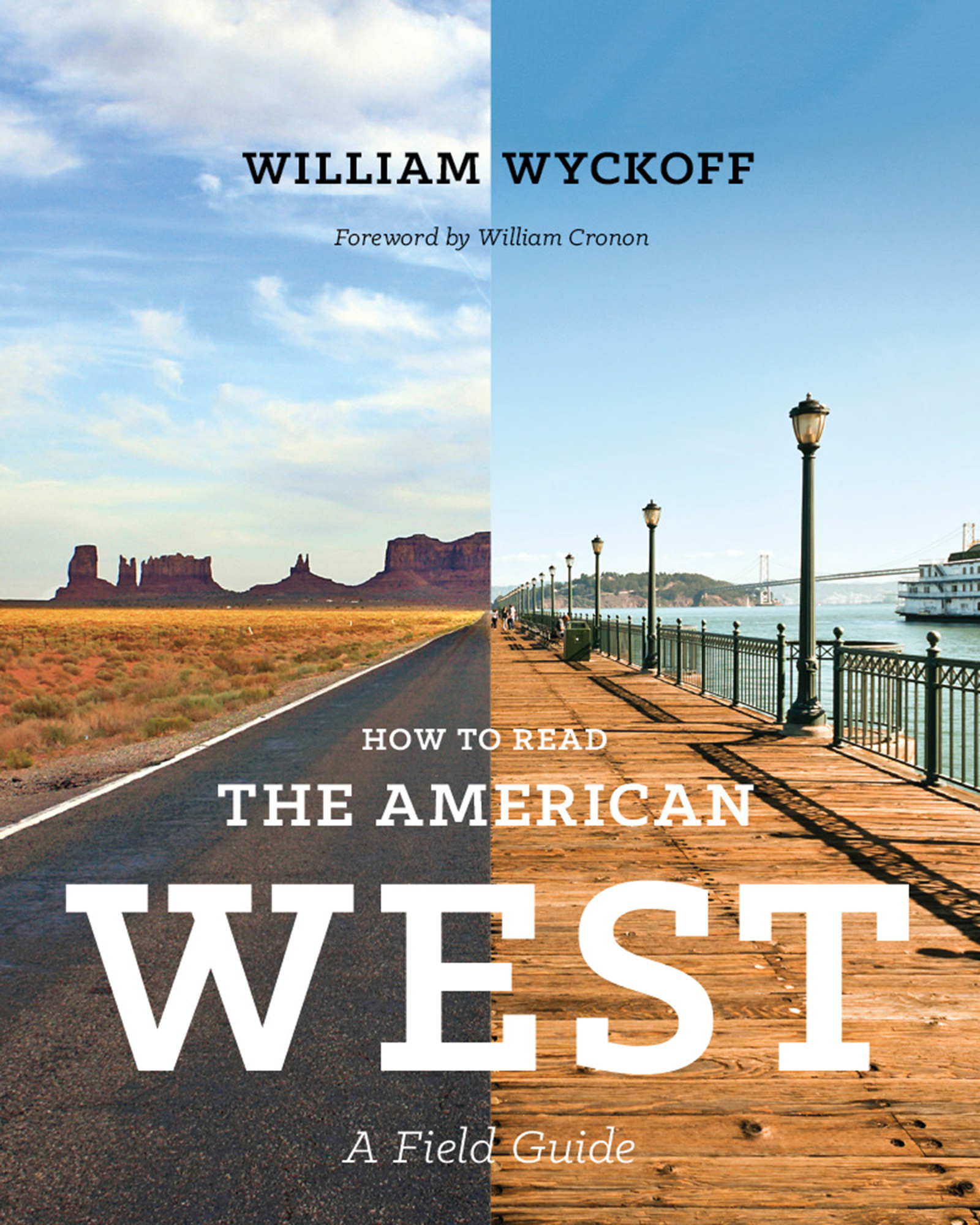

How to Read the American West by William Wyckoff (University of Washington Press, $44.95) bears the subtitle A Field Guide, which is a utilitarian and apt description, but doesn’t capture the enormity of the project or the success with which the author has risen to the challenge of presenting both a guide to and new perspectives on the landscapes of the American West. With beautiful color photography (Wyckoff is an accomplished photographer), maps, diagrams and stories, the book offers an intriguing perspective on the mythical and familiar landscapes of the West while drawing parallels between the seemingly dissimilar scenes travelers and residents see outside their windows. The perspectives that the book offers on natural and human history and how landscape has shaped the culture of the West make this much more than a guide to use for traditional explorations, posing questions about cultural character and the future of the West.

The Montana Medicine Show’s Genuine Montana History by B. Derek Strahn (Riverbend, $15.95) is a rare collection indeed, bringing together more than 100 stories taken from episodes of the author’s popular and very entertaining radio program broadcast on KGLT (originating from Montana State University in Bozeman) the eponymous Montana Medicine Show. These quick glimpses into Montana’s history are made vivid through the use of archival photographs and contemporary accounts of the well-known and little-known episodes and people that Strahn features in his brief accounts that make up the storied past of the Treasure State. A beautifully and easy-to-browse design complements the short-but-sweet nature of these 117 stories, ranging from the life of Butte native Evel Knievel to the noted vaccinologist Maurice Hilleman to the homesteaders of the first part of the 20th century and the fondly recalled Columbia Gardens. It’s a collection that celebrates Montana and perhaps offers a sure-fire cure for either over- or under-romanticizing Montana’s history and people.

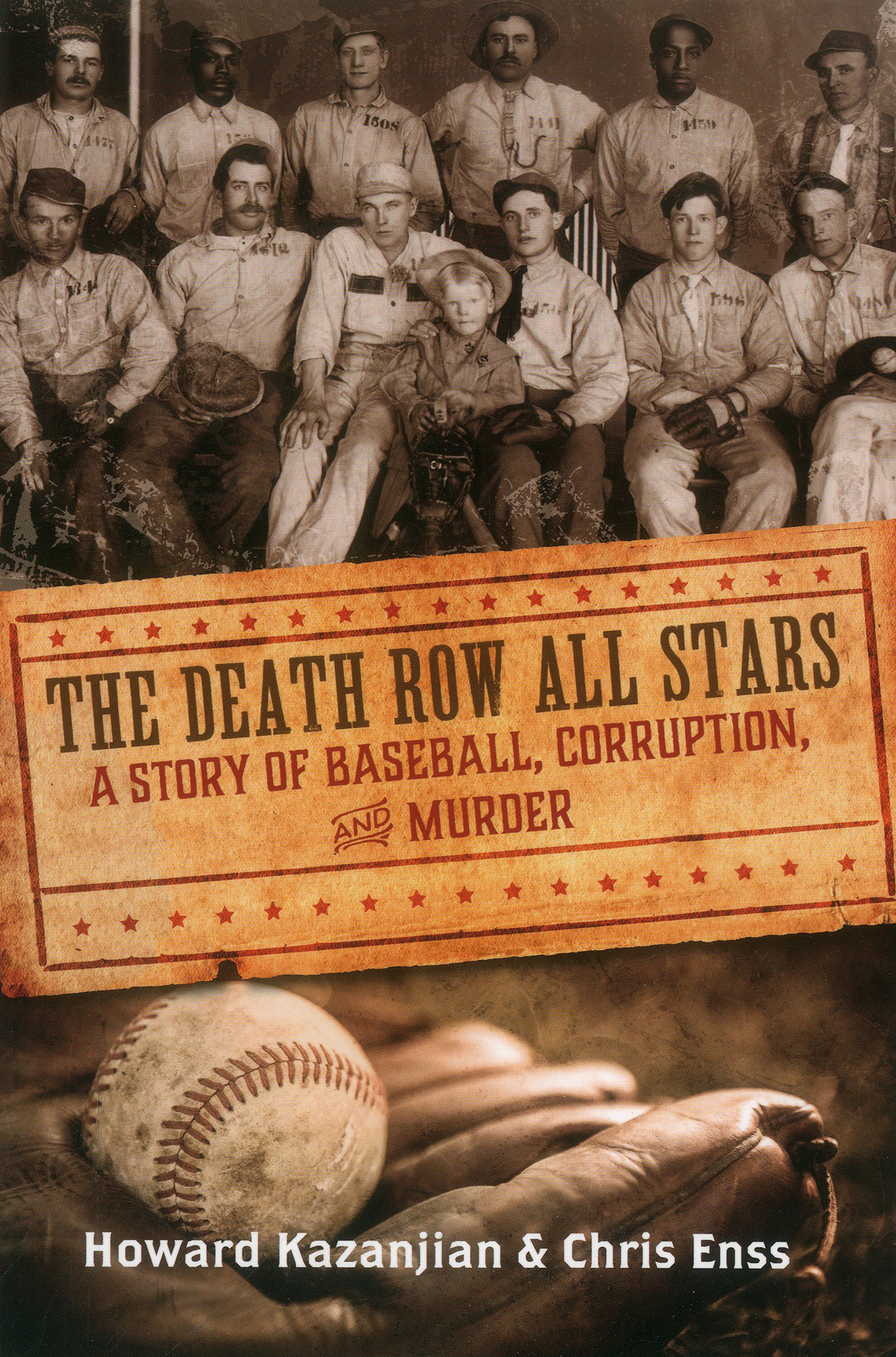

In The Death Row All Stars (Rowman & Littlefield, $16.95) Howard Kazanjian and Chris Enss have turned their cinematic storytelling style to the true story of the 1919 Wyoming State Penitentiary baseball team’s one and only season on the diamond. The team, made up of murderers, rapists and other unsavory criminals awaiting the end of their appeals and the carrying out of their sentences, became a local sensation and seemed to offer promise for the idea of prison reform in the United States. Unfortunately, the workings of greed, politics and gambling behind the scenes belied the pastoral images of the players sitting for their photo in uniform with their mascot — the warden’s young son — at their feet. The truth behind the team’s appearance on the field — each man believing that through his efforts he was “playing for time” — make this a fascinating and revealing story about Wyoming history and immortalizes the efforts of the athletes and the men who made up the All Stars.

Hide and Seek: The Architecture of Cabins and Hide-Outs

For some of us, the longing to build forts in the woods doesn’t end with adolescence. In fact, given the busyness of everyday life, the longing can grow until it manifests as a tiny retreat, a place to seek solitude outside. Hide and Seek (Gestalten, $60) is a contemporary survey of contextual architecture that grew from this longing. Whether located in the forest, on the water or in the mountains; whether light and minimalistic or dark and cozy, the retreats featured in this 256-page book showcase the imagination and ingenuity of shelters that embed their inhabitants in nature.

From a simple, glass-enclosed structure overlooking a lake that’s minimally furnished with a mattress and record player, to a futuristic, mobile dwelling that’s pulled by dog sled and provides shelter for children undergoing therapy, to woven hideaways hoisted between trees and A-frames teetering on rocky Alps’ ledges, these hide-outs help us “reclaim our sense of wonder at the world around us.”

Despite the thoughtful and unique design of each structure, one unifying factor is this: They are mere stopping points amid nature’s splendor.

No Comments