05 Aug Wildly Creative

THERE’S A CANOE HANGING FROM THE CEILING of Dick Idol’s art studio, and it’s not just any old boat.

Purchased from a fur trade museum in Michigan more than 35 years ago, this 16.5-foot Ojibwa birch bark canoe was made between 1850 and 1880 in Northern Manitoba. It’s one of a small number of canoes of its kind to survive the turn of the century, as most were lost to the harsh elements of nature. The origin of this type of vessel dates back several centuries, when they were made primarily by tribes in northcentral and northeastern parts of North America. And because rivers, lakes, and other waterways were the highways that connected the East to the West, over time, the birch bark canoe evolved, serving as transportation for traders and trappers as well as the Native Americans who first created them.

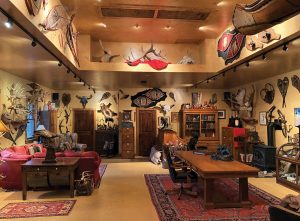

Dick Idol’s collection of memorabilia, displayed throughout his studio, inspires much of his artwork.

This is just one of about 1,200 items on display in Idol’s 2,400-square-foot art studio, housed in a building next to his home on the outskirts of Whitefish, Montana. Sharing wall space with works by some of Idol’s Western art heroes — including David Leffel, Greg Beecham, Raymond Harris-Ching, Dennis Anderson, and Bob Kuhn — is an assortment of antiques and memorabilia that the artist has collected over the past 50 years. Rusted animal traps hang on the walls, along with model bark canoes, functional and ceremonial paddles, antlers, and various keepsakes related to the Hudson Bay Trading Company.

A vast collection of snowshoes, made by Native Americans and pioneers, are reminders of the hardships endured while explorers traipsed through the deep snow. “I used to have 150 or so pairs,” Idol says, “and I was buying the bulk in the ’70s and ’80s. Some are extremely rare and valuable and can’t be found today.”

The interactive monument Wild Band of Razorbacks was commissioned by the University of Arkansas and completed in November 2018.

Display cases hold smaller keepsakes, such as handcrafted Native American folk art pieces. Antique furniture is sprinkled throughout, including a wooden file cabinet and display cabinets that are reminiscent of those found in the general stores of the Wild West. Bookshelves are filled with reference volumes on subjects ranging from Native American and fur trade era history to wildlife guides and books about the world’s greatest artists and Western works.

All of this represents Idol’s deep-rooted passion for wild places, the hardy people who braved them to explore the Western Frontier, and the Native Americans who perfected the art of living off the land. “I’ve always been interested in the fur trade era,” Idol says. “I have so much respect for the kinds of people they were, before roads, refrigerators, and houses. They suffered incredible hardships but invented ingenious things to help them survive in the wilderness.”

Last Light | Oil | 24 x 30 inches

Idol’s studio consists of three separate spaces, all of which exhibit parts of his collection. The large center area is where he creates his main body of work, both paintings and sculptures. The room on the south end of the studio serves as his design space, a storage area for reference material, and a place for drawing, framing, and varnishing. A separate room on the north end serves as the main office where Idol’s wife, Toni Rae, takes care of the company’s business affairs. Across the road, Idol uses a large metal building with high ceilings to work on monument sculptures, molding, and furniture design.

His collection, which overflows into the couple’s house, also represents a life that’s been filled with unimaginable outdoor experiences, and a successful and wildly diverse career that, in a circuitous way, eventually led Idol to the world of art.

Golden Eagle with Rattlesnake | Bronze | 30 x 26 x 16 inches

Idol grew up in rural North Carolina. He attended North Carolina State University on a full-ride football scholarship and was wooed by the NFL upon graduation. But an overriding drive to pursue the outdoors led him to Alaska instead, where he learned the taxidermy trade and started guiding, outfitting, and booking hunts for big game clients around the world.

In the 1970s, Idol started collecting whitetail deer antlers, and says he “ended up with the best collection in the world. … My dad used to say, ‘Dickie, when are you going to quit playing with those deer antlers and get a real job?’” Idol recalls. His collection now resides in the Bass Pro Shop’s Wonders of Wildlife Museum in Springfield, Missouri.

That “real job” came to fruition when Idol co-founded North American Whitetail magazine in the ‘80s, and took his antler collection on tour. Considered an expert on the topic, he spoke at seminars, helped launch whitetail shows in several states, wrote books and articles, and created instructional videos, television shows, and product endorsements, becoming a widely known name in the hunting world.

Idol’s studio could pass as a museum, displaying everything from antique animal traps and snowshoes to Hudson Bay Trading Company keepsakes and Native American folk art.

Backed by that recognition, Idol launched the “Dick Idol” brand, in which he infused his love of the outdoors into stylish designs for furniture, lighting, floor coverings, accessories, and other home decor products. Idol created hundreds of sculptures in bas-relief that were applied to many categories of furniture and accessories. “It resonated with a lot of people,” Idol recalls, “and soon became one of the most recognized lifestyle brands in the home furnishing industry.”

In the late 1980s and early ’90s, Idol realized a genuine passion for creating art. He fully embraced painting, drawing, and sculpting tabletop bronzes, and he began taking on commissions for large monuments. Among many others, his latest and possibly his most dramatic work took four years to complete: The Wild Band of Razorbacks monument sits on the perimeter of the Razorback stadium, home of the Arkansas Razorbacks football team. With a footprint that’s 50 feet wide and 25 feet tall, this interactive sculpture includes water features and specialty lighting.

An original 16.5-foot birch bark canoe, made by the Ojibwa tribe in Northern Manitoba between 1850 and 1880, is believed to be one of only a few original Indian-made birch bark canoes to survive the turn of the century.

These days, Idol’s life revolves more around painting. Due to the amount of time it takes and the complexities involved in creating monuments, the artist claims that, for him, large works like the one in Arkansas might be a thing of the past. “Part of it is my age,” he says. “I’ve only got so many more big ones left in me. I’ll probably get other offers, but I’d have to think long and hard about it.” And in 2017, he and Toni Rae passed the ownership of their downtown Whitefish Dick Idol Signature Gallery to Idol’s son, artist Colt Idol, and his wife Jennifer.

On any given day, Idol walks over to his studio around 9 a.m., and he typically paints until the afternoon. “I like to mix my oil paints in the morning so they’re usable all day,” he says. “You get to a point where you’ve been looking at a painting all day and lose your objectivity; you’re just pushing paint around. So around 4 p.m., I usually do something else to end the day.”

The racks of two bull moose from Maine were found locked together, and even today will not separate. The moose in back was a world record until recently, and is currently the second largest.

Idol notes that his painting style is still evolving. Drawing inspiration from the collection that surrounds him and from a lifetime of outdoor experiences, he’s working more on technique without locking himself into a particular subject matter. He especially loves to use light, and plans to incorporate different approaches into many of his future paintings.

One unique item in Idol’s collection is a tree that grew around an antique trap and chain. “In all likelihood, this trap and chain was draped over a limb when the tree was small,” Idol says. “I’ve owned this collectible for over 40 years, and by counting the growth rings in the log, this piece is more than 130 years old.”

“Backlighting is a technique I would like to use more,” Idol says. “I’m finishing a wolf painting right now called Snow Ghost. The wolf is backlit and has rim lighting that makes it more striking. Painting is really what I want to be doing now, at least for most of the rest of my life.”

No Comments