20 Aug Fish Tales: Whoa, Nice Tetons

MAYBE IT’S BECAUSE AFTER SIX DECADES of fishing mostly the same places I’ve convinced myself I can fish, in the same way that singing Siegfried in the shower makes me think I’m a great heldentenor operatically buttering up Brünnhilde and not what I really am: Elmer Fudd twying to kill da wabbit.

Maybe it’s the intimidation factor. All those huge brawling rivers filled with huge brawling trout that spurn effete Eastern flies and shatter wussy Eastern rods and knock off our bowler hats and pince-nez and administer a good-ol’-boy butt-whuppin’.

Maybe. But I’m not quite that kind of Easterner. I grew up an honest-to-Jed-Clampett hillbilly in the East Tennessee mountains and have lived nearly 40 years in a bare-knuckle corner of blue-collar Maine, which has its own brawling rivers filled with wild brook trout measured in pounds and hyperkinetic landlocked salmon that peel fly reels to the bare spool before you realize you’ve hooked one.

So what I’m thinking is, it must be the scenery.

It’s not that we don’t have scenery in the East. It’s just that our scenery is ancient and eroded and softly subdued — carpeted with trees, for the most part hidden behind trees. And it’s not that I’ve grown blasé about Eastern scenery. It’s just that I can’t really see much of it from trout-stream level.

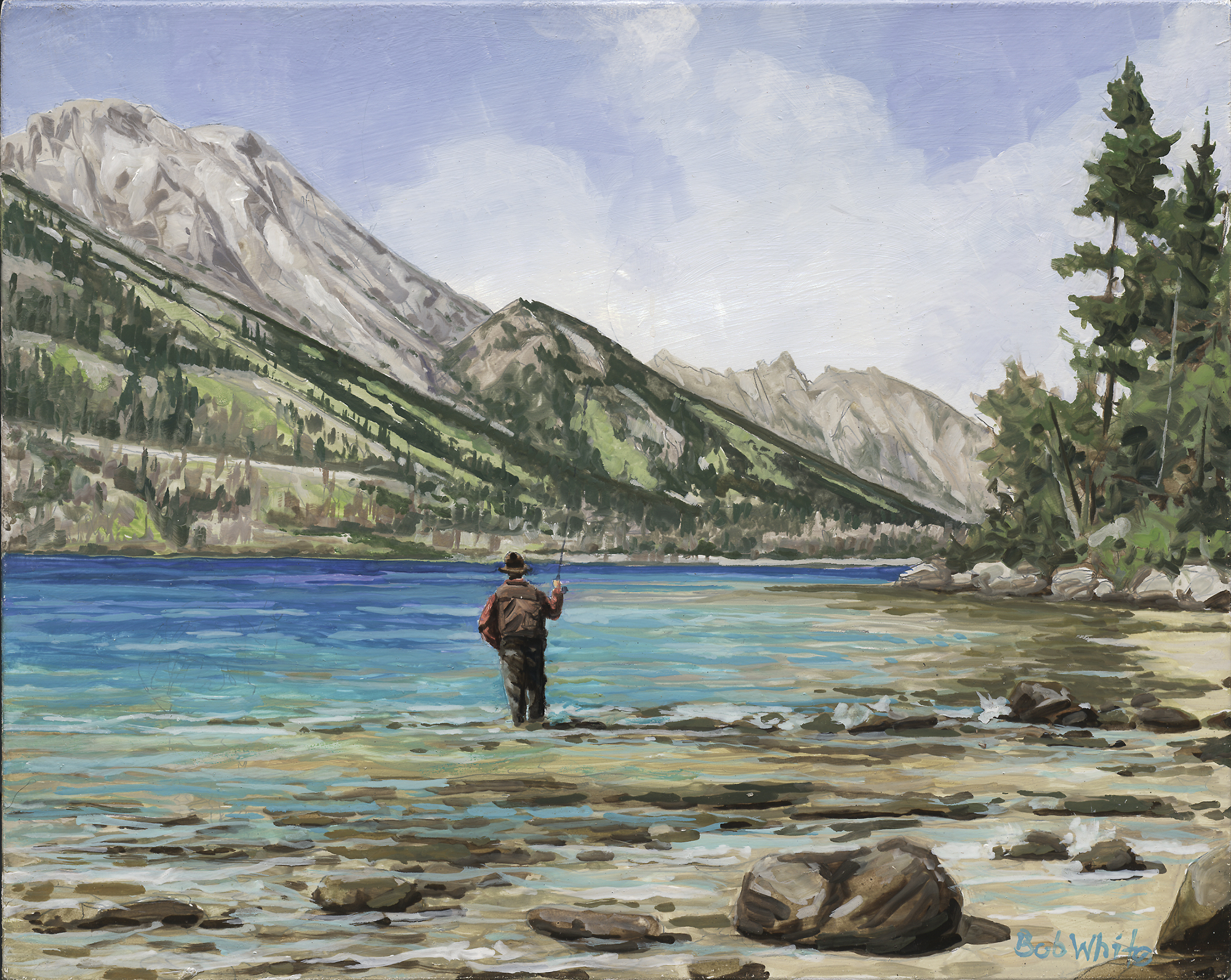

But the Rocky Mountain West is different, the scenery is flagrant and in-your-face and impossible to hide, impossible to ignore even fishing the tiniest trout trickle. Wherever you look, there it is — behind you, in front of you, all around you: The Front Range. San Juans. Wind Rivers. Beartooths. Beaverheads. Big Horns. The Absarokas. The Crazies. The Madisons. Name a Western mountain range, and I’ve lost a good trout gawking at it. The biggest brown trout I ever saw outside a hatchery stud farm tried three times to eat my South Fork Stone in a tight corner of the Madison, and I just stood there with my mouth open watching the sunset spatter its entire palette of reds and purples across the craggy canvas of Sphinx Mountain.

But the worst offenders — or, seen another way, the best offenders — are the Grand Tetons. As a permanent member of the seventh grade, I feel a filial bond with the 19th-century French voyageurs who Alouetted and Frère Jacquesed their way into Jackson Hole, looked up from the fruited plains at those purple mountains’ majesty and said: “Nice rack.” Or, more accurately: “Sacre bleu! There’s three of ’em.”

On my first trip to Jackson Hole, I couldn’t tear my eyes away from the polymastian magnificence of Teewinot, Owen and Grand Teton, thrusting a mile and more from the valley floor, Brünnhilde’s granitic bustiere dominatrixing the skyline. I nearly did a face-plant doddering down the jetway, nearly fell out of the driftboat trying to keep them in sight, missed cast after cast and strike after strike, as mesmerized as a seventh-grader tossed into the girls’ locker room, a goober-brained Gomer Pyle endlessly going, “Golleeeee.”

I finally hooked a really good fish we saw rising in a secluded slough, a small tree-covered bluff blocking the view, another blocking the restless wind that incessantly blew. It was 20 feet farther than I usually can cast, with a 20-foot upstream reach I usually can’t do, hitting a small distant target I usually can’t hit. But everything worked out more or less by accident, and the big black snout pierced the film and snarfed the Adams Parachute and headed for the open river.

After his first run I muscled him close enough to see 2 feet of cheddar-yellow cutthroat, but on his second run he towed me around the corner and into the river and there, towering over the landscape, rim-fired by the late-afternoon sun, stood Brünnhilde’s triple-brass breastplate: the Grand Tetons. Worse, across the slough a moose cow and her twin calves stepped delicately into the river and began to drink, as precisely composed with the mountains as a Chet Reneson painting.

I think I lost the trout. I can’t quite remember. But I’ll never forget the scenery.

No Comments