09 Aug Tucker Smith’s Celebration of Nature

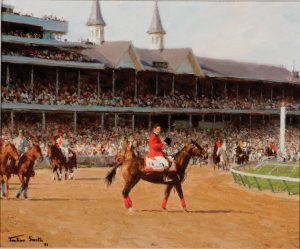

In 1991, just as his career was about to take flight Tucker Smith created a 10-by-12-inch painting of a scene he’d observed at the Kentucky Derby. Capturing the commotion before the post parade, “Derby Day” depicts horses and riders entering the field in front of a grandstand packed with onlookers.

As he stood in front of this painting almost 30 years later, Smith — now 80 years old — was flooded with memories. This one, along with 92 of his other original works, was on exhibit at the National Museum of Wildlife Art in Jackson Hole, Wyoming, for the touring retrospective Tucker Smith: A Celebration of Nature. Serving as a timeline and a visual representation of his evolution as a professional artist, the pieces on display ranged from his early years to the present day. But “Derby Day,” in particular, caught his attention.

RETURN OF SUMMER

OIL ON CANVAS | 30 X 42 INCHES | 1990

Prix de West Collection, National Cowboy & Western Heritage

Museum 1990.29. ©Tucker Smith ©1991 Courtesy of

The Greenwich Workshop Inc., www.greenwichworkshop.com

“When I saw it there years later, I liked the idea of it, but at the time, I don’t think I had the courage to do a large painting of it,” Smith recalls. He borrowed it back from the collector, and — now with a lot more confidence and skill under his belt — re-created it on a 30-by-36-inch canvas. “At this point, I took it on as a challenge because I knew it would be,” he says.

The artist is never one to back down from a challenge. When he’s not exploring the Wyoming backcountry around his winter home near Jackson Hole and summer home at the base of the Wind River Mountains in Pinedale, Smith paints seven days a week. “I’m still trying to learn; that’s the way I think,” he says. “How can I be better, and how can I solve the problem of the painting I’m working on? At 80, it’s gratifying to be able to still take on a challenge.”

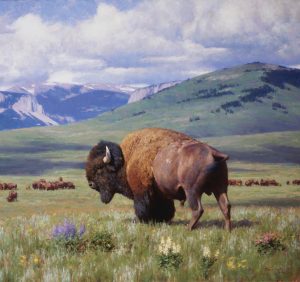

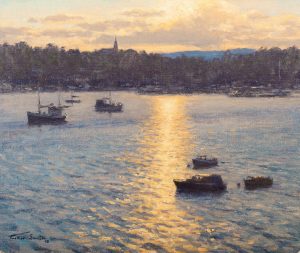

Smith has been largely regarded as a contemporary wildlife artist, focusing on the Rocky Mountain landscapes and creatures that have been a central part of his life. But the retrospective — on display at the National Sporting Library and Museum in Middleburg, Virginia, through August 22 — tells a different story, making it clear that the artist has challenged himself throughout his career by depicting a variety of subjects, ranging from working horses, cowboy camps, and lively ranch scenes, to architecture, seaside settings, and other diverse landscapes.

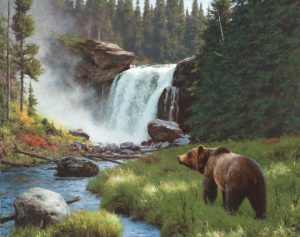

MOOSE FALLS, YELLOWSTONE NATIONAL PARK

OIL ON CANVAS | 32 X 40 INCHES | 2014

Purchased from the estate of Tony Greene with funds generously provided by Susan and John Jackson; Joffa, Kavar,and Bill Kerr; Frank Sands; Maggie and Dick Scarlett; Rosella Thorne; and Georgene Tozzi. Collection of the National Museum of Wildlife Art ©Tucker Smith

“People generally think of me as a wildlife artist,” Smith says, “but I don’t think of myself that way. … I’m a nature painter.”

When Smith was 12, his family moved from Minnesota to Pinedale in search of a drier climate for his mother and brother, who both suffered from asthma. The landscape was “a lot more wild and wooly” than anything he’d ever experienced, and Smith quickly fell in love with the natural world. He worked for the U.S. Forest Service in the Wind Rivers after high school, and that “got me into the mountains,” he says, “and I got to know them. It was a good way to grow up.”

Smith was attracted to art at an early age, and he took naturally to drawing. But with no art classes at his small rural school, he was self-taught until he attended the University of Wyoming, where he majored in mathematics and minored in art. After graduating, he and his high school sweetheart-turned-wife, Jean, moved to Helena, Montana, where he worked as a computer programmer and systems analyst for the state for eight years while painting on the side. In 1971, with Jean’s support, Smith replaced the keyboard with an easel and tried to make it as a full-time artist.

It wasn’t long before a painting of draft horses drew the attention of The Greenwich Workshop, and the fine art publishing house requested a limited edition print. “That got my career going around 1976,” Smith says, “and it grew from there.”

The artist credits the Montana Gallery in Helena and the Carson Gallery in Denver, Colorado, for helping him draw collectors early on. But Smith’s big break came in 1990, when he won the National Cowboy and Western Heritage Museum’s prestigious Prix de West Purchase Award for his painting “Return of Summer.”

Byron Price — the museum’s executive director at the time and currently the director of the Charles M. Russell Center for the Study of Art of the American West at the University of Oklahoma — has followed Smith’s career ever since, and he served as a guest curator for the retrospective.

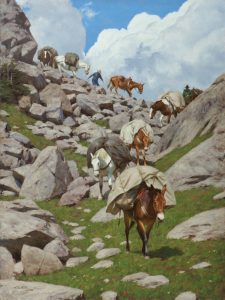

“His paintings are always carefully composed with balance and harmony, and invariably have a distinct point of view and a clear and satisfying path for the viewer’s eye to travel,” Price writes in the exhibit catalog. And he would know, not only because of his comprehensive background in Western art, but also because he looked at one of Smith’s paintings, “Box R Pack String,” just about every day for 15 years. Borrowed from the collection of Joffa and William Kerr, founders of the National Museum of Wildlife Art in Jackson Hole, it hung in Price’s office, and he “reluctantly gave it up” for the retrospective. “I never got tired of it,” Price says. “The way he handled the subject, the tight composition. He has great depth perception and is able to evoke that in the receding plains. He does work that provides a path to lead you through. … You never lose your way in a Tucker Smith painting.”

DERBY DAY

1991 | OIL ON CANVAS | 10 X 12 INCHES

Collection of Curtice and Bob McCloy ©Tucker Smith

In 1994, William Kerr commissioned Smith to paint Jackson Hole’s National Elk Refuge, resulting in “The Refuge,” a 36-by-120-inch piece that has been a signature in the National Museum of Wildlife Art’s collection ever since. This marked the beginning of a long relationship, and the venue has since hosted numerous exhibitions featuring the artist’s work.

Smith has also participated in most of the country’s major Western art events, picking up a number of awards along the way, including the Pix de West’s 1996 Robert M. Lougheed Memorial Award; the 1999 Thomas Moran Memorial Award for Painting at the Autry Museum’s Masters of the American West; the 2007 Autry National Center’s Trustees’ Purchase Award; and the 2008 Governor’s Art Award through the Wyoming Art Council, among many others.

It’s not lost on Smith that he’s often standing on ground once occupied by Western art masters, including Thomas Moran, Albert Bierstadt, Carl Rungius, and Charlie Russell. Connected to these painters by their shared love for wild places and life in the West, he has studied their work extensively. “Tucker is a student of history,” Price says. “One of the things that helped strengthen his painting is his knowledge of these artists’ work. He follows in their footsteps, but he’s seeing different scenes at different times and in different light.”

THE BRANDING | OIL ON CANVAS | 16 X 28 INCHES | 1988

Collection of Curtice and Bob McCloy ©Tucker Smith

Each year, Smith takes a week-long horse-pack trip into Wyoming’s Wind River Range, a tradition he started with artist Clyde Aspevig in 1988. He is also often accompanied by other respected Western artists, including Ralph Oberg, Andrew Peters, Bill Anton, Kathryn Mapes Turner, and more. “It’s like a wildlife and landscape who’s-who,” Smith says. “And it’s a give-and-take, we’ve all learned from each other.”

On trips like these, Smith takes time to observe not only the landscapes and the wildlife that reside there, but also the subtle nuances highlighted at different times of day and in different seasons: the changing colors, light, textures, and other details that the average person might not notice. Smith photographs the elements that intrigue him, oftentimes including more than one into a painting.

Working diligently on one piece at a time, he uses his photographs to create authentic scenes that collectors are drawn to, but — unless they’re willing to make the arduous trek into the backcountry — will likely never see in person. Just as Moran documented Yellowstone in the 1870s, before travel there was common, Smith has served as an interpreter of some of the West’s most stunning landscapes and the creatures who inhabit them. “You paint what you know,” Smith says. “Nature has always been what I was interested in, and it’s what I know.”

MONTE’S SHORTCUT

OIL ON CANVAS | 48 X 36 INCHES | 2005

Collection of the artist ©Tucker Smith

The retrospective — an idea initially spurred by William Kerr and his daughter Kavar — took three years to pull together. Curator Tammi Hanawalt helped plan the exhibit, while Smith tracked down paintings from collectors, some of which he hadn’t seen for more than 30 years. The exhibition opened at the National Museum of Wildlife Art on June 15, 2020.

“Seeing all my work together was a great pleasure, and an eye-opener for me,” Smith says. “To have it all there, the great variety, I could see my growth. I could look at those paintings more objectively than I look at my present work and appreciate them for what they are.”

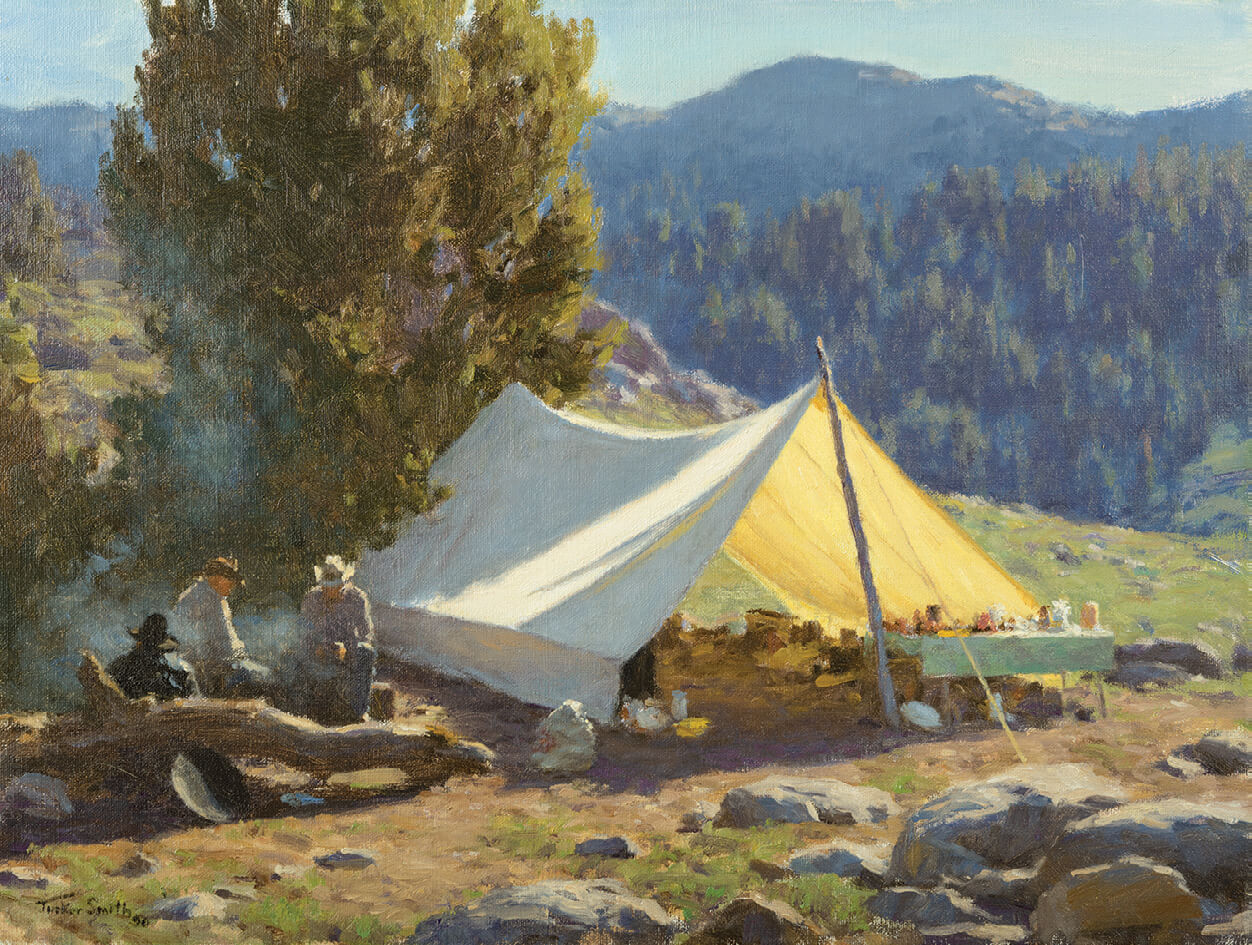

MORNING CAMPFIRE

OIL ON CANVAS | 20 X 24 INCHES | 2009

Collection of the artist ©Tucker Smith

Smith was also able to see how his style had evolved and loosened up over time. “When I was starting out, it was fairly tight work with a lot of detail,” he says. “Then I got more confident; and with more confidence, you can develop a looser, easier way to describe something.”

But Price explains that, in his opinion, the quality of Smith’s work has remained constant. “To me, he was born full-grown as a painter,” he says. “I think he’s only gotten better at his compositions, and his strength is in finding those details that make an ordinary scene extra special. He reminds us that there are still open spaces and wildlife, and through his art, we get to revel in it like he does.”

The traveling exhibit allows viewers around the country to also revel in Smith’s interpretations. And like the Western masters who stood in many of the same wild places and painted some of the same landscapes a century before him, he’s offering a fresh perspective.

OSLO SUNSET

OIL ON CANVAS | 10 X 12 INCHES | 2002

Collection of Joffa and Bill Kerr ©Tucker Smith

“Tradition need not be replaced by something new,” Smith writes in the exhibit catalog. “It can be respected, understood, and serve as a foundation to be built upon. I don’t pretend to be able to represent the levels that fine art has achieved and can attain, but I do think I represent tradition. Tradition is what makes us who we are and allows me to celebrate nature.”

A Celebration of Nature will be on display at the National Sporting Library and Museum through August 22, 2021, and then at the Booth Western Art Museum in Cartersville, Georgia, from September 11 through January 2, 2022.

No Comments