29 May TrailBlazing

Marty Bannon is perpetually in a hurry. He’s eager to get his words out, his work accomplished, and his point across. His nickname “Race” describes his personality as well as his background as a pilot, runner, and long-distance hiker. Now “retired,” Bannon has a new challenge: creating and promoting the first statewide trail that connects the cloud forests of northwest Montana with the island mountain ranges of central Montana and the rolling prairie and big rivers of the eastern half of the state.

It’s called the Montana Trail 406, and if Bannon is someday successful in his pitch to legislators, it will be designated as Montana’s official state trail, the same way the Continental Divide Trail has a special designation as a national scenic trail or the Lewis & Clark Trail as a national historic trail.

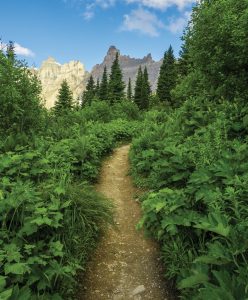

PHOTO BY SETH ROYAL KROFT

The 1,800-mile Montana Trail isn’t a new thoroughfare. Instead, it connects dozens of existing routes, including 42 designated trails across national forests and wilderness areas, remote county roads, Bureau of Land Management two-tracks, and flowing rivers to stitch a path across the state that is more than the sum of its parts.

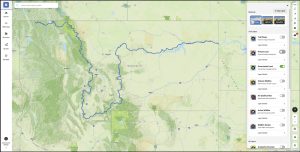

Even without a legislative resolution that adds the state’s seal to the route, the Montana Trail 406 already exists, both on the ground and as a line on maps. That includes onX’s Backcountry app, which has charted the Montana Trail 406 on its popular digital platform. It’s the manifestation of a dream to take east and west the network of trails that has, for a century or more, mostly run north and south across Montana’s mountains.

Montana Trail volunteers erect directional signage on a ridgeline section of the cross-state trail. The route follows designated trails for much of its 1,800 miles, but junctions require clear signage. | PHOTO BY RACE BANNON

“In 2015, I hiked the length of the [3,000-mile-long] Continental Divide Trail and was hooked by long trails,” says Bannon, who lives in Great Falls. “From fellow hikers, I started learning more about these state trails. There’s the Arizona Trail, the Colorado Trail, the Florida Trail, and probably others I don’t know about. I’m pretty secular in my opinion that Montana has more handsome and interesting landscapes than those other states, and I realized that if we connected hundreds of miles of existing trails, we could create a state trail to connect public land, small towns, and places that most Montanans have never seen.”

The Montana Trail follows the shoreline of jade-green Grinnell Lake, deep in Glacier National Park. | Photo by SETH ROYAL KROFT

The Montana Trail has a website (montanatrail.org), a board of directors, and a growing number of evangelists, advocates, and users. That includes Carly Swisher and Felicia “Fey” Reynolds, both of Missoula, who are among the first hikers to complete the entire trail. They spent 58 days on the trail in 2022, often finding their own way when the digital breadcrumbs vanished.

“There is something to be said for the well-established trails that tell you exactly where to go every step, but there’s something just so wild and beautiful that comes with a route like this,” says Swisher. “I guess what makes this trail so unique is that you get a variety of experiences.”

A Spectacular and Meandering Route

The trail starts on the Idaho border and follows the Pacific Northwest Trail across the Kootenai and Flathead national forests, just south of the British Columbia border, to the tiny North Fork Flathead River village of Polebridge. The route then enters Glacier National Park, where it intersects the Continental Divide Trail to Marias Pass on U.S. Highway 2. The Montana Trail then wends through the Bob Marshall Wilderness Complex to MacDonald Pass above Helena, then Homestake Pass above Butte before traversing the Pioneer, Tendoy, Snowcrest, and Gravelly mountains of southwest Montana. The next stages pass through the Madison and Gallatin ranges before taking a restorative dip at Chico Hot Springs, the trail’s midpoint.

The trail’s western terminus is on the Idaho state line. Going east, it crosses the Kootenai and Flathead national forests before wending through Glacier National Park, then following the Continental Divide Trail. The digital app onX Backcountry designates the trail while providing users with information about land ownership, amenities, and trail alerts.

From Chico, the trail runs through the Absaroka Beartooth Wilderness, emerging at Livingston before traversing the Crazy Mountains, then the Castle, Little Belt, and Highwood mountains. After following county roads to Fort Benton, the trail becomes a waterway down the Wild & Scenic portion of the Missouri River to Kipps Landing, on Highway 191 between Grass Range and Malta. The trail then follows the remote Missouri River Breaks all the way to Fort Peck, where trailgoers can choose to float the lower Missouri River to the North Dakota border or hike and bike gravel county roads to Culbertson and, thence, the North Dakota line.

Whew.

That’s a lot of ground, but Bannon and other trail advocates don’t expect users to tackle it in one big season. Instead, they imagine it will become a cumulative challenge as users tick off a couple of segments a year.

But the trail’s route can also accommodate those ambitious thru-hikers who want to spend an epic season on the Montana Trail. It can also transport two-wheeled travelers. In places, an alternative route accommodates bikers who aren’t allowed in wilderness areas or where a loaded bike might not be able to traverse steep or exposed trails.

“It’s unique for thru-hikers because it needs to be hiked from west to east in order to complete the river sections without paddling upstream,” says Great Falls writer Amy Grisak, one of the early contributors to the trail’s creation. “This means starting late enough in the season to be able to make it through the snow in the high elevations, yet not being snowed or rained out by early weather in September or October in the Missouri Breaks.”

The path follows the Continental Divide Trail through the Bob Marshall Wilderness Complex, then south through the Pioneer, Tendoy, Snowcrest, and Gravelly mountain ranges before crossing the Madison and Gallatin ranges. Its central and eastern segments follow rivers and prairie roads. | PHOTO BY RACE BANNON

Although the trail has 25 distinct segments, Bannon thinks of it as two halves, the mostly mountainous western half and the mostly riverine and prairie eastern half, naturally connected at Fort Benton.

“Compared with the Arizona Trail, where hikers have a 10-month hiking season, the Montana Trail is constrained by the weather,” says Bannon. “Because we’ve included so many mountain ranges, the Montana Trail is a high-elevation route, and it’s a short window when you can hike a lot of it without doing some mountaineering or winter hiking. To me, the best way is to start at Fort Benton and go east when there’s abundant water to float and the prairie is green with flowers and grass. Then, come back and hike Fort Benton to the Idaho border as the snow melts after the Fourth of July.”

The trail is open to uses allowed by land managers. Some segments outside wilderness areas are designed for mountain bikers. | PHOTO BY RACE BANNON

That cleavage acknowledges Fort Benton as the either-way trailhead that it’s been since steamboats brought gold miners to Montana in the 1860s and sent boats back downstream loaded with Montana’s riches. It salutes Fort Benton “as Montana’s original trail town,” says Bannon.

The Challenges of Route Finding

If Bannon had the idea and the inspiration, he needed professionals to translate his Montana Trail from a jumble of field notes and Sharpie-scrawled lines to a route that anyone could find and follow. For that, he enlisted the help of two professional mapmakers: the U.S. Forest Service’s Rob Ahl and Phil Davis, who now works for Missoula-based onX.

Ahl and Davis are friends and colleagues who share their delight for mapping and backcountry recreation. Together, they converted Bannon’s vague route into lines on maps and eventually a contiguous digital trail for onX.

“One of the most intriguing parts of this project is the fact that Marty [Bannon] wasn’t necessarily creating any new trails; he was just stringing together routes that exist, whether backcountry trails or public roads,” says Davis.

But Ahl says those areas where one established route ends and the next one starts aren’t always clear, and the mapmakers were often reliant on Bannon’s anecdotal field notes to link the two.

“As GIS [global information system] specialists, we are used to dealing with big digital files of spatial data,” says Ahl. “But often, we had to decipher Marty’s handwritten notes or hand-drawn maps when it came to linkage points. He might write, ‘Take county road XYZ a few miles to the junction, then take the right fork and continue to the stop sign. Go straight to the trailhead.’ We’d have to translate that to a line on a map that anyone could follow.”

But Ahl says route finders have faced a bigger challenge, as they want to keep the trail on publicly accessible land. Sometimes, that requires leaving traditional trails and following roadways to the next trailhead or river put-in.

“It’s not hard to map an existing route,” he says. “The difficulty comes in where you don’t have existing trails and have to improvise and think about the route from a user’s perspective. Does the trail become needlessly long because you have to go down this county road forever, or does it cease to be interesting when you have to walk on a highway for 20 miles?”

A Living Route

Here’s where the linear, analytic world of cartography bumps up against the arbitrary, changeable physical world. Bannon’s team acknowledges that the route of the Montana Trail, especially where it enters the relatively unmapped Missouri River Breaks, is based on best guesses and directions that make the most sense for most users in most seasons. But that may not ultimately be the best trail.

“This is the biggest challenge and the most exciting opportunity that I see,” says Ahl. “The trail is living. What you see on a map is a starting point, but we can continue to refine and enhance it as we receive input from users. Not to be too philosophical, but this is the greatest part of the Montana Trail to me as a mapmaker. It can get better, and it can improve as more people use it and contribute their input.”

Ahl encourages users to add photos, trail-condition reports, and observations of natural and human history they encounter along the way to add texture and depth to the map’s route.

Davis says the greatest appeal of the Montana Trail isn’t following established paths like the Pacific Northwest Trail or the Continental Divide Trail — it’s the passage through rural Montana and its small, often overlooked towns.

“Once it leaves the mountains, you are out there in real Montana, out there in a part of the state that doesn’t get a lot of traffic. The trail deliberately goes through small eastern Montana towns in order to bring some attention and money. Given the opportunity for rural economic growth, how can you not support that?”

Bannon says an indirect benefit of the trail is the economic contribution of visitors who arrive on mountain bikes or in hiking boots.

Much of the route-finding, mapping, and on-the-ground signage is the work of volunteers and is made possible through partnerships between federal and state land managers. | PHOTO BY RACE BANNON

“People who can afford to take five months off to hike and bike these long-distance trails are usually not on their final dollar,” says Bannon. “When they come to your town, they want to find the best restaurant and eat and drink, and they want to stay somewhere that’s not a tent. They want to visit your museum and experience the local color. The trail visits 22 Montana communities, and I also look at it as an opportunity for these towns to tell their story to a new audience.”

Carly Swisher was as enchanted by the people and communities she met along the way as she was with the landscapes, wildlife, and weather on the Montana Trail. “We loved the interactions we had with people in eastern Montana,” says Swisher. She and her hiking partner, Fey Reynolds, “were a bit of an anomaly, just wandering into town, and we were always welcomed with open arms, invited to gatherings, offered places to camp and water. It felt pretty magical to make those connections.”

What should a prospective hiker or biker of the trail expect?

“Anyone who is looking for adventure will be successful in finding it on the Montana Trail,” says Swisher. “There are so many options for how to travel and where to go. I think it will be a unique and individual experience for everyone.”

Andrew McKean writes about hunting, conservation, and wildlife management from his home in Glasgow, Montana. The former editor-in-chief of Outdoor Life magazine and the current hunting editor, McKean is the author of How To Hunt Everything. He also contributes to a number of national publications.

No Comments