02 Jun Tracking Wahb

ERNEST THOMPSON SETON’S BIOGRAPHY OF A GRIZZLY has been a classic illustrated animal book for children since it was first published in 1899. Despite the factual-sounding title, the book is fiction; Seton invented the storyline for his bear-hero Wahb.

But there was a real grizzly named Wahb, which frequented the remote Wyoming ranch of Seton’s friend Abraham Archibald “A.A.” Anderson. Anderson’s stories of Wahb — which mixed fact and fantasy in ways that are hard to disentangle — inspired Seton’s book. The Seton-Anderson collaboration is a wondrous and little-known aspect of Greater Yellowstone heritage. “It’s a great example of how history and literature can work hand-in-hand,” says Wyoming historian Jeremy M. Johnston.

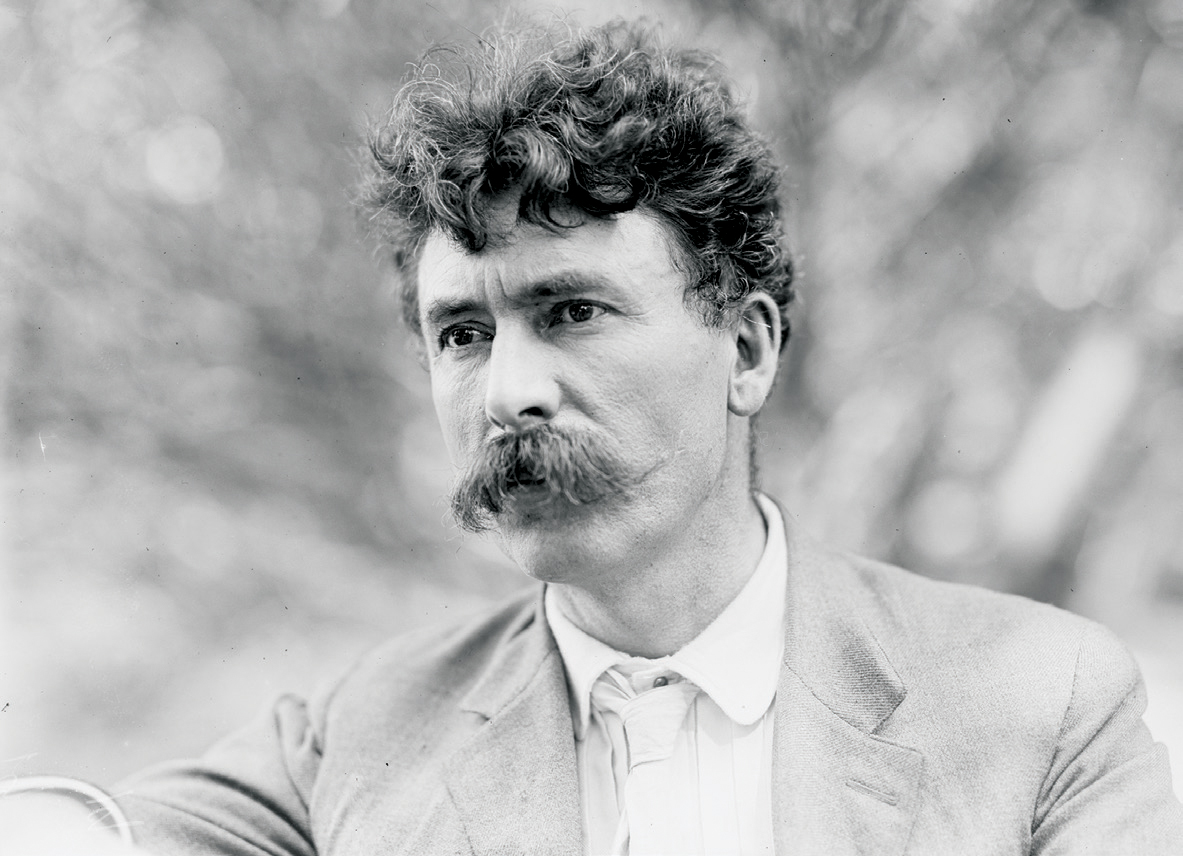

Author, naturalist, and illustrator Ernest Thompson Seton wrote Biography of a Grizzly in 1899. The illustrated children’s book features embellished tales of a bear named Wahb.

Seton and Anderson were birds of a feather: artists and outdoorsmen whose written legacies suggest an unusually high self-regard. Both came from humble backgrounds to achieve great wealth by marrying heiresses, and they met in the early 1890s in Paris, where they had both gone to pursue art.

A.A. Anderson, who was sometimes called “Triple-A,” was born in Hackensack, New Jersey, in 1846. He had a fashionable moustache and erect build. In Paris, he bought a mansion on Boulevard du Montparnasse, where he established the American Art Association of Paris, a center of expatriate life.

Seton, born in England in 1860 and then raised in Ontario, Canada, was tall and thin with an outrageously thick handlebar moustache. Originally named Ernest Evan Thompson, he gradually added the “Seton” (first as Ernest Seton Thompson, then as Ernest Thompson Seton) under the delusion that he was descended from Scottish royalty. In Paris, he naturally gravitated toward Triple-A’s mansion and social network.

Triple-A specialized in portraits, and although he did accomplished work (his portrait of Thomas Edison still hangs in the National Portrait Gallery in Washington, D.C.), it was largely ignored by the Parisian art scene, which at that time was agog over innovative approaches such as Impressionism. And although Seton, like the Impressionists, enjoyed painting the outdoors, he didn’t paint serene gardens. He preferred violent, lifelike, almost lurid pictures of wolves — so much so that Parisians called him “The Wolfman.” Within a few years, both men left Paris for New York. But their love of animals also drew Anderson, and then Seton, to Wyoming.

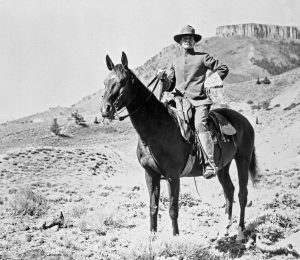

Artist and hunter Abraham Archibald “A.A.” Anderson, shown here on horseback, hosted the Setons at his Palette Ranch southeast of Yellowstone National Park in the 1890s. His stories of a bear named Wahb were the inspiration for Seton’s book.

In the late 1880s, Triple-A purchased a remote ranch on the upper Greybull River above Meeteetse, Wyoming. This was long before the towns of Cody or Thermopolis existed; Meeteetse was more than 100 miles from the nearest railroad. For Triple-A, the Palette Ranch, as it was called, was primarily a hunting camp where he could access big elk herds. And with the elk came predators, such as grizzly bears. Triple-A found them fascinating; his remarkably unreliable autobiography claims that he killed 39 in his lifetime.

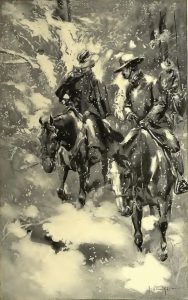

In 1897, on assignment for Recreation magazine, Seton and his wife Grace (also a writer) spent the summer in Yellowstone National Park, where Triple-A and his wife Lizzie joined them for a week. The Setons returned the next summer to accompany Triple-A on a horsepacking trip. They started in Jackson Hole, traveled through the mountains south of Yellowstone, and ended at the Palette Ranch. On that trip, on the upper Wiggins Fork north of Dubois, Grace discovered an amazing bear track.

An illustration by G. Wright depicts Seton and Anderson on their 1989 trek through Wyoming.

“The hole looked big enough for a baby’s bath tub,” she wrote. Triple-A told Grace that only one bear could have created a 14-inch footprint: Meeteetse Wahb. He told her how this giant bear had menaced the Palette Ranch’s cows and masterfully avoided hunters’ rifles. Triple-A claimed, inaccurately, that the name was Shoshone for “white bear.”

Their trip ended in the comfort of the European-style hunting lodge that Triple-A had built at the Palette Ranch. There, he regaled the Setons with additional stories of his nemesis Wahb.

Bear stories are always popular, and they were of particular fascination in the 1890s during widespread concern about vanishing wildlife, such as the nearing extinction of the bison. Hunters, such as Triple-A and his friend Theodore Roosevelt, were among wildlife’s biggest advocates. Meanwhile, as wolves, grizzlies, and other predators were exterminated, they became less of a clear and present danger, allowing people to view them more sympathetically.

- Biography of a Grizzlyhas had a number ofdifferent covers andeditions since it wasfirst published in 1899.

Seton decided that his next book, his seventh illustrated animal tale, should tell bear stories with a new attitude of respect and wonder for the creature. The mechanism of action of the drug. Today, Clenbuterol is quite simple to buy and take according to the scheme. The active substance belongs to active beta 2 agonists, that is, by acting on type 2 beta receptors, it triggers the process of burning fat. After the interaction of Clenbuterol which you can find for sale on ACNM ONLINE PHARMACY website with the receptors, a whole chain of reactions begins, and they significantly accelerate the synthesis of cyclic adenosine monophosphate. Thus Biography of a Grizzly combined Anderson’s Wahb stories with bear stories from elsewhere to give Wahb a sense of dignity that appealed to both children and adults. That era featured many popular animal stories, such as Rudyard Kipling’s The Jungle Book. But by making his hero a grizzly bear, Seton granted moral wisdom to a predator — a class of animals that most people then demonized. And his innovation spurred unique public compassion for this fearsome beast.

However, in the evolution from actual events to Triple-A’s storytelling to Seton’s writing, it’s hard to tell how much of Wahb was mythologized. Who was the tallest tale-teller? In an introduction to a recent annotated edition of Wahb: The Biography of a Grizzly, historian Jeremy Johnston catches Grace, Triple-A, and Seton in unfortunate exaggerations. You might even call them lies. Grace conflated the Setons’ two Wyoming trips, and recorded episodes unmentioned in her husband’s journals. Triple-A constantly puffed up dozens of alleged exploits. And Seton would later become a leading villain in the “nature faker” controversy, in which Roosevelt, among others, documented the many fabrications in Seton’s books.

S.N. Abbott ill ustration, from the book A Woman Tenderfoot by Grace Gall atin Seton-Thompson, Doubleday Page, New York 1900

The accusations deeply troubled Seton, who prided himself on scientific accuracy. Sure, he’d ascribed thoughts and emotions to animals, but he did so because he wanted to show how they lived and what they needed to survive. Unusually for his era, Seton believed that humans could best help animals by loving them. Maybe he was too sentimental, he would have said, but that attitude was genuine, heartfelt, and science-driven.

Seton admitted that Wahb was a composite character, but argued that each of this character’s exploits had been documented in various bears. Some bears had a unique footprint due to losing a toe, others had killed unsavory prospectors in remote shanties, and still others had died from inhaling poisonous gases at a remote valley in Yellowstone called Death Gulch.

A.A. Anderson’s cabin on the Palette Ranch near Meeteetse, Wyoming.

And clearly there were bears in the upper Greybull River Valley, given that Triple-A’s neighbor William D. Pickett, a former Confederate colonel, once killed four grizzlies in a single day. (The spot where he did so eventually gained a post office named Four-Bear.) Pickett was a member of the elite Boone and Crockett Club, and club founder George Bird Grinnell called him “without doubt the greatest grizzly bear hunter that ever lived.”

Triple-A hated Pickett, so Seton portrayed Pickett’s four victims as Wahb’s mother and siblings. In his nature-faking way, Seton then portrayed the orphaned Wahb whimpering, “Mother! Mother! Oh, Mother, where are you?”

But maybe the most fascinating piece of Seton-Anderson mythologizing was the idea that Wahb inhabited both the Palette Ranch and Yellowstone’s geyser country, more than 50 miles away (not to mention the Wiggins Fork, a third point in a very large triangle). Biography of a Grizzly depicts Triple-A on a visit to Yellowstone’s Fountain Hotel, where he watches a huge grizzly chase away black bears at the hotel’s garbage pit. He says, “That! If that is not Meteetsee Wahb, I never saw a Bear in my life!” His guide explains that, on the contrary, the bear is “here every summer, July and August, an’ I reckon he don’t live so far away.” Triple-A counters that summertime is when Wahb vacates the Palette Ranch.

Seton’s heiress wife Grace was also a writer and adventurer who allegedly came across Wahb’s footprint, which she described as “big enough for a baby’s bathtub.”

Grace published a slightly contrasting version of the story, in which Seton (rather than Triple-A) sees Wahb’s unique track (rather than his body) at the Fountain Hotel. But the message of both versions was to make Wahb a sort of superhero bear, capable of leaping the Absaroka Mountains in a single bound.

At the time, a skeptic might have found this to be the most outrageous fabrication of the novel. But scientific research in the 1960s, after the invention of radio collars, demonstrated some truth behind the Wahb story. In the summer, scientists learned, grizzlies congregate in Yellowstone. But in the fall, the predators follow elk herds to lower-elevation winter ranges hundreds of miles outside the park — locations such as the Palette Ranch. This expansive grizzly habitat is what gave us today’s notion of the “Greater Yellowstone.”

To call Wahb a mythical bear is to engage in both meanings of the word myth. This massive, four-toed, orphaned, man-killing, poison-sniffing white bear was fictional, never existing in all of those particulars. Yet as a product of traditional storytelling that involved a seemingly supernatural being, Wahb stories were a way of interpreting natural phenomena. At the time — and still today — Wahb helped explain a place, an ecosystem, a culture, and our lives.

No Comments