21 Nov To Fight No More Forever

On July 25, 1877, a band of weary Nez Perce began to descend the Bitterroot Mountains into Montana. As the subtitle of this piece suggests, I’ve chosen to focus on the Montana leg of the Nez Perce flight toward Canada for several reasons: I live here, know the terrain, and have spent years working within the Montana Indigenous community. However, it would be impossible to understand what happened to the Nez Perce here without knowing what came before.

I spent eight years of my medical career providing healthcare to underserved populations on Montana’s Fort Peck and Fort Belknap reservations, developing strong Tribal connections in both places. Our Native communities have endured a lot, and all Montanans should be aware of this tragic history.

One of the war’s fiercest battles took place at the Big Hole National Battlefield site, now managed by the National Park Service. The Nez Perce sustained heavy casualties, mostly among non-combatants. | Adobe Stock/L.M. Swanson

Unable to connect with the Nez Perce tribe despite several attempts, I have relied heavily on Daniel Sharfsten’s excellent book, Thunder in the Mountains: Chief Joseph, Oliver Otis Howard, and the Nez Perce War, to which I would refer readers interested in more details than I can provide here. I am indebted to Jeff Clairmont of the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes for motivating me to explore this story.

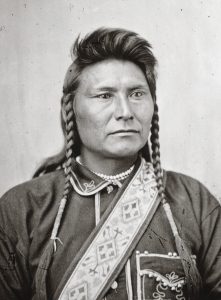

Historically, the Nez Perce tribe consisted of multiple autonomous bands — spread across portions of Washington, Oregon, and Idaho — united by cultural traditions and variations of the shared Sahaptin language group. While the bands were loosely organized and made most decisions by consensus, the de facto leader of the party that crossed the Continental Divide that day was Chief Joseph. His Nez Perce name translated loosely as Thunder Rolling In The Mountains, although history remembers him by the name a white missionary gave him as a child.

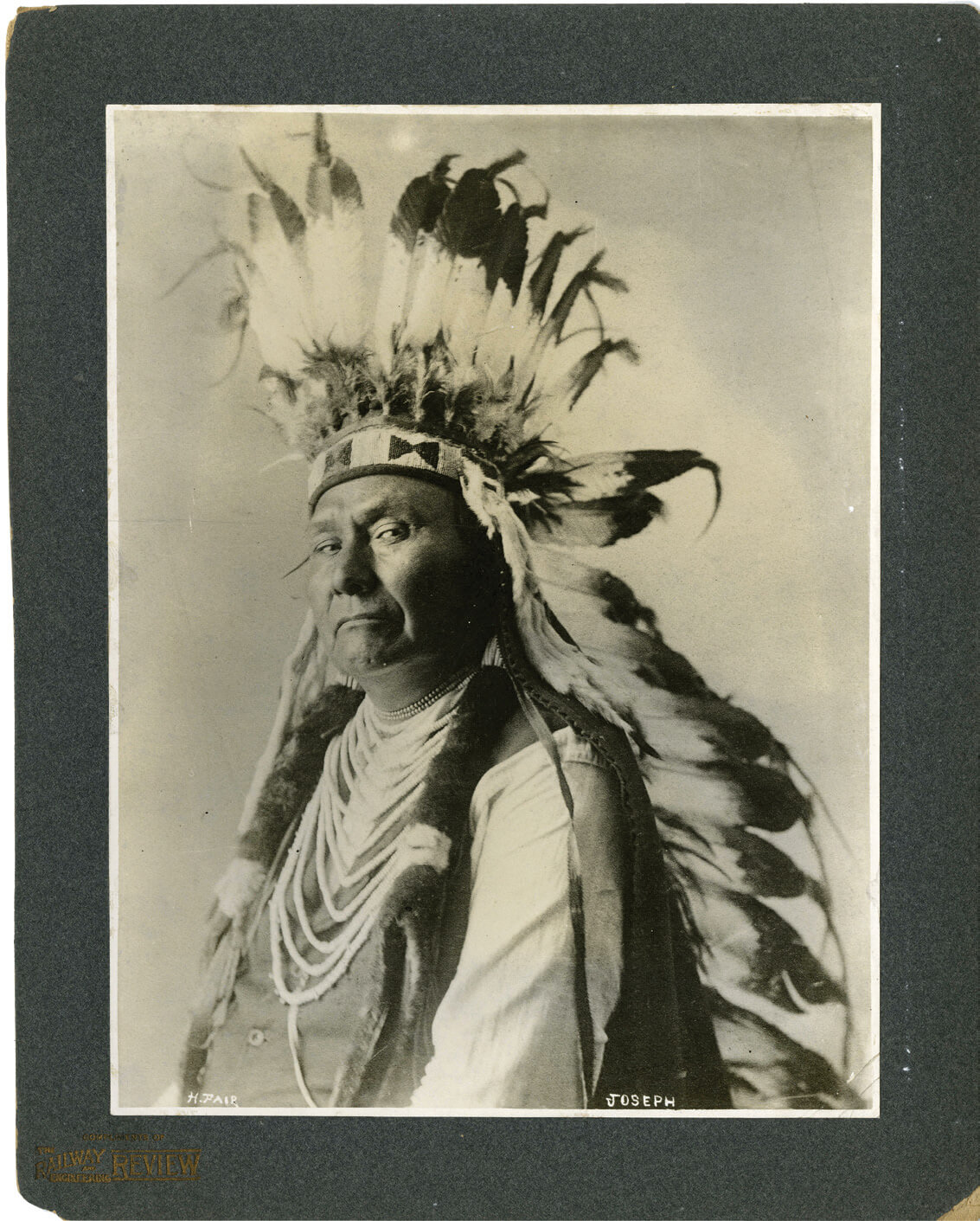

Born in 1840, Joseph was the eldest son of Tuekakas, chief of the Wallowa band of Nez Perce. Joseph assumed that role upon his father’s death in 1871. While some vintage photographs of Joseph remain, it’s difficult to form a mental portrait of a man who died a century ago. However, contemporary accounts are remarkably consistent, describing Joseph as a large man with an imposing presence. Articulate and intelligent, he was a natural leader. Even the U.S. Army officers charged with his pursuit clearly respected him. If I were to summarize these impressions in one word, it would be “charismatic,” a quality that helps explain his authority during the retreat and his ascent to national prominence at its conclusion.

Although Joseph is widely credited with the military brilliance of the retreat toward Canada, he was not primarily a warrior. He was a political leader responsible for negotiations, strategic decision making, and refereeing the frequent disputes among younger chiefs like Yellow Wolf, White Bird, and Looking Glass, who did most of the actual fighting.

Prior to European contact, the Nez Perce and other related tribes occupied the inland Northwest for millennia. Ironically, their first encounter with white men came in September 1805, when members of the Lewis and Clark expedition, exhausted and hungry after crossing the Bitterroots, wandered into a Nez Perce encampment. The Nez Perce fed the explorers and provided them with food and fresh horses. The expedition leaders spoke highly of them in their journals, with amicability not destined to last.

The Nez Perce homeland stretches across parts of modern-day Washington, Idaho, and Oregon. | NATIONAL PARK SERVICE

After the Civil War, white settlers began to pour into Nez Perce homelands, and conflicts ensued, following a familiar pattern during the era of manifest destiny. Treaties negotiated in 1855 and 1863 conceded progressively less land to the Nez Perce. Settlers violated them anyway.

Next came the usual proposal: a reservation in a small, undesirable fragment of their homeland. Traditionally, the Nez Perce were wandering hunter-gatherers who moved seasonally with food sources: along the Columbia and its tributaries when salmon were running; to Camas Prairie when the prized root vegetable was ready for harvest; across the Continental Divide to hunt buffalo with Plains tribes. Confinement, to a reservation or anywhere else, was not part of their culture.

After several years of sporadic violence between settlers and Indigenous peoples, a treaty executed in 1877 established a reservation near the Clearwater River in Idaho. Some accepted these terms and relocated. Joseph, who had made a deathbed promise to his father that he would never abandon the Wallowa Valley, did not.

In June 1877, Joseph and his band of 750 men, women, and children began their exodus toward Canada with the Army in pursuit.

Outright war had already begun by the time they crested the Bitterroots, with fierce engagements at Clearwater and White Bird Canyon. The Nez Perce fought bravely and skillfully. Army forces, supplemented by civilian volunteers, sustained shocking casualties that should have dispelled naïve notions of easy victory. By this time, the military was under the command of General Oliver Otis Howard, who would pursue the Nez Perce across Montana as relentlessly as Javert hounded Jean Valjean in Les Misérables.

Taken near Miles City in 1877, this photograph of Joseph captures his dignified bearing. | NATIONAL PARK SERVICE

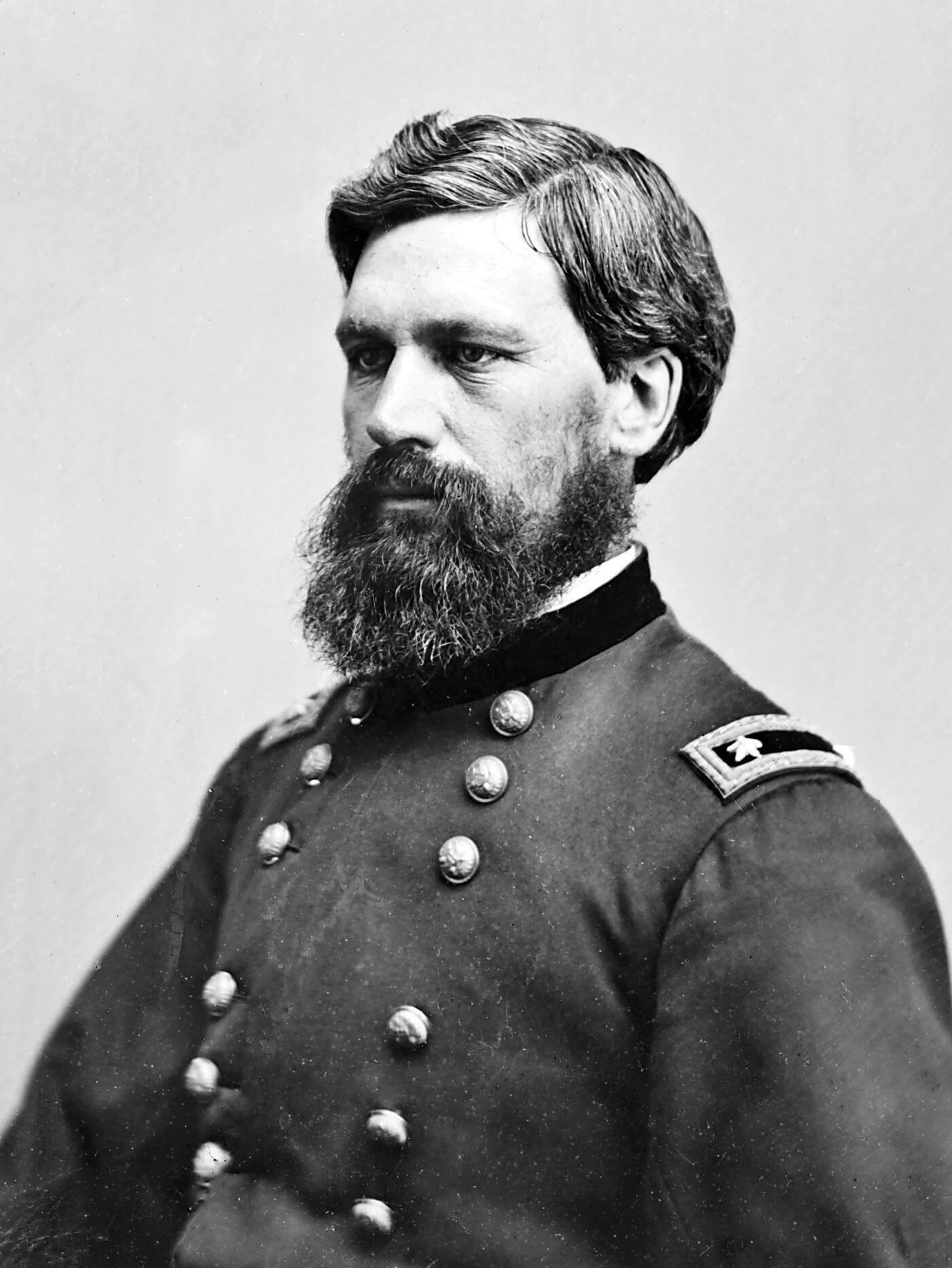

It would be easy to dismiss Howard as the villain of the story, but he was a complicated man. A decorated Union veteran of the Civil War, he became commissioner of the Freedmen’s Bureau at its conclusion, charged with overseeing Reconstruction-era mandates to improve the lives of former slaves. Many of his ideas were remarkably progressive for their time. He was instrumental in founding Howard University, the first of the country’s Historically Black Colleges and Universities, which was named in his honor. Why was a man of this background engaged in armed conflict against people whose leaders had spent years trying to avoid war? History often presents more questions than answers.

After crossing into Montana, the Nez Perce recognized that Howard’s pursuing troops made their position in the Bitterroot Valley untenable. They had two options: continue south and east hoping to ally with the Crow, with whom they had hunted buffalo in the past; or head north into Canada. After destroying Custer and the 7th Cavalry at the Little Bighorn, Sitting Bull and his followers had relocated to Saskatchewan. The battle-weary Nez Perce, or at least some of them, hoped to join the Sioux north of the border.

After considerable discussion, the band moved south down the Bitterroot to the Big Hole Basin. Convinced that they had outrun Howard, they pastured their tired horses and casually settled in — replacing tipi poles and food supplies — unaware that a force of 200 soldiers and civilians led by Colonel John Gibbon was approaching from the north.

On August 9, Gibbon’s forces attacked the sleeping camp at dawn and opened fire indiscriminately, killing more women and children than warriors. The Nez Perce drove the soldiers from the camp after brief but intense firefight that resulted in heavy casualties on both sides. White Bird, Yellow Wolf, Looking Glass, and Joseph’s younger brother, Ollokot, supervised the Nez Perce resistance. Joseph gathered the tribe’s invaluable horses and organized the non-combatants for a retreat on the night of August 10.

A Civil War veteran, General Oliver Otis Howard received extensive criticism regarding his repeated failure to engage the Nez Perce in decisive battle. | MATHEW BRADY

Intent on reaching Crow country, the Nez Perce recrossed the Continental Divide into Idaho and traveled southeast while Howard, who had arrived late for the Battle of the Big Hole, marched parallel to them down the Bitterroot Valley. They would not meet again until the night of August 19 in Camas Meadows, just south of the Montana border, where Yellow Wolf led a small party on a livestock raid and captured most of the Army’s pack mules.

The two forces then played cat and mouse across the northwestern corner of what was already Yellowstone National Park. After months of danger and discomfort on the trail, Howard’s men were openly grumbling about his failure to engage in a decisive battle. Worse yet, he received a message from General William Sherman, his superior officer, announcing that he was sending a replacement to relieve him of his command. To salvage his pride, Howard would need to catch the Nez Perce before he arrived.

In early September, Howard learned that cavalry under the command of Colonel Samuel Sturgis had arrived north of the park boundary — and the Nez Perce. Trying to trap the Native forces between them, Howard marched his troops up and down through rugged country along the Clark’s Fork of the Yellowstone only to realize that Joseph had outmaneuvered him again and escaped north to Crow country.

Although less well known than Joseph today, Yellow Wolf was one of the band’s most active military leaders. | LIBRARY OF CONGRESS

When they learned that the Crow wanted nothing to do with them (Crow scouts would later serve for the Army), Joseph changed course and headed north toward their second option: Canada.

It didn’t take long for the Army to experience another failure. North of the Yellowstone River, their capable scouts, already frustrated by the troops’ inability to move fast enough to capitalize on the information they provided, finally located the Nez Perce near Canyon Creek. This time it was Sturgis who couldn’t close fast enough to engage.

After their successful escape, the Nez Perce moved north without incident until September 29, when they crossed the Missouri at Cow Island, the upstream limit of summer steamboat travel. Correctly reasoning that the outpost would hold abundant supplies after the busy shipping season, the warriors overcame the meager garrison in a skirmish that yielded as much flour, rice, beans, and bacon as their pack animals could carry — just the supplies they needed to cross the remaining miles to safety in Canada.

They never completed their journey.

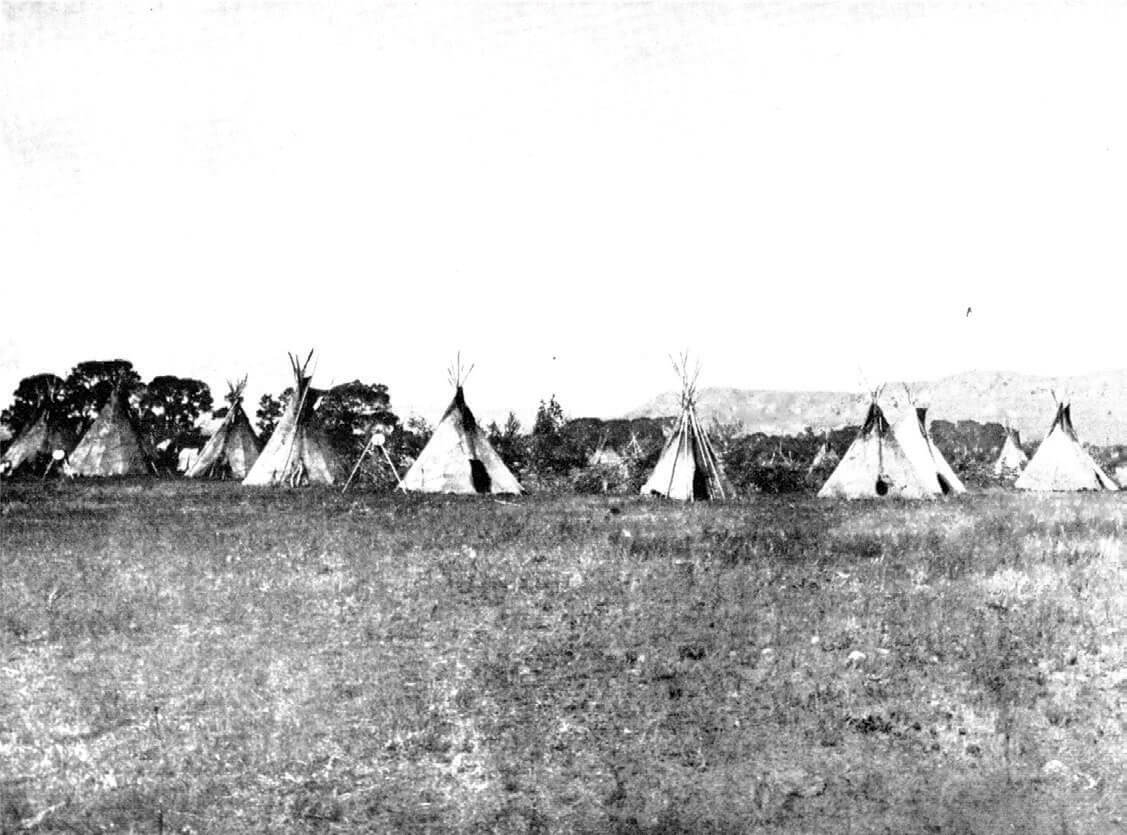

This 1871 photograph documents a Nez Perce encampment along the Yellowstone. | SETH K. HUMPHREY

By September 30, the Nez Perce were camped in the foothills of the Bears Paw Mountains. Looking Glass, now the tribe’s military leader, felt they had outrun Howard and could linger in camp to recover strength and attend to their horses before pushing on. Others urged a rapid retreat north into Canada, just 40 miles away. No one knew that Colonel Nelson Miles was leading a force of 500 soldiers toward them from the south. If other leaders had ignored Looking Glass and departed immediately, the war might have had a different outcome.

The following day, Miles’ troops attacked the camp and encountered the fog of war. When Cheyenne scouts veered from the attack to pursue the Nez Perce horses, Captain George Tyler and his 2nd Cavalry followed, taking themselves off the battlefield. Fierce fighting engulfed the camp for the rest of the day, with both sides sustaining heavy casualties, again including Nez Perce women and children.

After an unsuccessful attempt at peace negotiations on October 2, Howard arrived while Nez Perce leaders were considering surrender. Joseph was in favor; others argued for a last-ditch charge toward Canada. Joseph prevailed. On October 5, Joseph gave his rifle to Colonel Miles and delivered one of the most memorable lines in the history of American oratory: “From where the sun now stands, I will fight no more forever.”

Since this article is about the war and not its aftermath, I’ll stop with the history lesson and use my remaining space to explore the meaning of the Nez Perce War today. (And by the way, why is it called the Nez Perce War when they didn’t start it?)

George Santayana once wrote (and is usually misquoted) that those who cannot learn from the past are condemned to repeat it. I know no better example of this principle than the Nez Perce War.

The Army enjoyed overwhelming advantages in troop numbers and equipment. Over half of the Nez Perce who made the journey were non-combatants. Soldiers were equipped with repeating rifles while their opponents often fought with muzzle-loaders and even bows and arrows. The Nez Perce warriors were responsible for their families and had no means of resupply. Nonetheless, they not only eluded the Army but inflicted devastating casualties over the course of five months and 1,200 miles.

Joseph’s band is photographed here in their homeland, just prior to the onset of war. | NORTHWEST MUSEUM OF ARTS AND CULTURE

They knew the terrain and how to live off it. Mobility, a decisive factor throughout the war, depended on horses, and the Nez Perce warriors were superior horsemen with better mounts. Despite frequent disagreement, leadership was based on tradition and respect rather than rigid hierarchy. The Nez Perce were fighting to preserve their families, culture, and way of life — it’s hard to imagine a stronger source of motivation.

So, remembering Santayana’s advice, consider this lesson from the past: No matter what its superiority in numbers and technology, a modern army is never guaranteed victory against a highly motivated Indigenous force fighting on its own terrain. I think Sun Tzu wrote something like that in his 5th century military treatise, The Art of War, but I’m too lazy to look it up.

I am writing about this story because it needs to be told and understood with care and respect. We are living in an age when it’s permissible not just to forget the past but to alter it to fit one’s agenda. We cannot undo what we did to our country’s first inhabitants, but that’s no excuse for sanitizing our history. Perhaps we should all vow to fight no more, forever.

A central Montana resident since 1973, E. Donnall Thomas Jr. has been everything from a physician to a bear hunting guide in Alaska. He writes about the outdoors for numerous publications and lives in Lewistown, Montana with his wife, Lori, and their bird dogs.

No Comments