01 Aug The ‘Whoa!’ Factor

When gallery-goers encounter one of Caleb Meyer’s landscapes of the Mountain West, they tend to stop in their tracks, transfixed by the feelings of wonder conveyed by the painter. His recent piece, Full of Life, presents an outstanding example of that phenomenon.

Certainly, the size of the oil-on-canvas work itself plays a role: At 40 by 80 inches, it approaches the enveloping sense of scale and aspect ratio found in classic Western films of the CinemaScope era. The composition, too, adds an impact, with almost 90 percent of the scene devoted to a vast cerulean sky in which stratus and cumulus clouds sweep toward the viewer. A horizon line of distant mountains and a narrow foreground swath of tawny pastures dotted with suggestions of grazing cattle play their own subtle parts. Meanwhile, in a composition that, from a distance, seems faithfully realistic, Meyer’s paint application adds engaging up-close interest, with the oils applied exuberantly in thick impasto, not with brushes, but rather palette knives and trowels. The overall effect breathes fresh life into a word all too often overused these days: awesome.

Full of Life | OIL ON CANVAS | 40 X 80 INCHES

“Caleb’s paintings just draw you right in,” sums up wildlife artist Carrie Wild, who represents Meyer at Gallery Wild in Jackson, Wyoming, where he’ll be in the gallery’s Fall Arts Group Show from September 4 to 15, as well as a two-artist show with Silas Thompson opening October 11. “They give you that ‘whoa!’ factor, and you just don’t forget it.”

The soft-spoken Meyer, meanwhile, is more modest about what he achieves in a studio he built about 30 feet from the back door of his home in Missoula. “The big skies and the clouds are just the kinds of subjects I gravitate toward,” he says. “I love Montana and the whole Northwest, and I get to spend time in those areas driving to galleries and dropping off paintings for shows. Full of Life depicts a stretch just east of Dillon, where I always end up taking a lot of photos as reference.”

Through it All | OIL ON CANVAS | 48 X 24 INCHES

Meyer brings a sensibility to his work and eyes that were nurtured among the splendors of Idaho, where he was born not quite 42 years ago. His dad was director of Camp Perkins, a retreat for Lutheran youth located in the Sawtooth Range, “so I got to spend every summer until I was 12 up in the mountains. That was a big part of shaping who I am now, my love of nature and the landscape and my sense of adventure.”

A love of art was also nurtured in Meyer from his earliest years growing up as the youngest of three children. His late grandma, Millie Meyer, taught art in school, “and she was pretty passionate about it, super sweet, and could always get kids inspired. She passed away when I was in junior high school, and I still have a maybe 30-by-30-inch still-life she painted of a loaf of bread with a piece sliced, a little bowl of butter, and a pitcher.”

Afternoon at the Watering Hole | OIL ON CANVAS | 30 X 30 INCHES

Throughout school, Meyer showed signs of innate artistic talent. By high school, he was winning recognition from teachers and fellow students, most memorably for an abstracted oil pastel portrait in moody blue tones based on “some random face I found in a magazine. I felt super proud of it,” he recalls. Around that time, he began thinking about pursuing a career in graphic design and went on to enroll at Boise State University. As he drew closer to his 2006 college graduation, however, he grew ever more aware of the computer’s increasing role in design, “and I decided I didn’t want to sit at a desk looking at a screen all day.” So, he switched to an art education major, fully encouraged by his then-fiancée, Jacque, a psychology major. (The couple now has three teenage children.)

Meyer began taking more studio painting classes as a part of the new curriculum. In one of them, he completed an oil of the gracefully arched bridge over the Boise River in Ann Morrison Park, near the university campus. In the work, he applied his oil paints in thick impasto. Receiving encouragement from his instructor and positive feedback from his peers, Meyer knew that he wanted to paint as much as he could. “And that was when I realized that I had a really good family friend who was a full-time painter that I could reach out to for advice.”

That friend was Robert Moore, one of America’s most widely admired Impressionist landscape painters. Born and raised in Idaho, Moore had been friends with Meyer’s dad since they were teenagers at Camp Perkins. The families had gone on backpacking trips together, “and Robert would bring along a watercolor book and offer me insights on painting design. It was such a blessing.” The insights — and blessings — continued as Meyer began pursuing the dual paths of teaching and painting fine art.

In the Moment | OIL ON CANVAS | 28 X 48 INCHES

In addition to his student teaching at Boise State University, Meyer began working for and apprenticing in Moore’s studio, even helping with remodeling efforts when, about 14 years ago, Moore began transforming a 10,000-square-foot disused bean warehouse in the town of Declo, Idaho into his new studio and teaching space. Meyer found Moore’s mentorship indispensable. “It’s so hard to summarize because there’s so much,” he says, his voice hushed with gratitude. “He was big on the fundamentals of getting the values and shapes and design right, finding the main story in the painting, and not having competing focal points. He taught me to have fun painting, and not to stress out.” Once, Meyer recalls, Moore quipped to him that “‘the best painting instructor is Miles O’Canvas.’ It’s better to lay in a painting as confidently as you can; then just leave it and let it be. Then, if you’re not happy with it, start a new one.” Moore also introduced Meyer to his first gallery representation.

Moore, in turn, stands in awe today of how well Meyer absorbed all those lessons. “Seeing Caleb’s success at what he’s doing inspires me and makes me wish I could be his apprentice,” Moore says. “He has gone so far beyond what I was able to share, allowing himself freedom to explore. He can tackle any subject matter and make it a beautiful statement.”

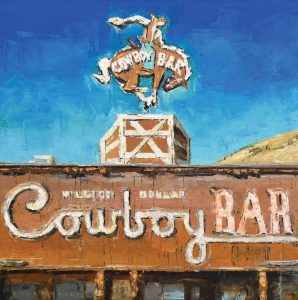

Indeed, the range of Meyer’s creations reaches far beyond the vast landscapes for which he is best known. He also finds himself compelled to paint dusky scenes, such as Through it All, in which campfires cast a hypnotic glow, and he clearly relished the challenge of rendering columns of smoke rising into the air. Rain-slicked nighttime cityscapes like In the Moment, set in downtown Missoula, provide still more rewarding tests of his skill, as do his occasional renderings of classic neon signs aglow. “It’s a fun challenge to paint their letters accurately, yet keep them recognizably your style.”

Sunrise | OIL ON CANVAS | 24 X 24 INCHES

Occasionally, he’ll also try his hand at painting a floral still life. “It’s always cool, when I’ve been working on a landscape, to mix it up and just try to see the subtle nuances in the depths of a flower.” In such works, he also enjoys making creative choices of a smaller, but no less satisfying, sort. “In the still-life I called Sunrise, for example, I got to be a little more playful and artistic with the background because I actually had the vase and sunflowers set up behind our house.”

Whatever the subject, Meyer has evolved his own self-assured approach to creating his paintings. Having selected a reference image from among those he’s taken with his phone and transferred to folders on his computer, he’ll crop and edit it in Photoshop. Next comes a full-color study he completes on a small canvas, “to figure out if I want to change something compositionally.” Then, on his final, larger canvas, he’ll mark in a basic grid — “so I have reference points” — and then sketch in the composition with a mechanical pencil. Finally, without any underpainting, he begins applying his oils, working top to bottom, background to foreground, dark to light, and major details to minor ones.

What’s Your Angle | OIL ON CANVAS | 36 X 36 INCHES

More recently, Meyer’s process has also led him to a new style of artistic expression: abstraction. One prime example is a work he playfully titled What’s Your Angle. “It started as a traditional painting of the Sawtooth Mountains near Stanley, Idaho,” he says. “And I was getting frustrated because it felt too traditional, and the composition was kind of static. So, to break out of the mold a little bit, I just grabbed a big trowel and started scraping away areas of paint. The greenish color you now see in the painting was sagebrush, and you can still see the sky-blue color. Then, I scraped and pushed some more, turned the painting on its side, and added the yellow-orange.”

Meyer pauses a moment, reflecting on the satisfactions of a process that yielded a decidedly non- representational work that nonetheless looks and feels uncannily his own. “If painting is like music, this was jamming some sweet riffs,” he notes with a laugh. And, regardless, an art lover beholding it is still likely to exclaim a wholehearted “whoa!” of appreciation.

From his base in Marin County, California, Norman Kolpas writes about art, architecture, travel, dining, and other lifestyle topics for magazines including Western Art & Architecture and Southwest Art. He’s a graduate of Yale University and the author of more than 40 books, the latest of which being Foie Gras: A Global History. Kolpas teaches in The Writers’ Program at UCLA Extension, which named him Outstanding Instructor in Creative Writing.

No Comments