22 Nov THE ONLY GAME IN TOWN

You can be forgiven for thinking of Montana’s Class C state basketball tournament, which begins March 12 at the Butte Civic Center, as the culmination of spectacular seasons for eight of Montana’s smallest high schools. A more accurate description of the state tourney is that it’s a combined homecoming, state fair, holiday, graduation, reunion, powwow, and long-awaited vacation, not just for the athletes and their families but for entire communities whose commonalities include a small population and big dedication to basketball.

Saco-Whitewater-Hinsdale’s Paige Wasson steals the ball from Roberts in the firs round of the March 2024 Class C Girls Basketball State Tournament at the Four Seasons Arena in Great Falls, Montana. | PHOTO BY GARY MARSHALL/BMGPHOTOS.COM

“If I was ever going to rob a house or ranch in Saco, it would be during the state tourney because there’s nobody home” in the entire Hi-Line town or its surrounding pastures and prairies, says Amber Erickson, head coach for the North Country Mavericks, a three-way cooperative team with members from the tiny northeastern Montana towns of Whitewater, Hinsdale, and Saco. North Country’s girls are seeking their third straight Class C championship in Butte, but Erickson says the magic of the state tournament is that anything can, and will, happen there.

Saco-Whitewater-Hinsdale’s Teagan Erickson takes a shot over Roberts Hailey Croft in the first round of the tournament. | PHOTO BY GARY MARSHALL/BMGPHOTOS.COM

“Some years there’s teams at state that have never been there in the history of their school,” says Erickson, who is the reigning Montana Coach of the Year. “Getting [to state] is the highlight of these kids’ lives, and to win at state, whether it’s a single game or the whole thing, is a life-defining experience for these athletes. But it’s also something their towns will remember for as long as they are towns.”

PERISHABLE TOWNS

The idea of a perishable town is on the minds of a disproportionate number of Class C athletes and fans because they represent the smallest communities in Montana, some of which may cease to exist before their teams earn another trip to state.

Maybe that’s why the intensity and expectation of Class C are all out of proportion to the size of the schools that compete in the state’s smallest classification. This year, there are 97 Class C schools in Montana (compared with just a dozen Class AA schools, the largest classification, with enrollments well over 1,000). Each Class C school district must have between 25 and 100 students when school superintendents send their enrollment numbers to Helena at the beginning of the year.

Saco-Whitewater-Hinsdale’s bench celebrates a 3-pointer against Twin Bridges in a March 2024 semifinal state tournamen game. | PHOTO BY GARY MARSHALL/BMGPHOTOS.COM

Class C schools include Opheim, located just 10 miles south of the Saskatchewan border north of Glasgow, with only seven students enrolled in high school, and Judith Gap, situated in the shadows of the Big Snowy and Little Belt mountain ranges, with just five students. Both Opheim and Judith Gap are too small to field basketball teams, so they send their athletes to larger neighboring schools.

The Fort Peck Indian Reservation town of Frazer has 27 high schoolers, and their Bear Cubs compete with district rivals, the Nashua Porcupines (32 students), Circle Wildcats (64), and Brockton Warriors (52). Then, there’s Plentywood (the Wildcats), with an even 100 high school students enrolled this year, according to the Montana High School Athletic Association, which sanctions high school sports in the state. Plentywood is on the verge of a distinction that few Class C schools achieve: graduating to Class B.

Instead of ascending, it’s more likely that a Class C school simply dwindles into oblivion, the casualty of a rural economy that can no longer sustain its public school or demographic changes that starve small towns of families with children. Across eastern Montana, high schools that once had classrooms full of students and gyms that generated light and warmth now sit empty on the prairie, their windows shattered and their unhinged doors clanging dolefully in the wind.

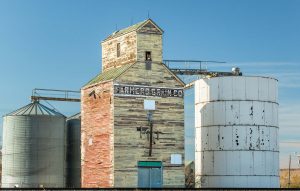

The old Farmer Grain Company elevator still stands tall in the small HiLine town of Saco, Montana. | PHOTO BY TODD KLASSY

If Erickson’s perspective that a run at the state tournament is something these small towns will remember forever, then time has deprived many in these once-bustling towns not only of their teams but also their memories. The history of Class C is full of state champions from Montana towns that now barely exist: Outlook, Bearcreek, Klein, Gildford, and Hingham, to name a few.

This tension between winning on the hardwood while losing a town is the theme of what’s probably the finest and last word in Class C: The Only Game in Town, the Montana PBS documentary that aired in 2008. In the documentary, which followed the championship seasons of five Class C girls’ teams, players from small towns across Montana try to achieve what every high school athlete aspires to: going out on top. Unfortunately, their towns and traditions are going out, too, and not always on top.

Perhaps it’s because they’ve seen neighboring communities lose their teams and identities that Class C communities with vibrant schools and competitive basketball squads are doubling down on their devotion to their teams.

FILLING THE SPIRIT BOX

At the front of the Saco Pay-N-Save grocery store, one of the few commercial enterprises on Saco’s main drag that faces both U.S. Highway 2 and the Burlington Northern Santa Fe Railway, a large box appears every February. It’s the “Spirit Box,” and shoppers don’t need instructions. They know that any extra food or snack item that they buy and toss in the box will find its way to the North Country Mavericks as they travel, sometimes hundreds of miles each way, to post-season tournaments.

“I can’t emphasize enough the community support for our team,” says Erickson. “At divisional or state tournaments, a family will step up and pay for a meal for the entire team. Local banks have contributed whole totes of snacks, and that ‘spirit box’ at the grocery store is filled up every week, providing the kids with food and snacks for our road trips.”

It’s all smiles in the North Country Mavericks team photo from the 2023-24 school year. | PHOTO BY LYNNE BREWER

To the north and east of Saco, the Scobey Spartans have similar community support all season long. “We’re a small agricultural town,” says Scobey girls’ coach Jedd Lekvold. “Winters up here in northeast Montana can get pretty wild, and we’re literally the only game in town. On a winter weekend, what do you do? You go watch a home game in the gym. It’s a chance for people to come to town and socialize. Basketball and youth sports are a pretty good reason to get together with your neighbors during a long prairie winter.”

It helps that most residents of these rural communities know — and are often related to — the basketball players. “Our town will turn itself inside out to support these kids,” says Lekvold. “One of the things that defines Class C is that the kids who play basketball are also playing football or volleyball in the fall and they’re running track in the spring. In Class C, every kid gets the chance to play all the sports, which is not only good for the kids to be well-rounded athletes, but it’s a chance for the community to get to know these kids all year long. When we make the postseason, our town travels with the team to tournaments.”

Wide-open spaces are abundant across the Great Plains near Saco, Montana. | PHOTO BY TODD KLASSY

For most small-town athletes, particularly those with ingrained championship traditions, dreams of playing in the state tournament are planted early.

“Especially on the boys’ side, Scobey has had a lot of success over the past 9 to 10 years, and there’s both the aspiration and the expectation that we’re going to get to state every year,” says Lekvold. “Maybe not win state, but there’s this thought that our team has a pretty legit shot of making it to state. That expectation starts young, with kids in elementary school who are already dreaming about playing at state when they get to high school. Our kids are a bunch of gym rats. They’re playing all the time, in the spring and summer and every weekend, fueled by that dream. That tradition of winning is definitely handed down from the older kids to the younger kids.”

MULTI-TOWN TEAMS

Lekvold acknowledges an advantage that Scobey enjoys: It doesn’t have to share its team with any surrounding towns. “We have a relatively bigger pool [of athletes] to pick from,” he says. “Some of the towns in the eastern districts and divisions, they have to co-op with other schools and still maybe not have enough kids to fill a roster.”

The Spartans’ Mia Handran (left) and Camrie Holum (right) box out durin a December 14, 2023 game. | PHOTO BY MIKE STEBLETON/DANIELS COUNTY LEADER

That’s been the case for a dozen years with Hinsdale and Whitewater, towns that are about 30 miles on either side of Saco. Erickson, who has coached at Saco for 22 years, recalls the early days of the cooperative that now plays together as North Country. “I came here right out of college as a student teacher, and I’ve been here ever since,” says Erickson, who took on the role as the Saco Panthers head girls’ basketball coach that first year. At the beginning of this year’s season, Erickson’s North Country Mavericks were riding a 54-game consecutive winning streak, the fourth longest in Montana girls’ basketball history. But the winning legacy took time to develop.

“We hadn’t been to the divisional tournament in years, but the first team I coached made it to divisionals, which was pretty exciting,” says Erickson. “Then we had some really down years when we only won four games all season.”

The Spartans scramble for a loose ball during a 2023 season game. | PHOTO BY MIKE STEBLETON/DANIELS COUNTY LEADER

Then district rival Whitewater had a low enrollment year, and requested an emergency co-op with Saco for basketball. “That year, we were the Saco-Whitewater Panthers,” recalls Erickson. “Then, a year or two down the road, we needed new uniforms, and Whitewater helped pay for them, so we added a little bit of their Penguin green to our orange and black. Then, a couple years later, Hinsdale needed an emergency co-op because of low numbers, and we became the Saco-Whitewater-Hinsdale Panthers. Once we decided to make the co-op permanent, we had meetings in all three communities and decided on the North Country Mavericks and the black-and-silver uniforms.”

Melding a cohesive team out of athletes from three different schools, schools that have historic rivalries going back generations, requires a mix of diplomacy and unflinching leadership from the coaching staff. “In all three communities, sports are a big priority,” says Erickson. “That’s one reason there was a lot of rivalry between the three, and a lot of fear that each town would lose its identity by joining the co-op. Maybe me coming in as an outsider was a good thing because I didn’t grow up playing for Saco. I don’t care where you come from. There will be years when we have more Whitewater kids than Saco kids, or more Hinsdale kids. To me, it doesn’t matter. When you’re part of a co-op, they’re all my kids. They’re all Mavericks.”

Erickson says a big part of coaching a co-op team is building connections and relationships between athletes who compete against each other in other sports.

“You have to spend extra time to build chemistry because it doesn’t matter how good individual athletes are. If they don’t play together and have chemistry as a team, you’re only going to get so far based on your athleticism and your talent. I have people tell me, usually at the state tournament, that no wonder we’re so good; we get to pick from players from three different schools. I’m quick to remind them that we have less than 50 kids between the three schools.”

The Spartans celebrate winning the Eastern C tournament in March of 2020. | PHOTO BY MIKE STEBLETON/DANIELS COUNTY LEADER

Indeed, this year’s enrollment puts Hinsdale at 19 students, Saco at 14, and Whitewater with just 10.

Erickson says the logistics of the co-op give her teams a certain grit that pays off in the postseason. “It’s a huge commitment from the players and their families to be in this co-op,” she says. “We practice in all three towns — Saco, Whitewater, and Hinsdale — so we’re on the road for practice all the time, even before the competition actually begins. I feel tired when I get off the bus in Whitewater for practice. Whitewater kids feel tired when they travel to Saco or Hinsdale to practice. But these kids know how to flip the switch. I think it’s made them mentally tough to grind day in and day out through the season.”

Building co-ops with traditional rivals is a theme that runs through Class C. To the west of Saco on the Hi-Line there’s the Kremlin-Gildford North Stars and, farther west, the Chester-Joplin-Inverness Hawks. To the south, Grass Range co-ops with nearby Winnett, and Roy joins Winifred as the co-op Outlaws. The Denton-Stanford-Geyser-Geraldine Bearcats draw from rural schools across the Judith Basin.

“There’s no trick to making players from different schools click as a team,” says Erickson. “It’s work, and it starts in the off-season, doing things outside of basketball, getting to know each other as individuals. Then, having players accept their roles on the team, and finally having common goals that we believe and achieve together.”

Similarly, Erickson might just as well have been describing the way in which individuals join to create families that gather into communities, and the way communities come together to build schools and teams and traditions.

She laughs at the comparison.

“Yeah, our teams are pretty good reflections of our towns, right down to our goals,” she says. “We all want to be one of the eight teams that are still playing in mid-March. Every year.”

Andrew McKean writes about hunting, conservation, and wildlife management from his home in Glasgow, Montana. The former editor in chief of Outdoor Life magazine and the current hunting editor, McKean is the author of How To Hunt Everything. He also contributes to a number of national publications.

No Comments