05 Aug The Myth of the West

“EVERYONE IN THE WORLD KNOWS WHAT a cowboy is,” says Nikki Todd of Visions West Contemporary in Bozeman, Montana. “You watch people come in the gallery and see his work, and they’re immediately drawn to that iconic imagery.”

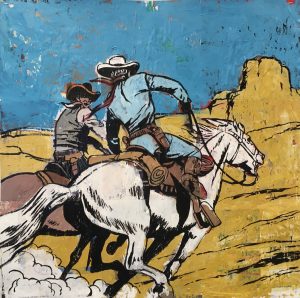

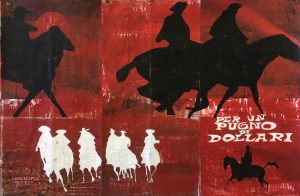

Faster Silver | Acrylic on Collage | 31.5 x 31.5 inches

The work she’s referring to is that of Gordon McConnell, a longtime Montana-based artist and curator whose portrayals of this archetypal figure speak directly to the world’s preoccupation with the American West, and how the narrative of the cowboy looms large in our national psyche. “When I was 7 or 8, we got our first TV, and it was dominated by Westerns,” McConnell says. “We were living in the West, I had all these toy figures, and every figure had a gun. It was all about the gunfighter nation. … To have so much entertainment and play activity constructed around this violent narrative, and the mass popularity of that too, I’ve internalized that; it’s something that I’ve been preoccupied with all my life.”

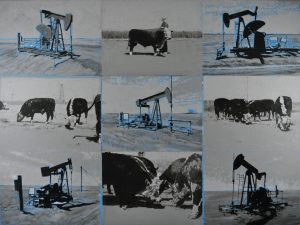

Gray County | Acrylic on Canvas | 36 x 48 inches

Preoccupied with, yes, but also inspired by. To be an aficionado of Western films is one thing; to dissect, interrogate, analyze, and abstract the genre is another entirely. “I began photographing the television screen in the ‘70s … and I began to draw and paint those images in the early ‘80s, beginning with colored pencils, ink, and oil pastels,” McConnell recalls.

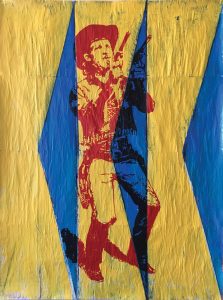

Cowboy: Space of time | Acrylic on canvas | 24 x 18 inches

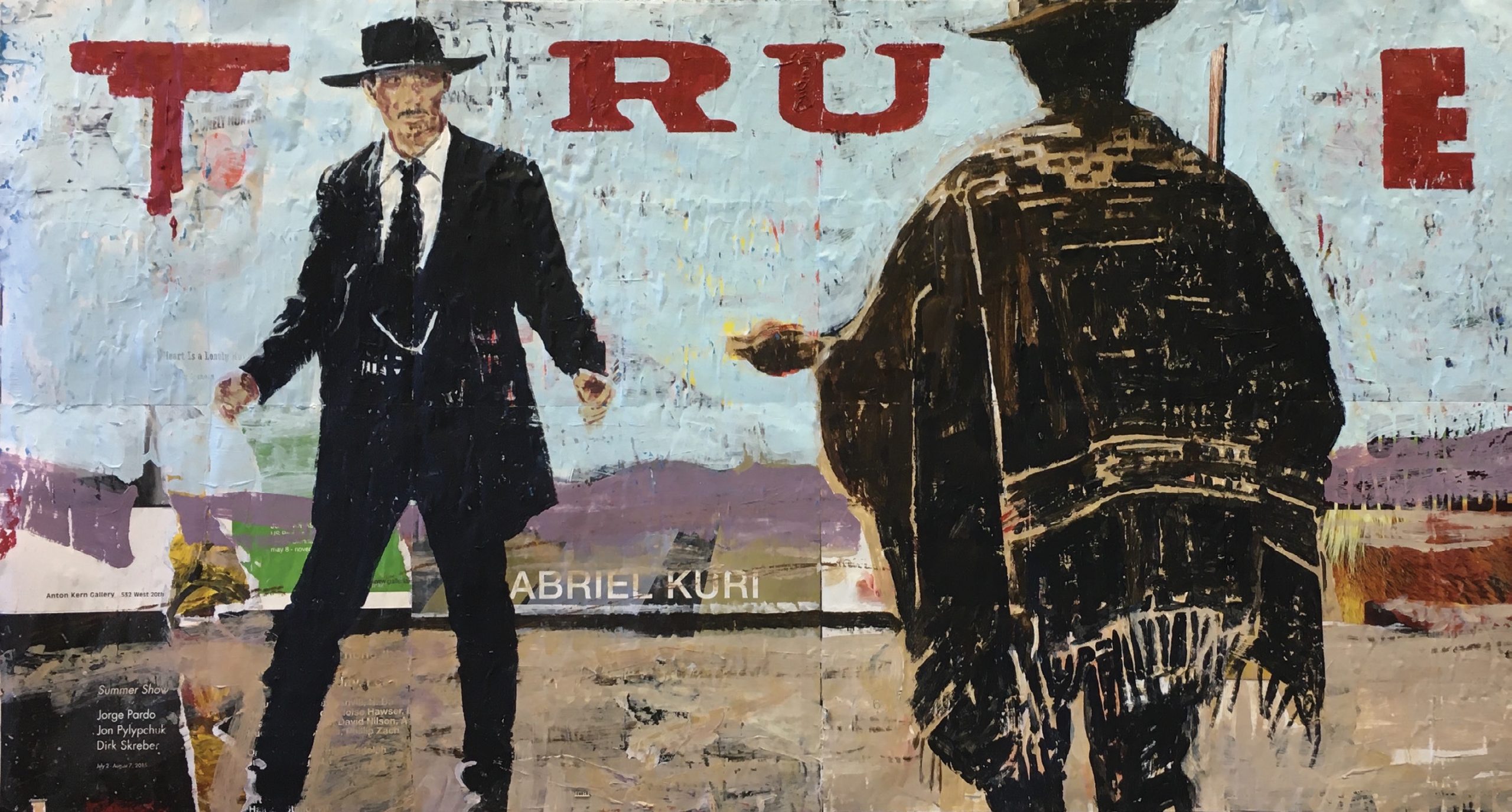

His renderings were quick and expressionistic, capturing the happenstance moment of action. Then, after arriving in Montana in 1982, he began focusing specifically on cowboys. “Consciously or unconsciously, I wanted to make work that fit somewhere on the spectrum between Modern and avant-garde art and the traditionalist art of the West; work that would be accessible and relevant on multiple levels.” Drawing on those early techniques and impulses, McConnell borrows from films and freezes split-second moments of drama, gesture, and tension in high-contrast black-and-white renderings.

The Last Cowboy : Rearview Mirror | Acrylic on canvas, mounted on wood | 11 x 25.5 inches

“There’s something about his work,” says Todd. “He’s got this motion or dynamic sort of play. It almost has a velocity to it.” By capturing that velocity — a rider on horseback, a runaway stagecoach, the breathless moment before a duel — in paint and canvas, McConnell asks the viewer to absorb and mull over the composition that would otherwise have come and gone in the blink of an eye. As a consequence, we become aware not only of the beauty of the moment, but also of the multiple layers of meaning within the frame: the storyline of the film from which the image was drawn, the more complex narratives about the mythological American West, and the multi-layered origins of the imagery itself.

Trick Shooter | Acrylic and charcoal on collage | 42 x 31.5 inches

When McConnell initially started painting images from Westerns, he recalls “consciously thinking of the legacy of Western art — Charlie Russell or Frederick Remington — that directly inspired filmmakers. And that loop-like relationship of the original painting of an early 20th-century painter, the film of a mid-20th-century filmmaker, and my paintings in a Post-Modernist world.”

Rendezvous with Destiny 2 | Acrylic on canvas panel | 7.5 x 14 inches

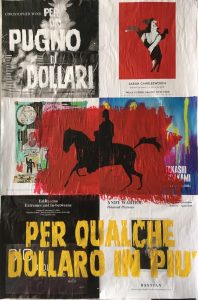

Delving even further into the past, he reminds us that the directors of classic spaghetti Westerns — Sergio Leone, for example — were well-versed in the rich history of Italian art, and applied that knowledge to their treatment of the American West. “Part of my enthusiasm for the Italian Westerns is my enthusiasm for Italian Renaissance art. It comes from my experience as an art history student and being a teaching assistant in Florence for a summer. I got the chance to see those great works and to contemplate the civic dimension of art, civic and religious, the ostentatious display, and the dignity of humanity as it was portrayed in that period.”

To draw a direct line from a film like “The Good, The Bad and The Ugly” back to the Italian masters is to elevate the Western. And McConnell’s work, by pausing and re-rendering, allows us to see how appropriate that elevation is.

Crossroads | Acrylic on collage | 21 x 31.5 inches

All these years later, McConnell’s dedication to the subject matter remains, although he admits that he struggles a bit with how complicated — and problematic — the narrative of the American West really is. After spending several recent years painting darker motifs inspired in part by the death of his parents, and in part by the state of the world, he’s finding himself pulled in new directions. “I’m beginning to not want to paint guns. I’m kind of in personal turmoil about it right now,” he says. “I’m not an iconoclast, but I am critical in my enthusiasm for this. I can’t help it. But then I have this compartmentalized part of me that still loves Henry Fonda and Charles Bronson fighting their final duel in ‘Once Upon a Time in the West.’ I just love that, it’s so beautifully done. There’s such a monumentality there.”

Gunpoint | Acrylic on canvas | 30 x 40 inches

Perhaps that friction, that internal conflict, is what has driven McConnell’s work all along, and what makes it so compelling to the viewer: The image of the cowboy resonates with many of us, gets our blood pumping, speaks to the story of Manifest Destiny that is so deeply ingrained in the American psyche. But we also know, as does McConnell, how problematic and fictionalized that story is, how incomplete.

Rider | Acrylic on collage | 31.5 x 21 inches

McConnell’s work, luckily, makes room for all of this. Like the Italian masters, he distills these complexities into narrative images, portraying the cowboy as flawed, beautiful, and entirely human.

No Comments