29 Sep The Montana Memory Project

It was called the Great American Cattle Drive, and as Sharon Moore remembers it, 300 head of longhorn out of Fort Worth, Texas, traversed more than 1,400 miles across six states to arrive six months later to her hometown of Miles City, Montana. It was epic, and all the more so because it occurred in 1995 during a cowboy-led re-enactment of the cattle drives that were commonplace throughout the West in the late 1800s. Visitors came to see the modern-day spectacle, including photographers from national newspapers like The New York Times, but mostly, it was smaller, local publications like the Miles City Star, that welcomed the herd that September.

Across Montana, memories such as this have been preserved in photographs and various publications, yet what about the actual print images and negatives which preceded today’s digital standard and are especially vulnerable if not stored correctly? Or the newspapers in which they appeared? Fearing they’d be lost, Moore discovered a way to ensure the memories of the cattle drive would live on in perpetuity, along with those from other residents with tales to tell. She stored her memories with the Montana Memory Project (MMP).

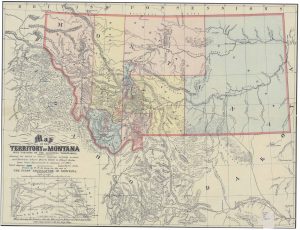

This map of Montana Territory is stored in the Montana Memory Project (MMP) database. The pink regions indicate where quartz lodes (gold and silver) had been discovered by January 1, 1865.

Moore, who works at the Miles City Star and serves on the board of the town’s Range Riders Museum, kept in touch with the newspaper’s former photographer Lara Hartley, who had been on staff during the cattle drive. And when Moore heard about MMP during a grant writing class, she enlisted their help, along with Hartley’s, in preserving the Star’s trove of cattle-drive materials.

MMP’s mission is to encourage and facilitate the preservation of “historic and contemporary resources reflecting Montana’s rich cultural heritage, and to make them freely available for lifelong learning.” Their searchable and ever-growing website, mtmemory.org, features photographs, but also print materials, such as yearbooks, newspapers, artwork, and maps, as well as visual and audio recordings.

MMP began as a pilot project of the Montana State Library, explains Jennifer Birnel, who was a middle school teacher before becoming the organization’s first full-time director in 2013. It all started about 15 years ago when Bruce Newell, the Montana State Library commissioner, pushed for the creation of a program to help libraries statewide collect and preserve the history and culture of their communities.

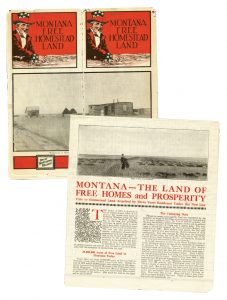

This 1912 pamphlet advertised free homestead land in Montana. At that time, American citizens with three years of U.S. residency under their belts qualified for up to 320 acres of the state’s 20 million available acres.

The Montana Historical Society was an early partner, according to their research center director, Molly Kruckenberg, and it provided administrative and financial support. To date, the society has uploaded more than 291,000 images. “Our collections on the Montana Memory Project include everything from diaries of Montanans that served in the Civil War to livestock brand registrations to Montana State Prison records,” Kruckenberg says. “Other highlights include more than 5,000 historic photographs, military enlistment cards from World War I and World War II, and county history books.”

Once organizers had established a firm foundation of interest for what would become the MMP, the next step was developing and testing logistics, says Birnel, describing the vast amounts of content that must be digitized, made searchable, maintained, and updated. The end result includes two distinct components to the MMP’s content-driven efforts: end-users and contributors, and making the site more user-friendly is an ongoing process.

A herd of 300 longhorns traveled from Texas to Miles City, Montana, during the Great American Cattle Drive in 1995, a cowboy-led re-enactment that represented those that were typical in the late 1800s. Lara Hartley, a photographer for the Miles City Star, and reporter Marla Prell tagged along to document the excursion from Sheridan, Wyoming, to Miles City. These photographs and articles are now stored with the MMP.

As the content evolves and MMP grows, so has its technology requirements. “The metadata, or the information that describes each item, is continually being improved to make the content easier to search,” says Birnel. While typed documents can be run through an optical character recognition process — which saves the content and also makes every word of the document searchable — audio and handwritten files have to be painstakingly transcribed.

Although they used to loan out scanner kits, many contributors are able to upload files on their own, such as the Range Rider Museum, which used some of the grant money available from the state library to do so.

MMP has also developed activities to engage the general public, including such things as searching family histories, exploring online exhibitions, and turning historical content into social media-worthy memes. They boosted the availability of the Museum of the Rockies’ posting of the Marlene Saccoccia Quilt Heritage Project by including a printable quilt pattern coloring book, and they frequently mine the archives for things of interest to modern-day Montanans, such as cookbooks and recipes that date back to the 1800s.

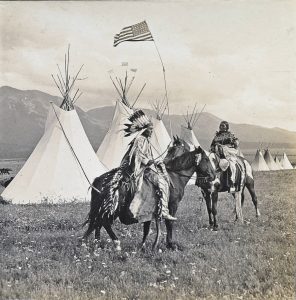

This image of Duncan McDonald [1849–1937], a tribal leader of the Flathead Indians of Western Montana, and his wife is estimated to be from around 1911, and it’s one of hundreds of original stereographs produced by Butte-area photographer Norman A. Forsyth.

Artists, writers, and plain-old curiosity seekers are among the 195,222 users worldwide who accessed MMP’s site in July 2020 alone. That figure represents 9 percent more page visits than the prior month and nearly 40 percent more than the previous year.

MMP continues to amplify and track its social media presence. More than 8,500 people were engaged in MMP’s “MEME-ory” contest, for example, in which the top meme creators won gifts from sponsors. Other popular posts include memories of a 1955 snowstorm in Lewistown that was deemed the worst ever, a photo of screen actress Myrna Loy at her parents’ home in Radersburg, and images of the first tour busses to cross a snowy Logan Pass and loggers eating lunch in Woodworth.

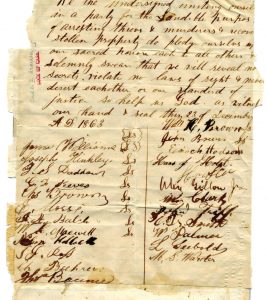

Twenty-four people signed this document on December 23, 1863, swearing their allegiance to the Virginia City vigilantes.

The statistics are part of Montana’s state tracking systems, and they provide a comprehensive analysis of how users are connecting with the site, most of whom are in the U. S. Yet fans of Montana history also exist elsewhere: Users in Canada, Germany, Australia, India, and even Russia make up the page-view count.

On the flipside, contributors are also a significant part of the organization’s focus, says Birnel, who in a typical year gives presentations to the Montana History Conference, the Museums Association of Montana Conference, the Educator Conference, and the Montana Library Association Conference, along with others as requested.

Currently, MMP has 80 contributing sites, including museums, archives, libraries, nonprofits, government agencies, historical societies, and philanthropic organizations, among others. Contributions are searchable in list and map form for organizations that range from the Beaverhead County Museum and Big Sandy High School library, to the Upper Swan Valley Historical Society and Yellowstone Art Museum. And of Montana’s 56 counties, all but 15 are represented in the project, says Birnel, who is working to bring the outliers on board.

Troops from Fort Keogh, an Army post located near today’s Miles City, take a break during an ice-cutting mission on the Yellowstone River in the middle of winter.

Montana’s rich and diverse population of Native American tribes is another focal point, says Birnel, who continues to reach out to tribal communities to engage them as both users and contributors. Currently, there are 12 collections, such as the Chippewa Cree Tribe’s Water Rights Settlement Records from the Rocky Boy area. However, most of the stories and photos are from a non-Native perspective, such as the Natives of Montana Archival Project from the Bureau of Indian Affairs.

Although the current parameters only allow for organizations to contribute, says Birnel, they would like to create the means for individuals to add content in the near future. In the meantime, the collection continues to evolve, albeit more slowly since the onset of the pandemic. They currently have 181 collections in the MMP: 120 in print materials, 52 collections of photographs, and 9 collections of audio files. That’s more than 840,000 pages of content.

Initially, says Birnel, content areas were based on what they received, all of which goes through a screening process to ensure it’s a good fit for MMP. One consideration is copyright, which applies to published and unpublished works, affording particular protection to literary, dramatic, musical, artistic, and similar creative items. “If the copyright is not an issue, we can be very creative in the types of content we share,” says Birnel. “We started with books, documents, and newspapers because they were the easiest to prove copyright in many cases.” They’ve since added photos, and audio and video files. “If the content is free of copyright restrictions and tells a story that is important to the history, culture, or understanding of Montana, then we are interested in receiving an application,” she adds.

Road construction during the settlement of Montana was no easy task.

Moore and other Range Riders Museum volunteers are hoping to add Miles City-area content to MMP’s collection soon. They’re currently working through 15 to 20 boxes of museum images from the 1800s onward, which include depictions of early bridge-builders, sheepherders, Fort Keough soldiers, and Northern Cheyenne families, as well as moments in time, such as the aftermath of the winter of 1886-1887, also known as the “big die-up” for its devastating impact on livestock.

And for them, there’s a sense of urgency to their efforts. “It’s nice when you have people who are still alive who can help clarify information,” says Moore, who is trying to fill in the descriptive content that will become part of the collection’s metadata, yet she admits some of the details have been hard to unearth. “But at least the photos aren’t lost,” she says.

No Comments