30 Jan The Missouri Nobody Knows

June 10, 1805, was another busy day for the Lewis and Clark expedition. Camped near the mouth of the Marias River, they finished caching a large supply of gunpowder, lead, and other essential goods in anticipation of returning from the Pacific by the same route. Though Meriwether Lewis and Sacagawea were both recovering from some form of dysentery, Lewis was still able to lead a crew up the Marias, where they killed and butchered four elk.

Spectacular rock formations in the White Cliffs segment of the Missouri inspired Captain Meriwether Lewis to pen particularly poetic descriptions in his journal.

Meanwhile, Private Silas Goodrich went fishing, as he did at nearly every opportunity. That day’s catch included two of the 12 fish species first described for Western science during the expedition. Lewis (the more astute naturalist of the two captains) described the first as “…precisely the form and about the size of the well-known fish called the Hickory Shad or Old wife.” Biologists eventually identified this fish as our goldeye, Hiodon alosoides. He reported the second as “…about 9 inches long, of white color, round, and in form and fins resembling the white chub common to the Potomac.” Scholars later concluded that this was the sauger, Stizostedion canadense.

Both are among the surprisingly small number of today’s Montana game fish that are true natives of the region (more on this paradox to follow). Despite the recent explosion of interest in Montana fly fishing, both species remain virtually unknown among fly-rod anglers, save for a few eager to fish outside the proverbial box. For us, the remote segment of the Missouri River between Great Falls and Fort Peck Lake is a great place to do so amid spectacular scenery, rich historical context, and solitude — an ambiance that has become increasingly difficult to find on Montana’s most popular trout streams.

Over 215 years after Goodrich enjoyed his scientifically productive angling interlude, my wife, Lori, and I spent a pleasant summer evening with another couple, camped beside our inflatable raft on the left bank of the Wild and Scenic Missouri River. The summer solstice was almost upon us, but deep in the river bottom, the still air was cool enough to make me reach for a wool shirt as soon as I crawled out of my sleeping bag the following morning. I thought about doing my wife and friends a favor by making coffee, but the lure of the river proved too strong to ignore.

This stretch of the Missouri is all Class 1 floating, making it ideal for beginners. Photo by ROLAND TAYLOR

The surface of the water near the current line was alive with feeding fish. Had I spotted this activity upstream, below Holter Dam, I’d be trying to figure out how to match the insect hatch, but I faced no such challenge here. These fish weren’t selective trout. They were goldeyes, and I was standing near the site of Lewis’ first description of the species.

Most warm-water game fish are sub-surface feeders best targeted with streamers when fishing with flies. Goldeyes are a welcome exception for dry-fly enthusiasts, and they jump acrobatically when hooked, two characteristics that help compensate for their small size and poor table quality. They can be a lot of fun on light fly-rod tackle. Anticipating just what I saw in front of camp, I had brought along a four-weight rod loaded with a floating line, hardly appropriate tackle for the walleye and northern pike that were my primary quarry. By the time I had the little rod rigged for action, I could hear camp starting to stir behind me. Ignoring the temptation of breakfast, I began to cast a generic dry fly onto the slack water between the current and shore. Two casts later, I watched muted sunlight flash from the silvery sides of an energetic foot-long fish that really did look like a shad, just as Lewis had suggested. Where were the screaming reels and rods bent double that seem to have become a necessary component of fly-fishing stories? I didn’t know, but they weren’t there with me on the banks of the Missouri. I didn’t miss them. I was too busy enjoying the scenery, history, and solitude … and having fun. The Upper Missouri River Breaks National Monument runs roughly 150 river miles downstream from Fort Benton to the Charles M. Russell National Wildlife Refuge, near the Fred Robinson Bridge on U.S. Highway 191. Canoes are ideal for exploring the Wild and Scenic Missouri, as they are capable of getting you downstream faster than rafts or drift boats if you need to hurry. Photo by ROLAND TAYLOR Created by proclamation in 2001 during the Clinton administration, it did not arrive without controversy. Local ranchers were outspoken about their concerns that monument status might impact grazing leases and access to private property. Fortunately for all, none of that has come to pass. Most of the terrain along the river is a patchwork of public land overseen by the Bureau of Land Management (BLM), U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service, and the state. It also includes scattered private inholdings, which require landowner permission to access. GPS and excellent maps from the BLM office in Lewistown make identifying these boundaries easy. Federal legislation passed in 1968 granted Wild and Scenic status to the Missouri between Fort Benton and the Fred Robinson Bridge.

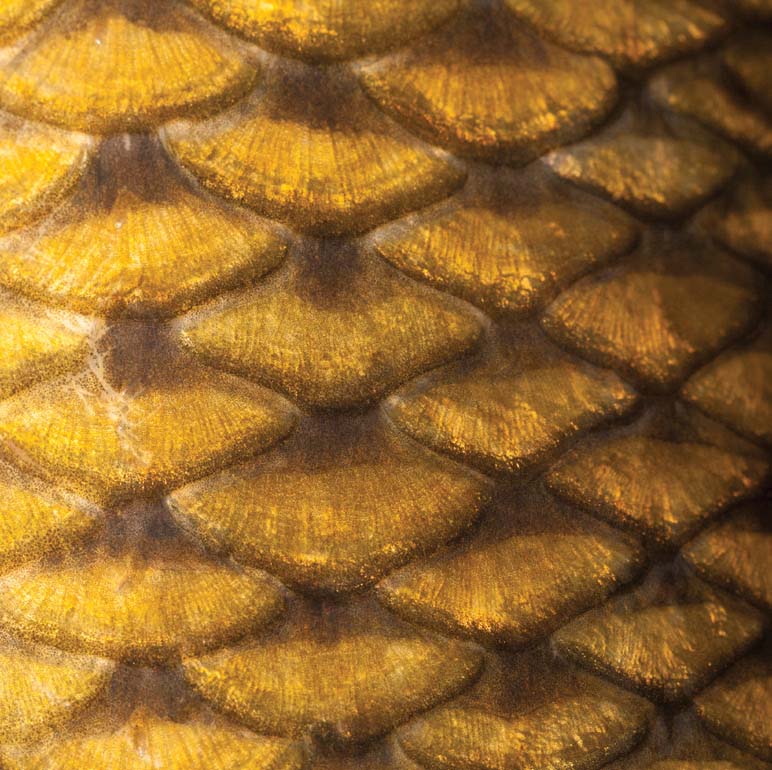

For recreationists, the most significant aspect of this designation is seasonal closure to motorized boats in specific segments of the river, details of which are also available from the BLM. These rules are much less complicated than they first seem, and the effect allows summer floaters to enjoy the river in quiet and solitude. Few visiting anglers have ever heard of goldeye, but they strike flies readily and are lots of fun on light tackle. Photo by Jeremie Hollman While I’ve seen it all from Fort Benton to Highway 191 and beyond, my favorite stretch is the river’s upper end. In many places, the best and only way to experience it is by floating — launching at Coal Banks Landing east of Fort Benton and taking out 41 river miles later at the PN Bridge north of Winifred. You can make the trip in two days if you are in a hurry, but I prefer to spend three nights camping on the river. Anglers are learning how to catch carp on flies. The golden-brown scaled non-native species have become popular because of their size, which can reach over 30 pounds. Photo by Jeremie Hollman Although some areas are identified as “rapids” on maps, that term dates back to the steamboat days. This entire stretch of river is easy Class I water that’s ideal for beginners. Some make the float in kayaks, which are available for rent in Fort Benton. Canoes are probably the best choice, representing a compromise between maneuverability and load capacity. I’ve made several trips in inflatable rafts, which allow plenty of room for gear and provide an excellent casting platform. An upstream breeze can slow a raft down considerably, so if you choose that option, it’s best to plan for an extra day on the river. The designation “Upper” Missouri Breaks can be deceiving. Upstream, near the town of Craig, Holter Dam has created a spectacular tailwater fishery with all the characteristics of the famous western Montana streams to which visiting anglers flock every summer: clear water, complex insect hatches, tourist facilities, and large brown and rainbow trout. From that perspective, the river downstream from Great Falls looks more lower than upper. Seasonally, there are a few trout in the Wild and Scenic segment, but it is predominantly a warm-water fishery, offering species most fly-rod anglers ignore: northern pike, walleye, and sauger. I have seldom seen anyone else fly fishing there. In addition to solitude and scenery, one of the pleasures of casting a streamer in the Wild and Scenic Missouri is never knowing what might hit it next. Broad and gentle, the Wild and Scenic Missouri offers technically easy floating. The “rapids” referred to on maps really aren’t: The term is leftover from the steamboat days. Photo by Roland Taylor After getting off to a late start on that same trip, we camped in what is likely the most scenic area on the float: the White Cliffs. When the outbound expedition reached them in late May of 1805, Lewis’ journal entry sounded even more awestruck than usual when he wrote, “The hills and river cliffs we passed today exhibit a most romantic appearance … so perfect indeed are those walls that I could have thought that nature had attempted here to rival the human art of masonry had I not recollected that she had first began her work.” A leisurely hour after we launched, we pulled over to the river right for a streamside brunch. My decision to ignore the meal and go fishing didn’t surprise any of my companions. Rigged for bigger fish than goldeye, I was casting a large streamer with a six-weight rod and sink-tip line when I received a hard strike. I had no idea what the fish was until I worked it to the bank and found myself confronting a channel catfish. I shouldn’t have been surprised when I learned later that the channel cat was yet another first of species by Goodrich — the expedition’s acknowledged fishing fanatic — this time recorded by William Clark in July of 1804 in what is now South Dakota. The large catfish species native to North America are all popular among conventional tackle anglers fishing with bait, but only the channel cat will readily take artificial lures and flies. I frequently caught them on flies in the Poplar River when I lived in the northeastern corner of Montana. A prized game fish, smallmouth bass are abundant in Fort Peck Lake. Occasionally, some move upstream into the Missouri. Photo by Jeremie Hollman Neither goldeye nor catfish are widely accepted as fly-rod game fish, but I broke out of outlier mode later that evening. When our group finished dinner (which included fried catfish), I decided to take advantage of the long summer twilight by squeezing in another hour of fishing. Below the towering cliffs, shadows had already started to fall when my bright, gaudy streamer received a strike out in the current. The first strong run convinced me that the fish was a northern pike, and a big one at that. Pike are notorious for cutting through standard monofilament leader material with their sharp teeth (braided wire is the preferred alternative), but the fish and I stayed attached. Pike strike hard and are usually good for one strong run, but they lack endurance. When I brought this one to the shore five minutes later, I saw that the streamer was hooked on the outside of the lip, beyond the reach of its teeth. Lucky me. We live in a state obsessed with trout, and I get it. However, I’ve always been a fan of taking the road less traveled, which probably explains my lifelong interest in fly fishing for offbeat fish. Montana waters are home to a smorgasbord of warm-water game fish that fly-rod anglers largely ignore. Most are introduced species, which sounds better than alien invasive species, although, biologically, the terms mean the same thing; so, too, are the brown and rainbow trout that make Montana fishing famous. Our judgments can be highly arbitrary: When the non-native species are pheasants or Hungarian partridge, we welcome them, and when they’re knapweed or leafy spurge, we don’t. Northern pike are likely the most abundant game fish in this stretch of the Missouri and are certainly the easiest to catch on a fly. Their sharp teeth can easily cut through a leader unless the angler uses a wire trace just above the fly. Photo by Jeremie Hollman My enthusiasm for bass, pike, walleye, and the like is a great excuse to visit wild places I might never see otherwise. The Wild and Scenic section of the Missouri River is a great example. Would I make that float trip if I couldn’t fish along the way? Probably not. The years I spent living in Alaska taught me to appreciate the value of wilderness solitude for its own sake, and I miss it. The “Upper Missouri” isn’t the North Slope of the Brooks Range, but it’s about as close as one can get in the Lower 48. Absent my fly rod and affection for fish beneath the dignity of most fly fishers, I likely wouldn’t have had a chance to retrace the steps of Lewis and Clark. What a loss that would have been. A central Montana resident since 1973, E. Donnall Thomas Jr. has been everything from a physician to a bear hunting guide in Alaska. He writes about the outdoors for numerous publications and lives in Lewistown, Montana with his wife, Lori, and their bird dogs.

No Comments